In 1972, an angry film student in upstate New York spent US$2200 on methamphetamines. Not the smartest idea, given he only had $800 left in his budget to make his film. That film, shot without synced sound, mostly in a warehouse, is about an ex-con who decides to make snuff films to get revenge on the world that spurned him. The original cut of this grimy picture ran three hours long and was called The Cuckoo Clocks Of Hell, in reference to Kurt Vonnegut’s book Mother Night. Rumours still swirl that the original theatre at which the cut was shown burned down in an ensuing riot, so maddening was the movie.

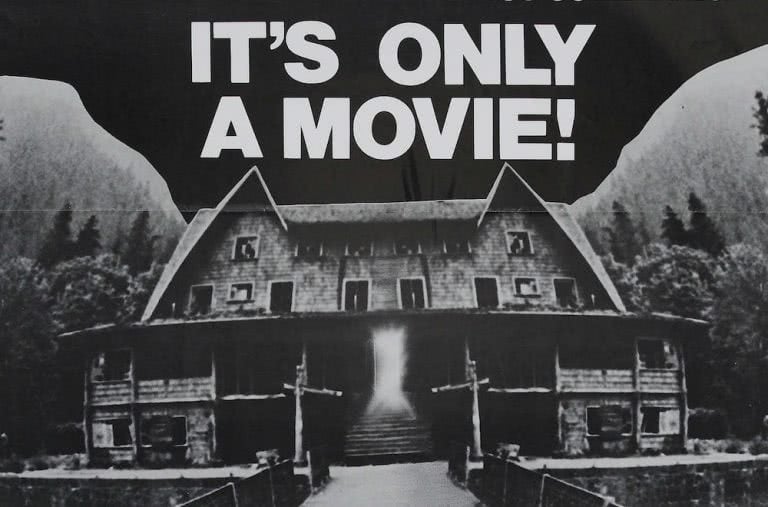

What is known is that when the distributors saw the film – messy and indulgent, as disturbing as it is cheap – they freaked out. They cut the film down to less than 80 minutes, and in 1977, they quietly released it under the name The Last House On Dead End Street to capitalise on Wes Craven’s 1972 film The Last House on the Left.

For decades after its release, no one knew who made The Last House On Dead End Street, because everyone involved in its production used pseudonyms. Partly due to those pseudonyms, partly due to its scarcity (it was available for years on a South American VHS copy known as “The Venezuelan Rip”), partly because it’s fun to believe in ghost stories, rumour spread that Dead End Street is a real snuff film.

It took until 2000 for all the mysteries to be dispelled. On an online message board, a man named Roger Watkins came forward as the writer, director, editor, and star of Dead End Street. Not only that, but he revealed he had also made a number of adult films under another pseudonym.

For decades after its release, no one knew who made The Last House On Dead End Street, because everyone involved in its production used pseudonyms.

In niche circles, Roger Watkins became a star, sought out by underground zines like Ultra Violent for interviews, welcomed to horror festivals, fans finally able to heap praise upon a barely-known horror maverick – the kind of filmmaker whose sub-basement obscurity only intensified the obsession of his fans. Watkins didn’t quite understand the praise, though: in interviews, Watkins showed a mild disdain for his chopped up debut, calling it “incompetent.”

Which is not an unfair descriptor. The Last House On Dead End Street is often just that. It’s also repulsive and cruel, pretentious and offensive. It’s a movie where a woman dresses up in black-face at a party and is whipped, while her pornographer husband talks about how no one is satisfied by normal stag pictures these days; how they’re always looking for harder stuff. It’s a movie where the main character cackles as he and his entourage film the murder of a blind homeless man. It’s a truly reprehensible film.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

Watch the trailer for The Last House On Dead End Street below

But it’s also one of a strange power, of pure vile horror that gets deep into the brain and leaves one’s nightmare’s sticky for weeks. Beyond all the mess, there’s true talent at work, real intelligence behind the camera. Watkins’ compositions are purposefully discomfiting and even mythic in their broad strokes of colour and blinding lights. Negative space fills the frame, making every moment feel empty, like it’s happening at the heart of a black hole.

Even the dubbing, so poor that it’s often tough to tell exactly who is speaking, adds to the sense of disconnect, leaving the viewer floating without anchor; the only audio constant being the in-your-face sound mixing, all old organ music and heartbeats blasting over barely audible, murderous whisperings.

There’s an anger beneath all the horror, the scream of a disillusioned young man trying to comprehend the corruption of a Post-Watergate, Post-Manson America. Here’s a creator asking, “What could be worse than what we see on the news every day?” and then trying to answer that question; trying to control the result. In a memorable scene our ‘hero’, the director, screams at a meddling producer to “Stay behind the screen!” but it’s no use; everything’s already lost.

Watching Dead End Street, it’s easy to imagine Watkins going on to have a distinctive career as a horror filmmaker. Alas, the bungled release of his debut left him in the lurch. Needing to support his family, Watkins turned to the hardcore pornography scene to pay the bills. Over the next decade, Watkins made a series of bleak, deeply un-erotic porn films, and, despite his vocal distaste for the genre, showed a clear artistic ambition that often overcame the disreputable mode of filmmaking.

His porn career began in 1980, with Her Name is Lisa, the slow, doomed journey of a young woman (Samantha Fox) being exploited by a ladder of those she grows to trust and then hate, including a proto-Terry Richardson type. Even if the ultimate product is more a fascinating contradiction than successful film, Watkins manages some surprisingly poetic sequences in between the anatomical sex scenes.

Watch an interview with Roger Watkins from 1975 below

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAdAipnKyl8

Though he made a couple of lighter flicks after Lisa, it wasn’t until 1983 that Watkins hit his stride. That’s when he released Corruption, a seedy, metaphysical critique of ’80s excess and pornography itself. Business deals in a brothel where men “renounce love”, a peep show that transports the viewer into their debased fantasies, a mime laying with a corpse on an altar; all these strange, scary, sometimes goofy images, presented with consideration of aesthetic and theme that reflects Watkins’ debut, trying and failing to reconcile oneself with the exploitation they seek out on their theatre screens.

In 1985, Watkins made his last celluloid feature: American Babylon, a more honest version of American Beauty, where middle-aged suburban men fight their growing sense of impotence by watching industrial stag films together and having miserable affairs, eventually making their own, supposedly “honest” porno that will reflect their virility. Of course, it only highlights their irrelevance. Even as a comedy, American Babylon is as bleak as Watkins’ horror pictures, and it again showcases the scathing self-critique of a director who felt forced out of his dream profession into the back alleys of Hollywood.

Roger Watkins slipped through the cracks, but he managed to make a bunch of movies in that dark hole, toiling unknown for decades.

The story of Roger Watkins feels oddly poignant in the age of Peak Content, when a million movies are released and immediately left to rot in the bowels of Netflix and Stan and VOD, with no marketing to speak of; it’s so easy for creators to slip through the cracks, to never get the recognition they deserve.

Roger Watkins slipped through the cracks, but he managed to make a bunch of movies in that dark hole, toiling unknown for decades. It’s lucky that some light was able to penetrate his grimy, beautiful abyss before his death in 2007; for a brief moment, he was finally able to get out from behind the screen.