Toput me to sleep as a child my grandmother would read to me whatever Agatha Christie novel she happened to be enjoying at the time. So it was that my earliest memories are of the murder of Roger Ackroyd, of a mysterious house at Styles and, of course, a Belgian detective brought to inimitable life by David Suchet over the course of 25 years. Though his latest character inThe Last Confessionis far removed from the world of Hercule Poirot, Suchet is thrilled that after all this time, his “little friend” is alive and well across the globe.

“I have a little story for you,” Suchet says over coffee. His voice is colourful and pronounced; exactly what you would expect for someone who honed his vocation in repertory theatre and The Royal Shakespeare Company. “I was in Los Angeles for The Last Confession, and a family contacted me. They asked would I mind if I met them afterwards. I came out to the stage door, and there was this young boy of 13 dressed as Hercule Poirot, with the full costume and moustache. The wing collar, bow tie, waistcoat. His parents told me that he had insisted he fly from LA with them to New York, because he couldn’t find the right homburg hat. And that’s today! To witness that young boy who sat through the play, all dressed up as Poirot and not at all embarrassed, is so gratifying and humbling. I was offered very suddenly to play this little man back in 1987, which changed my life, and I am finding out as I travel now, has changed the lives of so many people. And I find that just extraordinary.”

Given that Christie’s novels are some of the most widely read stories in the world (matched only by Shakespeare), it is a remarkable testament to Suchet’s craft that his embodiment of Poirot is now almost synonymous with Christie’s original. Despite such strong association, however, he has avoided being typecast, thanks in part to the seriousness with which he undertakes each role.

“I remember reading in the press a few years ago a reviewer say he was ‘looking forward to David lightening up a bit.’ I think what he was latching on to is that I do take my work and my responsibilities as a character actor very, very seriously. You see, I sat down one day and I sort of analysed myself. ‘What am I doing with myself?’ And I realised that there are basically – and this is rather simplified – two types of writer for the public. There are those who write novels to be read, and there are those who are playwrights writing to be performed. Sitting at my desk, I suddenly found a purpose. I would dedicate my life as an actor to serve my writers. When I started reading [Christie’s] books, I realised that [Poirot’s] voice had never been shown before. I didn’t have to work out how to play him; I just followed my raison d’etre for being an actor. I became the Poirot that hadn’t been seen, and all of a sudden the readership was saying, ‘I can see him! He’s suddenly real!’ That was fabulous for me. So yes, I take my work very seriously, because I found a very serious purpose for it.”

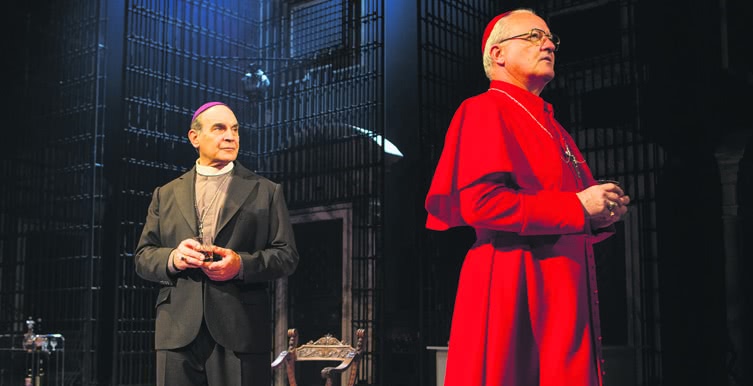

Suchet’s role as Giovanni Benelli once again finds him undertaking a remarkable character, albeit this time one who actually lived. Benelli was instrumental in the 1978 election of Pope John Paul I, who after only 33 days in office was found dead. Accusations of murder were instantaneous, and it is into this atmosphere of conspiracy and doubt that Suchet leads his audience.

“Not much is known about him. No literature was written about him; he was never described in what he would wear or what he sat down and had for breakfast. What we do know about him is extraordinary. Having lost his best friend, he goes through a great crisis of faith. Faith in God – how can you let a Pope die? – to faith in the Catholic Church itself. Was it murder? Who murdered him? What this play does extraordinarily well is to take away the fourth wall of the theatre and allow the audience into the Vatican. You don’t come into a religious organisation, even though all of us are walking around in cardinal robes. You enter parliament, you enter argument, you enter politics. You enter fighting and power play, a world that you didn’t know existed behind those walls.”

While news of the Pope’s death 36 years ago is a vivid memory for Suchet, for the majority of readers here it is likely to be little more than the impersonal stuff of history, something that occurred before many of us were born, and as such has the same distant veracity as other global events like the assassination of JFK or the Great Fire of London. But as the adage warns, history repeats itself, and Suchet is keenly aware of the scope these past events and personalities can hold on today.

“Well, for me it’s recent history. In a way it’s still happening now. There are cardinals in the Vatican now who are worried about the safety of Pope Francis, because that conservative guard is still around, who want no change, who don’t want priests to be non-celibate, who don’t want priests to marry, they don’t want contraception to be investigated. All of these things that are still going on. It’s quite famous knowledge that we don’t learn from history. It’s our great clichО as human beings. But if Pope Francis is successful, he will change the face of Roman Catholicism for the better.”

Suchet sips his coffee and glances out the window. Of course, there is no moustache or Belgian accent, but the curiosity and intelligence that hallmarked Poirot are clearly traits the two share. “There has to be reform for the right reasons,” he suggests. “Not simply to be popular, and that’s where the Church has to be careful. There are reformed churches now that are so charismatic, are so emotionally charged – are people going in there for themselves or are they going in there to worship God? I’m not here to criticise, I’m only saying, how far is reform within the Church a good thing, and how much of it is suspect? How much is any reform centred around popularity, and how much is it seriously examining a movement with the times, to be more open-minded because the times are open-minded?”

Before closing, I ask Suchet what his thoughts are on the various revivals of Sherlock Holmes that are now popping up around the world. He smiles, and as he answers, his mannerisms begin to change.

“Let me move it away from myself, and give it to you instead in the words of Hercule Poirot, when asked in one of his books about Holmes.” The way Suchet holds his shoulders and moves his hands suddenly shifts, and the pitch of his voice moves into a Belgian accent; suddenly, wonderfully, I am being addressed by Monsieur Hercule Poirot.

“Sherlock Holmes?” Poirot asks. “I do sometimes enjoy delving between the covers of his books. I do indeed enjoy him solving the crimes, which I of course solve before him. But one must remember, of course, that Sherlock Holmes … is only fiction.

The Last Confessionis playing atTheatre Royal fromWednesday September 24, tickets online.