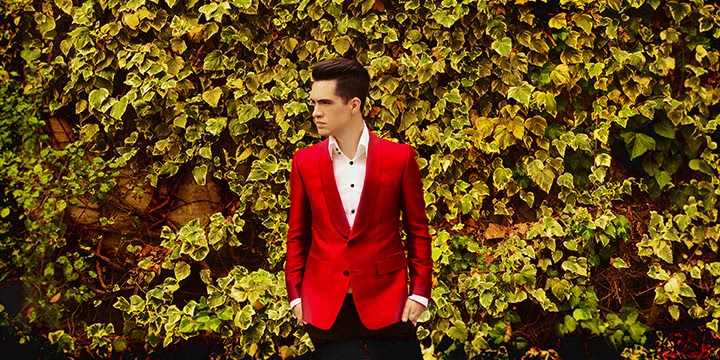

“I’m just such a selfish bastard,” laughs Brendon Urie, the sole remaining original member of Las Vegas’ theatrical rockers Panic! At The Disco.

Bursting onto the scene in 2005 with their breakthrough album, A Fever You Can’t Sweat Out, Urie and his then-bandmates Ryan Ross, Spencer Smith and Brent Wilson washed over the world of pop-punk and alternative rock with a concoction of their own, influenced by burlesque, classic literature and straight up pop-rock licks.

After winning over the masses with their zany lyrical wit and grand instrumentation, the subsequent departures of bassist Wilson, songwriter Ross and Wilson’s replacement Jon Walker signalled the end of Panic! as we knew them. But for the ever-energetic frontman Urie, his persistence in flying the Panic! flag, exclamation point in tow, has been all about evolution.

“A lot of artists fall into that gap of, ‘OK, I want to do something different,’ but they just write something faster using the same instrumentation, writing style and structure,” he says. “I don’t like to do that, because I get very frustrated. I’m so mindful of that, that I like to compare songs all of the time, so it gives me a sense of what I should do and what I shouldn’t do.”

The strategy is working. Look back at each Panic! album since their debut and its follow-up, 2008’s Pretty. Odd., and the transformation is unmistakable. 2011’s Vices & Virtues still carried some of that theatrical magic but with shorter syntax and more rock-fuelled tones, while Too Weird To Live, Too Rare To Die! arrived two years later with an increased electropop presence and more of a hip hop flavour than before.

Now it appears yet another incarnation of Panic! At The Disco has begun. But with the impending release of their new album Death Of A Bachelor, it emerges that Urie has maintained one particularly unexpected influence since the beginning.

“I’m huge [Frank] Sinatra admirer,” he gushes. “Some of my earliest memories are as a child at Christmas, opening my presents and hearing Frank sing ‘Jingle Bells’ and ‘White Christmas’. He’s been a huge part of my life.

“I actually wanted to do a Sinatra album, and so the first song I wrote in that style was the title track. I wrote it just purely with piano and vocal, but I had the string arrangements in my head, so I was like, ‘Cool, I know how to do this.’ But as I sat down to write these arrangements I realised, ‘I don’t know how the fuck to do string arrangements!’”

It was this hurdle that forced Urie to take the classic Ol’ Blue Eyes vibes and apply them to a completely new musical context. “The thing I do know how to do is produce tracks,” he says. “So I took a track that I had been working on months ago and mashed the two together. I don’t know how putting this beat behind a Sinatra style worked, but it sounded so cool! It gave me such a happy feeling that then took the whole album in that direction.”

Throughout the record, the many tones that make up Urie’s distinctive vocals soar over driving guitars and the glitches and bops of electronics. The exception is the closing ‘Impossible Year’, which Urie describes as his finished interpretation of a traditional Sinatra ballad. “Just [my] voice. No double, no Auto-Tune, just baring it all and putting it all out there.”

But when asked what would happen if, hypothetically, Sinatra were to provide any feedback on his homage, Urie laughs. “I would hope that he would critique my vocals and tell me, ‘It’s not good enough, they’re sloppy.’ That’s what I would hope he would say, because he is phenomenal and flawless. He is ‘one-take Sinatra’.”

Alongside ‘Impossible Year’, Urie looks back with fondness on the creative process he undertook for the album as a whole.

“It kind of took me back to my roots. If I got bored of one instrument, I’d just move onto another. I have a studio [at my house], so I just ended up knowing exactly what I wanted to do when we went in to record properly. It just became easier to get my point across and more fun to see how far I could take my original ideas.”

The experimentation with different sounds was, as Urie says, his “saving grace”. Yet the Panic! At The Disco touring band, consisting of Dallon Weekes, Kenneth Harris and Dan Pawlovich, were often left scratching their heads when Urie brought his creations to the rehearsal room.

“We actually just rehearsed a couple of days ago with these new songs,” he says. “There’s a song on the album called ‘Don’t Threaten Me With A Good Time’. I sat down with the drummer Dan, who is a phenomenal and talented drummer, but he just couldn’t figure it out. After a while he was like, ‘OK, I’ll get it,’ and he did after one try. If you push other people to do their greatest, they’ll come out on top.”

Despite how jovial and jittery Urie is in anticipation for his new release, he is mindful of the fact his newfound creative freedom came at a cost. It was around two years ago that founding drummer Smith wrote an open letter detailing his battles with addiction. He officially left Panic! last April, and though Urie mentions no plans for Smith to make a return to the band, the pair’s relationship remains strong. “Spence and I are still the closest of friends,” Urie says. “It’s awesome”.

Looking back on what has already been a long musical career, it seems Urie has always been destined to be the sole orchestrator of his creative world. Out of all the bands he has played in from his school days until now, he draws one clear conclusion.

“I just got bored with people,” he says bluntly. “I started making demos on my own. I played guitar, drums, I did vocals and everything else. Because – and it sounds really shitty to say out loud – but I couldn’t stand being with people. It sounds kind of cocky, but they weren’t up to my calibre.” He laughs, “They weren’t grade A.”

“It took me a while to realise if you want something done then you should do it yourself. That’s how Death Of A Bachelor came about.”

[Panic! At The Disco photo by Shervin Lainez]

Panic! At The Disco’sDeath Of A Bachelor isout Friday January 15 through Fueled By Ramen/Warner.