Self-doubt has no expiry date.

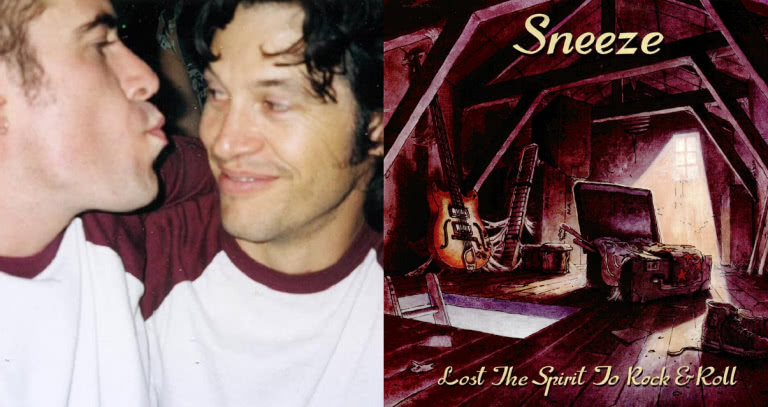

Even 15 years on from its release, Sneeze’s second albumLost The Spirit To Rock & Rollstill resonates, its undercurrent of pain and paralysis proving as biting as ever. It’s a significant record, one brought to life by two of the Sydney scene’s brightest talents working in collusion to create something both of its time and yet accessible to outsiders.

“[It’s] one of my all-time favourite records,” says Alison Galloway, drummer of Smudge and friend and colleague of Nic Dalton and Tom Morgan, Sneeze’s two halves. “It would probably have been ever better if they’d let me play on it, though.”

Smudge’s bass player, Adam Yee, agrees. “[Nic and Tom] are the Lennon and McCartney of Australia,” he says. “I’m just not sure which one is Linda and which is Julian.”

‘Favourite’ is a word that gets used a lot when people talk aboutLost The Spirit. It means something to people. It matters.

“Lost The Spiritis still one of my favorite albums,” says Chad Bennett, a Sneeze fan. “I remember when it first came out I would play it for people over here in the States who had no idea who Sneeze were or what to expect. I would slip it into the background while hanging out and it stuck with people.”

The album is a kind of roll-call of early 2000s Sydney talent, a record bursting with guest spots and deeply rooted in the language of the city’s Inner West. Songs like ‘I Believe In Marrickville (Parts 1 & 2)’ are grounded in a local vernacular, and there are none of the US-aping rock cliches so common amongst young Aussie bands. Dalton and Morgan sing in unaffected accents, rather than Yankee drawls.

But despite the Sydney-centric DNA it shared with a number of other bands on Half A Cow Records, the label that Dalton himself co-founded, the seeds forLost The Spiritwere sewn overseas. Though at the time Morgan was best known as the lead singer of seminal Australian rock outfit Smudge, he was also writing songs for American band The Lemonheads, a group for which Dalton played bass. It was while on tour with Evan Dando of that band that Sneeze was born.

“Evan had rented a shack on Martha’s Vineyard and Nic and I went to the States for a tour,” Morgan explains. “One night, as we were all driving back to the house, Nic just jumped out of the car and ran into the woods. He was gone all night. The following morning I was still awake and playing the chords to [Smudge song] ‘Yah We Are Cruel But We Have Our Agenda’ backwards as Nic appeared from the wilderness. He sat down and asked, ‘What’s that? It sounds good.’ So we started writing.”

It’s a memory that stands out for Dalton as well. “I [slept] wrapped up in a stranger’s boat’s sail,” he says. “Scrambl[ed] my way through the bushes at six o’clock in the morning and there’s Tom sitting outside the shack with a guitar. We wrote all of [album opener] ‘Wu-Li’ then and there.”

–

Lost The Spiritis an unashamedly sad record – a tragedy-laced document of a difficult time in both Morgan and Dalton’s lives. “My girlfriend had recently left me, and from memory Nic’s relationship had just gone bust as well,” says Morgan now. “We felt old, alone and washed up. Both probably drinking too much. And I had come to the realisation that almost all of the money I had earned through songwriting I had spent on drugs … It’s crazy now to think that at 28, I imagined my life was over. But I did.”

For Dalton, the record was an opportunity to demonstrate the band’s collective talents. “We started recording in 1998 and finished in 2001,” he says. “Tom and I spent all our own money – over $25,000 in fact – until we were completely happy with the finished record. We felt like we had to prove – to ourselves, to our friends, to other bands and the music scene – that we could make a top-shelf album that wasn’t a fuzzy pop throwaway.”

Unlike Morgan’s work with Smudge or Dalton’s with The Lemonheads and his own band, Godstar, Sneeze took a great deal of inspiration from soul songs from the ’60s. It was this mash-up of styles – the suave and the sinister, the exuberant and the exhausted – that madeLost The Spirit what it is. “I made a compilation tape called Two Lonely Pillows that was full of late ’60s and early ’70s soul songs,” Dalton says, explaining the album’s sonic starting point. “Songs by Laura Lee, Don Covay, Honey Cone, Candi Staton. That was pretty much the original inspiration. Songs where the guy sings about making love to some woman whilst he’s out on the road and meanwhile his old ol’ lady’s back at home making love to someone else. These songs with the most beautiful cruisy music with hilarious lyrics sung with such seriousness and conviction.”

“We didn’t want to simply copy [’60s soul] tunes but we thought it would be cool to put our ‘little white lives’ in them by singing about what we knew,” Morgan says. “Like a marriage of what we were and what we weren’t … It seemed cool to write about the places we were living, and things we had observed in a style that was foreign to what we would normally do.”

The track that best showcases this divide between highbrow stylings and lowbrow subject matter might be ‘Tittie Bar’, a typically Morgan-esque sorta sad, sorta funny exploration of a night inside the titular club. “Nic and I decided to go to Crazy Girls, the famous tittie bar in Hollywood. It was something we had never done,” Morgan explains. “A few weeks later, on the way back to Australia … Nic went to dinner with a friend and I went to another strip club. Going to one of these places by yourself on a Sunday night is a totally different experience. There’s no party atmosphere. Just a small group of lonely men sitting quietly. And I was one of them.”

‘Casual Cashew Daddy’ is another of the album’s signature tracks, a tender love song peppered with Dalton’s endearingly odd character asides. “When we break up I gets to keep the makeup / And the licorice jar”goes the chorus.“I wrote that song sitting on the steps of a hotel in Melbourne waiting to play a show,” says Dalton. “It was about me and Lara, who was sitting on the steps with me while I wrote it. She was the Sneeze drummer at the time. She would come around to my home in Annandale and eat all my cashews, use the phone and have a shower. Bless.”

The pair worked collobaratively, trading and vocal duties constantly. “We jumbled it up a bit. I actually didn’t want to sing any of the songs,” Dalton says. “There’s songs that Tom sings that I wrote the lyrics to and I think I only sing two or three songs solely by myself. We had a lot of other singers too.”

Despite a host of guest performers (including, but not limited to Lara Meyerratken, Jess Ciampa, Dan Estabrook and Nicole Forsyth),Lost The Spiritis audibly Morgan and Dalton’s baby. Their loneliness is all over the record, disguised under a thin layer of excess and soul swagger. Though ‘Doctor Of Love’ might be the album’s most optimistic track, even a cursory look beyond the surface reveals a seam of irony and distance. Dalton and Morgan make music in the style of the men they would like to be, rather than the men they supsect that they are.

The album quickly resonated with fans upon its release. The group launched the record “at the Annandale in 2001 … with a huge nine-piece band” says Dalton, and later appeared on television to promote it. The sight of the group in the TV studio – Morgan tall and hypnotically still, Dalton kneckerchief-ed and tinkering on an electronic keyboard – provides a good visual expression ofLost The Spirit‘s themes. The band appeared energetic yet considered. Sincere yet knowing. Removed and yet deeply connected.

–

Lost The Spiritmight not have ever been the massive success that so many people wanted it to be. But such a detail is ultimately inconsequential. What matters is how it changed the people who heard it. Even now, people talk about the record with the kind of fervor reserved for the things that have genuinely moved them. For Andrew Calvert, lead singer of Wifey and occasional player in Sneeze, the song that means the most is ‘Wu-Li’, a track on which then “thirty friggin’ three“-year-old Nic Dalton worries about being over the hill. “I’m 38 now, boring job but still no wife and kids, and every time I hear ‘Wu-Li’ think of how I’ve lived a whole other lifetime in music in Sydney since being told we were too old,” says Calvert. “It’s crazy how laden with meaning a song can get because the writers reference age and aging.”

Dalton himself remains significantly proud of the record. “If I wanted to impress someone I would play them ‘Too Much Man To Be My Woman’,” he says. “I still think [Lost The Spirit] isthe best thing Tom and I have ever done.”

More than anything, Lost The Spirit still works because it’s true. Its deliberate layers of artifice reveal something natural, something raw. “That’s how we stopped it from becoming parody, I think,” Morgan says. “We had empathy for the protagonists because they were us. Honesty and truth aren’t the same thing. So we wrote the truth.”