The Art Gallery of NSW’s upcoming show America: Painting A Nation is a true landmark event. Art historian Dr Chris McAuliffe, who acted as a consultant for the exhibition, says that it is nothing less than the first major retrospective of American art to be presented in this country. The show covers a breadth of American art, from the pre-revolutionary era all the way through to the 20th century. The show collects pieces from art institutions all across America and spans works from more than two centuries – the earliest comes from 1750, the latest from 1966. Viewed together as a collection, the works tell a story of a nation discovering its unique identity and character.

The earliest works in the show are portraits of society figures from the 18th century. “At that point in American history, Philadelphia was the fourth-largest city in the British Empire,” says McAuliffe. “Wealthy people and the Atlantic coast still had very strong connections to England, so the art that came out of that period was portraits of people with high social standing, commemorating occasions like marriages and graduations, and just showing off their social standing.” The funny thing about these early portraits, McAuliffe says, is that even though they are painted in an English style, the figures in them just look unmistakably American, in the forthrightness of their posture, and the confidence of their poses.

Revolutionary leader John Adams said, at the time, that it was important for American painters to shift away from an English sense of pomp and ceremony towards more American qualities like integrity and honesty, diligence and hard work – by the early 19th century, these ideals could truly be seen. “In the 1820s and 1830s, a very distinctive American romantic landscape started to emerge,” McAuliffe says of some of the works that can be seen in America: Painting A Nation. “The artists were curious about the distinctive scenes that could be found in the American landscape, and the works they produced were quite spiritual – almost religious, you might say.”

One interesting characteristic of American landscape painting, McAuliffe says, is that it takes on a spiritual, almost religious quality. “American landscape painters were interested in the idea of God as the maker of the landscape,” he says. “They would ask, ‘if I meditate on this landscape, will that bring be closer to God?’” Artists would see the divine in vistas like the Grand Canyon, an attempt to articulate creation through their works. This particular trait is what made the American landscape painting of the period so unique among the colonies. “When it comes to American landscape painters, those moments of stillness and isolation are really fulfilling – they’re contemplative and reflective.”

By the late 19th century, American art had begun to explore and examine everyday life, and some of his favourite works in the show come from this period. “There’s a beautiful painting of two young boys, one of whom has his carpentry tools out and is mending a toy boat for the other. Looking at it, you really get a sense of class relations – this is how a tradesman will engage with a businessman.” Although they might appear to depict the mundane, McAuliffe says that many works from this period are complex morality plays. “I find it very interesting the way that Americans debate values in their art,” he says. “Many pieces are reminders of how civic society can and should work.”

By the early 20th century as the World War I approached, American artists had begun turning their gaze towards Europe. “We have a painting in the exhibition by Max Weber, who had a studio in the same building as Pablo Picasso,” McAuliffe says. “There’s another artist Marsden Hartley who exhibited with Kandinsky in the Blue Rider group. The interesting difference with Americans is that they really self-consciously tried to build an avant-garde culture at that time, making connections with Europeans, having exhibitions, making their own magazines. They brought a really great energy to it. They were conscious of their own modernity.”

The exhibition concludes in the 1960s, but rather than show abstract impressionist works by Pollock and Rothko – the likes of which Australians can already see in bigger collections – America: Painting A Nation ends by returning to the poetry of the American experience. “We end with some paintings that I think are really interesting,” McAuliffe says. “There’s one by a remarkable abstract painter named Stuart Davis. He did a lot of incredible paintings of neon lights and street signs and petrol stations. He said that once you’ve seen a neon light, you’re never going to think of colour in the same way again, and he just nailed the way that everyday life constantly brings you up against these remarkable shifts in perception, and you have to come to grips with them.

“The last piece in the show is a really minimalist work by installation artist Robert Irwin,” McAuliffe says. “It’s a white disc hovering in front of the wall, and it goes back to this idea of American landscape painters reflecting on stillness and quiet. It’s interesting to end with paintings that are about those classic American qualities, moments of stillness in the landscape, but to see those qualities through the prism of city life. The show could have ended with some big, macho works by the abstract expressionists, but instead, it ends by returning to that idea of the poetic American experience – highways, neon lights …”

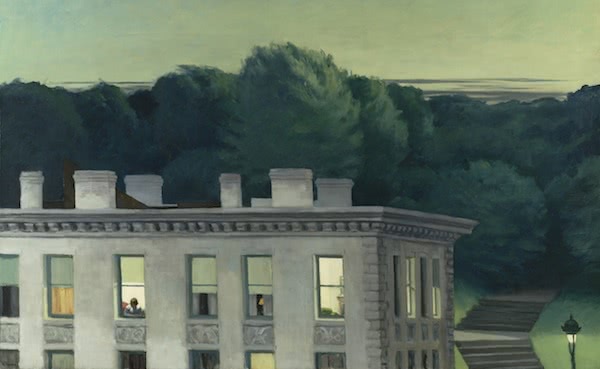

My own favourite American artist is Edward Hopper, and McAuliffe tells me that the show includes one of his works. “We have a beautiful Hopper from the early 1930s, borrowed from Virginia,” he says. “It’s a painting of an apartment building with a lonely woman visible through the window, and it has that classic Hopper sense of being lonely and contained. It’s funny,” he continues, “because I was sniffing around and the National Gallery has one Hopper, a print from the 1920s. I realised, when I was researching for this exhibition, that a lot of Australian galleries have incredible collections of post-war American art, but hardly anything prior to World War II. It will be a really good chance for people to see this work.”

BY ALASDAIR DUNCAN

*Image: Edward Hopper, House At Dusk, 1935 (detail).

America: Painting A Nation for Sydney International Art Series presents at theArt Gallery of NSW from November 9 through February 9, 2014.