The sputtering elegance of long-distance phone connections threatens to turn this interview into a farce before our conversation has even found its feet.

This would not be entirely inappropriate, given James Thierrée’s unique family lineage; with circus performers for parents, one of the greatest playwrights of the 20th century, Eugene O’Neill, his great-grandfather and – were that not enough – one of the most celebrated performers of all time, Charlie Chaplin, his grandfather, you can’t help but anticipate chatting with Thierrée will be an animated experience.

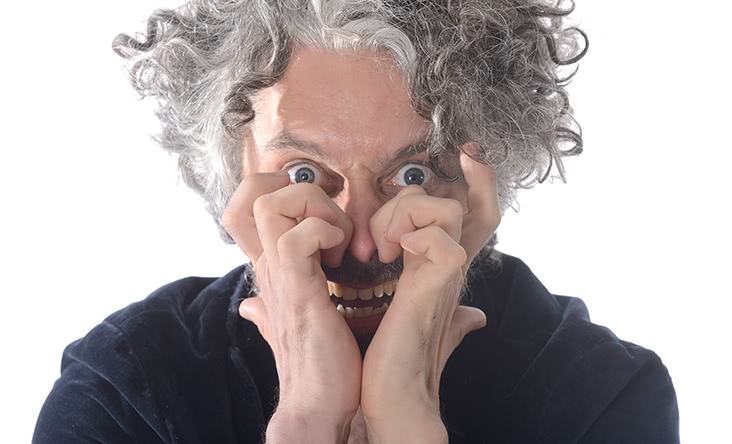

He doesn’t disappoint, and the lyricism of Thierrée’s responses is entirely in line with the remarkable imagery and invention of his stage career. Men becoming beasts, sets and props gaining human characteristics, dance, acrobatics and slapstick – anticipating what to find in one of his shows is a task not even Thierrée himself can contemplate.

“The good thing with my work,” Thierrée chuckles, “is that the subject of the show is always cryptic. This is absolutely obligatory in what I do. I always need to further the work, to refine the language, to understand what it is all about. I start a show without knowing exactly what the whole thing is, and the logic comes out as we work, as the artists and I interpret it onstage. This show was interesting since when we started touring it I wasn’t onstage, which was a first for me. It was harder for me to be on the outside looking in than to be onstage and understand what was being drawn out. But the work is always continuing, and becomes more and more interesting. It started as a very dark and choreographic show, with this palette of extremely toxic atmospheres about power and tyranny, a kind of almost fascistic society that leads to some sort of revolution. But as we toured the show, the humour began to turn up, other subjects emerged. The search for beauty, the capacity to realise transformation. It’s an interesting subject. I like simple themes that can deepen, that can expand.”

Thierrée’s latest creation, Tabac Rouge, draws on a history of circus and theatre that he has been almost divinely placed to absorb. His earliest memory is of watching from the wings as his parents took to the spotlight, performing in the kind of sprawling, chaotic circus that has faded today.

“My first memories are literally being onstage, waiting for my mother and father. That was more of a circus, but when theatre came it had a very big impact on me. The sounds, the use of light and body together. I was very young, and we were always on tour, making friends with these huge circuses that don’t exist anymore. Proper three-ring circuses. Just huge enterprises of entertainment and logistics, absolutely mad scenes of trucks putting up the tent, the beasts, the smells, the sounds of metal as the seatings were assembled. My first impressions are almost more about the buildings, the house – the tent or the theatre – as a physical, pulsing place. The beauty of that simple building, with its simple rules: people sit on one side, and on the other is this space where you are constantly reinventing. That was my first theatre experience.”

Watching footage of Thierrée’s past performances is an exercise in astonishment (and if you don’t believe me, be sure to check online for his performance with Symphonie du Hanneton). The strange physicality of his movements and the otherworldly sets combine to create a surreal landscape laden with meaning and potential.

Many touring troupes today utilise elaborate sets to dazzle audiences (occasionally at the distracting expense of the performer’s actual talents), but to Thierrée, the presence of props and the development of the set is as fundamental to the show as having an audience to actually witness the story unfold.

“I enjoy sets that are interactive. The set is the first thing I will think about, before I even know what will happen in it and what the show will be about. There is so much meaningfulness in the set, in the fabrics, in the construction. I’m very affectionate with props and sets. I feel like the attention and the time you have given to that will come out to the audience, and that’s where we are different from cinema. Cinema, they construct and they destroy, it is for one purpose only and then it is gone. In theatre you live with that set, and the strength of it is only going to grow as you feed it with more performances. When we put the props back in the warehouse in Burgundy, I look at all these costumes and cases, all of these pieces of metal – it’s like they’re part of the family. You still don’t know what to do with them. After the show, there’s no grave for sets. Where do they go, what do we do with them? Like elephants, they must go off and die in some secret place,” he laughs.

It is a wonderful notion, and leads you to hope that somewhere out there is some quiet cardboard forest in a disused theatre where restless sets heave and transform, every seat occupied by empty costumes of empresses and pharaohs, spear-carriers and shepherds.

“I think it’s all about movement,” Thierrée continues. “You need to create movement in the audience. I’m talking about internal movement, emotional movement or even cerebral movement. It’s like missing part of the puzzle. If things are not clear in the beginning and you must take the audience on a journey, you might not want them to be completely reassured. I’m not talking about trying to make them feel uneasy, but just to let them have a part in the interpretation of what they see. I think that’s very interesting. I think that’s why I never indulge in over-explaining the meaning of what I do. It’s theatre about theatre, about the power of the imagination; the power of moving your perceptions, your instinct and impressions. It’s a way of creating movement in thoughts, to look twice and think differently. It’s interesting, but I wouldn’t try to pinpoint what they must understand, or what they must do to be part of our show. It’s a mystery, and you should never know exactly what part everyone is going to play.”

Following his Sydney Festival appearance, Thierrée is already looking ahead to his next projects, of which one is an opera about Orpheus and Eurydice. Such a classic myth falling under his direction is an intriguing notion, although his ambition may soon branch out away from the stage.

“Well, it’s something that is often very dangerous, but I feel I could try and make a movie. Writing and directing. That’s a slow process, so we will see where it goes. Trying to see what I can take from my theatre experience and take it to the screen. There are not that many things, except the energy and the will to accomplish an idea. Maybe I can take this. People don’t dream the same way in front of a screen as they do in front of a stage. But then, anything that is a bit dangerous, I will probably be coming along.”

Tabac Rouge will be playing at the Sydney Theatre during Sydney Festival on Thursday January 8 – Friday January 23. Tickets are available through the Sydney Festival website.