Sex, drugs, rock’n’roll. It’s no secret drugs have a significant presence in the music industry. JOSEPH EARP investigates just how widespread they are in Australian music, and how music has historically dealt with the question of drug use. This article was produced in partnership with Dopamine.

“Music is fulfilling. The next day you feel better. Drugs, the next day you feel terrible – unless you have more drugs.” – Neil Young

There are certain images that have become seared onto the pop culture consciousness. Images of tortured musicians slumped over their guitars, needles sticking out from their track-mark-studded arms. Images of great rock’n’roll doyens hoovering up blow in a jacuzzi. Images of performers searching for a quick pick-me-up before they head out under the bright lights of the stage. These are images that we now know intimately, that belong almost entirely to the realm of cliché.

After all, drugs and rock’n’roll are so deeply intertwined with one another that we often talk about both when only specifically mentioning one. They mean the same things to us. They mean excess, privilege, self-destruction and wealth. They mean all the things that maybe we don’t often admit to ourselves that we want, and all the things that we know might ultimately kill us.

Many of rock’n’roll’s most mythic, legendary tales concern the imbibing of titanic amounts of illicit substances. We are obsessed with these stories; we tell them to ourselves over and over across different mediums. They’re stories about musicians succumbing to the allure of drugs and then slowly, defiantly rising back up to the top.

Indeed, we like our heroes to come pretty fucked up. That’s why we are obsessed with the chemical fortitude of Motörhead’s Lemmy, a man who once claimed years of abuse had turned his blood into a treacly, narcotic-laced sludge. That’s why we love The Beatles’ experimental years, that short period where the once fresh-faced Fab Four transformed into a semi-mystic troupe of Jodorowsky-esque astral pioneers. And that’s why we love the punky detachment of Lou Reed, that arch junkie whose work was so often composed to be enjoyed with the help of hallucinogens.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

This isn’t a contemporary endemic either, or one that began with the boomers. Lemmy, Reed and The Beatles might be the first people we think of when we think of coked-up creatives, and yet they are but children compared to the performers of the ’30s and ’40s, the whacked-out weirdos who regularly pumped themselves full of a range of illicit substances.

“Drugs have long provided popular music with one of its more ambivalent subjects,” noted the writer Andy Gill in an article for The Independent. “The image of the jolly ‘reeferman’ is a recurring figure in jazz lore, and Ella Fitzgerald’s jocular ‘Wacky Dust’ [testifies] to the properties of cocaine.”

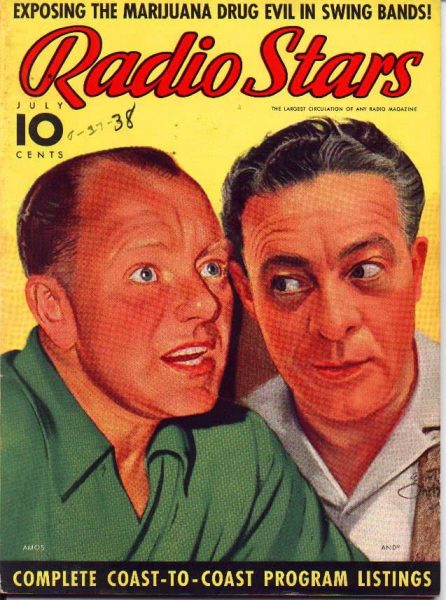

Indeed, as far back as 1938, hysterical muckrackers like Radio Stars journalist Jack Hanley were writing articles topped with fearmongering headlines such as ‘Exposing The Marijuana Drug Evil In Swing Bands’.

“One leader told me of a young man in his band who was a crackerjack musician, but who used the weed so consistently that he was quite undependable,” wrote Hanley, the moral outrage shimmering just beneath the surface of his words. “The fits of deep depression reefers so often produce would seize him until he had to be restrained from suicide.”

That’s not even to mention the fact a host of songs now considered rock’n’roll standards were initially written as paeans dedicated to the losing of one’s mind. Songs about pot defined the ’30s, a decade in which immensely popular performer Stuff Smith released the weed smoke-smothered ‘If You’re A Viper’, and the ’40s weren’t much cleaner – think boppy, seemingly bright and family-friendly tunes bursting with references to getting high and getting down.

Even ‘La Cucaracha’, that most seemingly innocent of songs (you know the one: that gleeful, leery tune we associate equally with sports chants and with Mexico) is actually about pot-smoking. “‘La Cucaracha’ crackled with life, a swaying Spanish-tune-turned-Mexican corrido quickly picked up by jazz bands and danced into popular music,” writes Margaret Moser in ‘If You’re A Viper’, her brilliant article penned for The Austin Chronicle about the history of drugs in music.

“No song better evoked the languorous image of life south of the border in vintage films, newsreels, and radio programs of the day. Yet few people realized the lyrics bespoke a cockroach’s yearning to stay high: ‘La cucaracha ya no puede caminar … por que no tiene marihuana por fumar,’ basically translates as, ‘The cockroach can no longer walk because he doesn’t have any marijuana to smoke.’”

By the time the ’50s and ’60s rolled around and the American counterculture movement strengthened and solidified, the theme of drug use took hold over pop music and rock’n’roll. Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On set the tone for all pot-laced pop epics that followed it; Charlie Parker’s An Evening At Home With Charlie Parker Sextet was a scatty, frenetic ode to heroin use; and Frankie Lymon’s The Teenagers Featuring Frankie Lymon was indebted to the drugs that would eventually claim Lymon’s life.

And from then till now, drugs and music have only become further entrenched in one another. They have only grown closer; each more indebted to the other as the years roll on.

“I think in many ways, it seems more odd now to encounter a band that doesn’t have at least one mention of drugs than it does to encounter a band that has lots of references to drugs,” one anonymous writer tells the BRAG. “It’s almost what we expect from music now.”

So, one has to ask: what has all that drug talk done to the popular consciousness? The question, for the record, is not designed to be framed in a puritanical way. It’s not a question about whether or not songs concerned with drugs have turned our children to the devil, or fried their brains, or corrupted them and their youth. It’s more a question about whether or not we can even talk about drugs in music effectively in 2017. When you can no longer separate myth, lies, fiction and reality, can you say anything with any real authority?

At this stage, given all the stories that we have told ourselves, is it possible that we have lost sight of reality, confused by larger-than-life figures and their drug habits? Have the grand characters of rock’n’roll’s history become overly mythologised, now as true to life as the characters in children’s fairy tales? And, perhaps most pressingly of all – do we even know how to talk about drugs in the music industry any more?

Writing high: how musicians use drugs to aid creativity

In 2014, Blur and Gorillaz bandleader Damon Albarn sat down with an interviewer from Q magazine and in his gentle, lilting Essex accent, methodically extolled the benefits of heroin use. “I hate talking about this because of my daughter, my family,” Albarn said. “But, for me, [heroin] was incredibly creative … A combination of [heroin] and playing really simple, beautiful, repetitive shit in Africa changed me completely as a musician. I found a sense of rhythm. I somehow managed to break out of something with my voice.”

Albarn’s working ‘method’ was to stick to five days on heroin and then take two days off, in the process developing the kind of formalised, rigid schedule he assumed would stop him from spiralling into an all-out addiction. And it really worked – or at least, so he said.

As far as Albarn was concerned, the heroin freed him up: it allowed him to think of chords and lyrics that would usually be barred from him; it pushed and it challenged him. Heroin was his muse. As one might be able to imagine, Albarn got himself into a lot of trouble over the interview – detractors from all walks of life argued he was romanticising drug use, leading his potentially young, vulnerable fans down a fraught path.

Nonetheless, although Albarn’s comments could indeed be read as dangerous, they also represent a rare example of a musician talking matter-of-factly about drugs. The one-time poster boy of Britpop wasn’t rambling about sticking a needle into his arm during a raging party, or getting fucked up in order to survive another night on a godawful tour. He was talking about drugs in the language of medication – as though there was something intrinsically casual about them, something that meant they were a mere part of his life, rather than the whole of it.

It was, in some ways, a striking change from the usual deluge of toe-curling tales about druggy extremity that have oversaturated the news cycle for years. Albarn’s heroin chat seemed more realistic; more akin to the stories of middling drug use that define the industry for so many of those who work in it. His experience was so much like the experience of those low-level musicians who enjoy lighting up a joint while writing their new record, or those who do a line or two of coke just before hitting the studio.

“Illicit drug use in Australia is often rendered as a black-and-white battleground: you’re either a drug user and thus looked down upon as a loser and a criminal, or you’re an anti-drugs totem of purity,” wrote the author Andrew McMillen in a 2014 article for The Guardian. McMillen was also behind the conversation-defining work Talking Smack: Honest Conversations About Drugs, which featured a series of interviews with prominent artists about drug use in the music industry.

“Usually the discussion is dominated by politicians, police and sensationalist media outlets who stand together in condemnation of anyone who would dare consume a drug that isn’t alcohol, caffeine, nicotine or a prescribed medication,” McMillen explained. “While working on Talking Smack I found an important distinction to be made: that despite the noisy negatives often associated with drugs at all levels of society, many of my interviewees had positive experiences. This is a rarely-acknowledged truth for many Australians, regardless of whether or not they’re employed in the creative industries.”

“I think people really love these big hotel-wrecking stories,” an anonymous musician tells the BRAG, agreeing with McMillen’s assessment. “And you can see why. Those are the stories that people make movies out of. I think that those stories are impressive, ’cause they kinda make us think our heroes are even more heroic. It’s like, ‘Shit, [Jimi] Hendrix was just fucking constantly high, how the fuck did he manage to make all that amazing music when he was so consistently messed up?’ It makes musical heroes harder to understand in a weird way, and that makes them [people] to look up to.

“But that means we don’t always talk about what I kinda think [about] as drug use in the music industry, which isn’t usually like that. I mean, it is when addiction gets too much and people start to get out of control and all that. But usually when I’m writing, I will take something – maybe a few caps, maybe smoke a joint – and then write on that. That’s more what I think of when I think about drugs.”

Certainly there are a whole host of musicians out there who seek the aid of substances in order to spark their creative fires; those who use drugs to spur on their work.

“I just [take] the good [drugs],” Australian musician Brendan Maclean jokes. “Weed, dexies… I used to take Xanax but that made me too sleepy. I suppose what I’m looking for is to get out of my daily routine. Otherwise it’s to stay awake, twist the song or just because I like being stoned. And I mean, I always follow the golden rule: write high, edit sober.”

It’s not just downers either: there are a range of drugs musicians use to help shape and sculpt their work. There are those who drop acid while writing; those, like Albarn, who come out punching from heroin’s corner; and those who use stimulants like coke and ecstasy to keep them writing fast and for hours, looking for a way to keep their limbs moving as quickly as their brains.

“I used to do coke pretty regularly,” another musician explains to the BRAG. “Just because I could do it and then I wouldn’t really have to worry about sleeping so much. It would just mean that I could churn out a lot of work over the space of a single night. Some of it was a little shitty, but also, a lot of it wasn’t. It just made everything move a lot faster.”

“Coke is good for rehearsals,” another musician reveals anonymously. “We would sometimes have a little bit when it was just the three of us, jamming around in a garage. It just means you can get through a lot more, and a lot faster. I suppose it is a bit dangerous, because it can mean you drink more, or maybe lose focus a little bit. But we always found that if we kept on top of it [and] didn’t get too fucked up, it never once was a problem.”

I always follow the golden rule: write high, edit sober.

Such creative experiences are actually backed up – at least in part – by science. The creative urge can indeed be influenced and altered by a range of drugs, with the neurologist Dr. Alain Dagher noting in an interview with Vice that drugs can “mak[e] conceptual links in your brain between things that you may not normally link”.

“The most obvious example of the way a drug can help creativity is that most of us are, for the most part, inhibited in many ways,” Dagher said. “Many drugs, especially in small doses, can relieve that inhibition. Part of creativity is being original. So drugs like cocaine, and perhaps heroin, have that ability to make you have original thoughts.”

“What [drugs do] is lower your judgement,” said Harvard neurologist Dr. Alice Flaherty in 2014. “You [just] think what you’re writing is more creative. It reminds me a little of William Stafford, who said that all you have to do to get rid of writer’s block is just lower your standards.”

Of course, relying on drugs in order to write has an array of sometimes life-threatening downsides, and remains a dangerously unsustainable long-term method. For a start, believing that simply maintaining a heroin habit will transform you into the next Damon Albarn or Kurt Cobain is the kind of broken reasoning that accounts for a lot of bad bands – and a lot of even worse drug problems.

As Dagher himself pointed out, drugs aren’t the creative be-all and end-all, no matter how seductive they might be. “The other thing about creativity is that it’s not just about being disinhibited,” he said. “And it’s not just forming associations – you have to have a certain amount of talent. You need to not just have ideas, but know what are the good ideas and what are the bad ideas.”

And that is the common criticism raised by those who see drugs as little more than an expensive, time-consuming crutch; a prodding of creative talents rather than a guaranteed artistic kick up the bum.

“I don’t think it’s very helpful to adopt this attitude that is like, ‘Oh, the only way I can write is on drugs,’” says an unnamed artist. “Maybe just like, occasionally using it to flip things on their heads a bit is cool, but to be honest, most of the time ‘drug writing’ is the kind of stuff you could have just done when you are sober anyway. I think people sometimes try to justify their drug use with their art, which is a bit shitty.”

Elefant Traks label manager and rapper Urthboy agrees. “I’ve never really had any clear proof [that drug use helps creativity],” he told McMillen for The Guardian. “You can’t say that’s a fact when you write really good stuff without smoking. To ever suggest that weed is an essential ingredient in that process is almost to give up on your own abilities.”

One industry player the BRAG spoke to put it even more simply. “It’s kinda fucked to assume that The Who were only The Who because of drugs, or that Pink Floyd was only Pink Floyd because they liked to get fucked up. Then you’re saying that it all it takes to make great music is a lot of money and a good drug dealer. In which case, there’d be a lot more great music out there, that’s for sure.”

Performance enhancement: Aussie musicians share stories of drugs on the road

In 1976, iconic American group The Band took to the stage for the very last time. The five-piece went all out for their farewell concert, providing the entire audience with an extravagant turkey dinner to chow down on before the show started, recruiting beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti to get the fans warmed up with some rhymes, roping in a bunch of guest stars to join them onstage for some of their classic songs and hiring a young cinematic maverick named Martin Scorsese to film the proceedings. They called the bonanza The Last Waltz, and did everything they could to make sure it went ahead without a hitch.

Which, credit to them, it pretty much did. Notwithstanding the typically snotty stage presence of one Bob Dylan, and a little bit of drunken, boorish behaviour from a few members of the audience before the show started, The Last Waltz was a famously brilliant gig marred only by a large lump of cocaine hanging out of guest performer Neil Young’s nose.

See, the ‘Helpless’ singer had treated himself to a little bit of a backstage energy boost, ploughing snout deep into some blow to help him power through his brief appearance onstage. Only thing is, he’d forgotten to wipe his nose afterwards, and the dangling nugget of coke was plainly obvious to everyone in the front row – and, perhaps more disastrously, to the watchful lenses of Scorsese’s cameramen. In fact, Scorsese was later strong-armed into editing the now-infamous cocaine booger out of Young’s nose for the cinematic release of the film.

Needless to say, Young was not the first musician to use a chemical aid in order to get through a performance, and he won’t be the last. For some musicians, uppers are as important to the touring life as downers and hallucinogens are to the writing of their music.

“I think that really is the biggest way that I personally use drugs,” says one artist. “[Taking drugs] really becomes something that you sort of feel like you have to do after days and days on the road. When you’re touring for really long stretches of time, it becomes harder and harder to play shows – you get over alcohol, you get over your friends, you get a little bit over yourself… drugs help with all that.”

Cocaine, caps and heroin tend to be the most common stimulants that accompany performers on the road in Australia. The triumvirate of intoxicants all share endurance-strengthening properties, at least in small doses: they help you push yourself further, play faster, be more present.

“You see things that you wouldn’t ordinarily see if you have taken something before a show,” one musician explains to the BRAG. “The whole experience is different for you. Maybe it is what the audience sees when they look at you – they get that buzz and that high that you get when you do drugs.”

So alluring are drugs for touring musicians that one artist interviewed for this article says the local Australian punk scene has a widespread heroin problem. He describes hard drug use as being more common than people might think – rather than being the kind of substance people only dabble in when pressured by friends, or after a few too many drinks, he suggests that heroin is integral to the scene and the touring capabilities of its members. “It really becomes the kind of thing that people rely on,” he says. “For some musicians, they really can’t perform without it.”

It is hard to ascertain whether such a bold claim is exaggerated – for obvious reasons, it is difficult to find knowledgeable sources who are actually willing to be named, or speak on the record in any level of detail – but there are others willing to back up the same story. Indeed, another anonymous industry member reveals that such a severe level of drug use is often facilitated by labels, event managers and those who run festivals.

“I was at a reasonably big Australian festival and all these minders came around and offered drugs,” the BRAG is told. “They were coming around with all these hash brownies being like, ‘Who wants some?’ Then, a little later they were taking around a hat so people could pool in and all buy a little bit of coke together. That stuff is pretty normal, actually. There are people who are paid to keep musicians happy. And sometimes what keeps musicians happy is drugs.”

They were taking around a hat so people could pool in and all buy a little bit of coke together. That stuff is pretty normal, actually.

In the aftermath of digging up such drug stories, one is left feeling a little bit hopeless. People are not keen to talk about chemical abuse when they are even peripherally associated with the public eye – most of the musicians quoted anonymously in this article had to have their arms very much twisted, and even then they sometimes succumbed to vague clichés and half-baked details so as to ensure their tales would not incriminate them. “Pretty much whatever I tell you, someone is going to be able to recognise me from it,” one of the sources says. “And that would majorly suck.”

What are we left with, then, but a collection of rumours that people already may well have guessed at – anonymously confirmed stories that indicate yes, the life of a musician is filled with substance abuse and wild parties and all sorts of illicit pick-me-ups designed to get them through the rigours of the tour? And what good does learning that kind of stuff do?

The answer, though not immediately apparent, is that such stories, no matter how vague, do help get us incrementally closer not only to the truth, but also to a place where the truth might be more openly discussed. Every time we try to talk about drugs the way we would talk about any other consumable – the way we talk about food, the way we talk about clothes – we get a little bit nearer to a kind of acceptance.

And this is the only thing that will help us understand drugs; the thing that will help us either work to eliminate the ravages inflicted by its addiction, or to help people use illicit substances in beneficial rather than damaging ways.

“Drugs aren’t one way,” a final musician tells the BRAG when asked to contribute to this article. “You shouldn’t write about them in a way that makes them seem like they are.”

And they are right. As much as we might like to pigeonhole substances as inherently good or brutal, they are inherently neither. Drugs in the music industry are multi-faceted and multi-dimensional; ever-changing beasts that mean a thousand different things to a thousand different people.

But they’re definitely there, and probably closer than you think.

This article was produced in collaboration with Dopamine.