Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s dream was to win the Oscar for best director, and be ugly on the front cover of Time magazine. He achieved neither. Instead, from 1969 to his death from a cocaine and barbiturate overdose in 1985, he made some 40 ground-breaking films, acid-laced melodramas that were about love, and trauma, and politics, and cruelty. With his films, he once explained, he was trying to build a house. Some films were walls. Others made up the floor. Others still were the windows, big and clean enough to let the light in.

What all his films share is the same complex, cock-eyed view of love. Growing up around parents who could barely tolerate one another in a Germany ravaged by the Second World War, Fassbinder spent his adulthood telling interviewers that marriage should be abolished and feverishly writing and directing films about lovers who inflict great pains upon each other. “I was lucky, growing up in a family where close relationships didn’t exist,” he once told the New York Times. “Today I’m kind of happy about it. It makes me freer than people in general.”

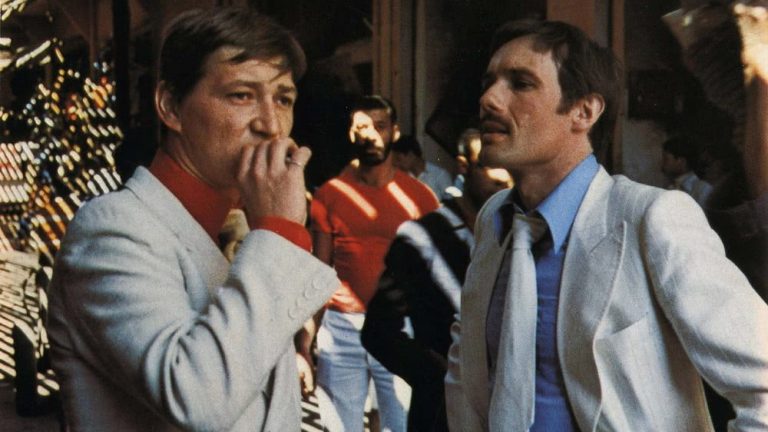

Watch an interview with Fassbinder here:

Certainly it’s true that relationships in Fassbinder’s films often fall apart due to the absence of cruelty, not the introduction of it. In Ali: Fear Eats The Soul, a 60-year-old window cleaner named Emmi falls for the titular Ali, a young Moroccan man, and is forced to overcome the discrimination and racism of her close-minded neighbours. She does, rather nimbly. It’s only when the world around her accepts the relationship that things sour. When her neighbours move on from their prejudices, Emmi takes on the mantle of tormentor herself, bullying and needling her young lover. She parades him about like a show pony, inviting her friends to feel his muscles; to stroke his skin. When he shirks away, she dismisses him. “He has his moods,” she sighs. “It’s his foreign mentality.”

“[Fassbinder] felt that relationships unavoidably have a power struggle at the core of them as two people establish their dynamic; and that the fear of losing love once you have it is tied to the fear of life’s other inevitable conclusion, death,” explains Eric Allen Hatch, a film critic, one-time director of programming for Maryland Film Festival, and one of the brains behind Baltimore’s soon to be launched non-profit video store, Beyond Video. “In that sense, coming to terms with mortality would make someone more capable of real love, because they wouldn’t then damage and pervert love in their fearing the loss of it.”

That melancholia was not artifice, either: Fassbinder lived his life with the same bleary-eyed intensity and destructiveness with which he made his films. “We could almost reconstruct him from the DNA embedded in his films,” Hatch says. “He lived his life hellbent on converting his every thought and feeling into vital cinema.”

Many have called Fassbinder cruel.

The budget for Fassbinder’s post-war melodrama The Marriage Of Maria Braun was blown out by the cash he demanded from his longsuffering producer, Michael Fengler, so as to support his taxing cocaine habit. He drank and smoked to excess; years later his muse, Hanna Schygulla, told The Guardian he smelled and looked like “a rebel filled with angst”. He’d often start his day on set asking for ten Cuba Libres, nine of which he’d slurp down, and one he’d save for throwing at his crew. And his lovers, both men and women, were often as passionate and prone to occasional bouts of violence as he was.

“Whenever two people meet and form a relationship, it’s a question of who dominates whom,” Fassbinder once told Cineaste magazine. One of his lovers, El Hedi ben Salem, attacked three people with a knife, ended up in police custody in France, and committed suicide in his prison cell. Another, Armin Meier, took his life a little under a month after he and Fassbinder broke up.

“You get the sense from his work that this is a person that’s both experienced and (especially, it seems) caused great pain in relationships,” Hatch says. “There’s something cathartic about seeing extreme feelings expressed and explored honestly, knowing someone else has been to these very dark places. But he doesn’t just show them to us… Behind our tears or dropped jaws or dark laughter, we might learn something about ourselves and how to treat other people better.”

—

Many have called Fassbinder cruel. The critic Kent Jones described his films as “blunt instruments”, and it’s true they often have a kind of elegant sadism to them. The Bitter Tears Of Petra Von Kant, which Andrew Sarris somewhat reductively described as being about the “problems of lesbians”, is a tangle of unpleasantries; in a baroque, decadent bedroom, the young Karin spurns fashion designer Petra von Kant, who in turn spurns her put-upon assistant Marlene, a white-faced punching bag who has been so bullied and belittled as to be rendered mute.

And in Fox And His Friends, the deeply naïve titular hero, played by Fassbinder himself, isn’t safe from disrespect even in death. “One gets the sense that [Fassbinder] wanted a revolution to bring about a better world,” Hatch says. “But sadly, he simultaneously seemed to believe people are too deeply flawed to build that better society.”

Watch the trailer for Fassbinder’s The Marriage Of Maria Braun here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZV4IXLz5YMM

Fassbinder’s endings are often abrupt. Characters explode; sometimes literally. They pivot on their heels and act in new, surprising ways: Petra promises Marlene she will change – that she will be kinder, better – only for Marlene to pack a suitcase and leave. His lovers hurt each other in ways so new and unusual as to resemble genuine breakthroughs.

His endings are rarely happy. But despite their morbidity, and despite the claims of cruelty that have dogged his legacy ever since his death, underneath it all, Fassbinder always leaves room for some lopsided, emaciated form of hope. He was an optimist, albeit of the most bitter, resentful sort. Love, for Fassbinder, is cruelty. Love is a kind of death. Love is violence, and trauma, and pain. But sometimes, love is a reprieve.

Ali: Fear Eats The Soul ends with Ali in hospital, suffering from a burst ulcer. The doctor, his face blank, speaking in the clipped, affected tone common to so many of Fassbinder’s characters, warns Emmi that even if Ali fully heals, he’ll be back in hospital again soon. Ulcers are common to foreign workers, he says. He’s probably right. But Emmi doesn’t listen. She goes over. Holds Ali’s hand. And she stays there, looking down at him, till the screen fades to black.

The Marriage Of Maria Braun is playing at Sydney Film Festival on Saturday June 16; for more, head here. Fassbinder’s celebrated series, World On A Wire, is available to stream on Stan here.

For more film content, head over to our review of Upgrade, here.