12 months on from Prince’s death, in a year of profound sadness for the music industry, JOSEPH EARP explores the culture of super fandom and how we respond when our heroes depart this world.

They all remember where they were when they heard the news. For the Australians, the stories go pretty much the same way: they woke up, groggily scrolled through their Facebook feeds, and found themselves met by a thousand versions of the same story. He had died overnight Australian time, so it was different from when David Bowie passed away in the afternoon. That story was a rumour before it was fact – a digital whisper, easily dismissed as gossip by the optimistic. But this was different. The sources had already been confirmed. Prince was dead.

“I felt almost a little bit silly to be so sad about it,” says a long-time Prince fan named Martin. “You don’t expect to be cut up when the musicians that you love die – or it kinda feels weird when you do. Why should it even matter, really? You’ve never met them and never spoken to them or anything. There’s no reason at all to be sad really, when you think about it. You don’t know these people. But also, you kinda do.”

It’s a sentiment many Prince fans share. For them, he was no stranger. Some had seen him in the flesh only a few months earlier on his Piano And A Microphone tour of Australia, a sold-out string of surprise shows that saw him croon his way through his back catalogue. How could it be that he was there, onstage, and then six weeks later, gone forever? How can someone be so vibrant, and colourful, and alive – and then suddenly not?

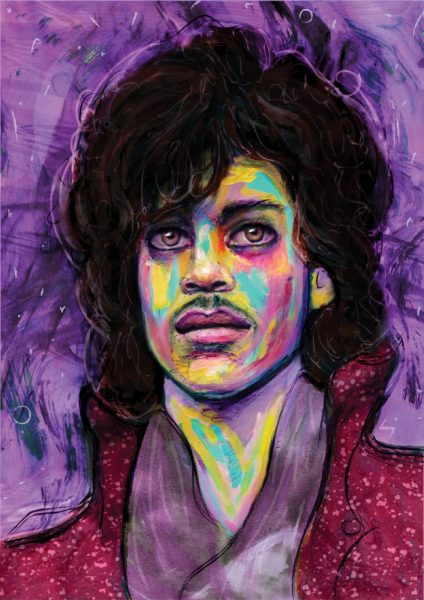

Prince by Amy Summer

“I know there are many people who don’t quite understand how it is possible to grieve for someone so deeply when you didn’t actually know them personally,” says Juliet Letteri, a Sydney musician and DJ who performs under the name Black Cashmere. “But I can’t control this connection.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

Letteri considers herself lucky: she didn’t have to find out about the death via Facebook. “I woke up on that Friday morning and noticed my phone wasn’t where I left it beside me,” she says. “My mum came in the room with my phone in her hand, sat on the end of the bed and told me that she had bad news. She took my phone while I was sleeping as it kept flashing from all the calls and messages. She wanted to be the one to tell me that Prince passed away.”

Parents played a vital supporting role for a number of other fans too. Richard Lewis, an American with an enviable collection of Prince memorabilia he has been amassing since the age of 11, called his mother’s voicemail when he heard the news. “She has been dead for a year,” he says. “But I really just felt like I had to hear her voice. I felt silly, but I did it anyway … When I was a little boy, she used to dance with me around the living room to ‘Purple Rain’. That’s the first thing I thought of.”

Ruby, a young musician from Spain, read the news on Twitter, threw her phone across the room, ran to her father, lay in his lap and sobbed. “He thought something really terrible had happened,” she says. “He was going, ‘Who hurt you? Who hurt you?’ with his voice all scared. I couldn’t even say anything to him. I was crying too much.”

Some fans had to call in sick from work. Lloyd, the admin of a low-level Prince fanpage on Facebook, told his boss he had pneumonia, lay in bed, and polished off an “entire tub of cookies and cream ice cream”. LaRon DeRousselle, a Prince impersonator, spent the day at home, “watching reactions and celebrity commentaries” on the television.

Less lucky was Stephanie Prade, an American Prince fan and self-confessed introvert who was already sitting at her desk when she heard emergency personnel had been spotted outside Paisley Park, Prince’s Minnesota headquarters. She told her boss she needed to leave. “In my heart, I knew it was Prince’s time,” she says.

She drove back home, let herself in and sat by the telephone. She prayed a little too. One can imagine Prince would have appreciated the gesture – he was devoutly religious, so full of faith that he had once requested one of his concert films open with the words “JESUS CHRIST IS THE SON OF GOD” emblazoned in big white letters across the screen.

But although she prayed, Prade knew what was coming. And eventually, it did. “I remember my mum called me, asking me to stay wherever I was so she could pick me up. I told her I was OK, but just needed time to be alone.”

Prade spent the rest of the day crying. She couldn’t calm herself down, no matter how hard she tried – not even when she limped back to work, not even as her colleagues tried desperately to console her. Eventually, it got so bad that she had to drag herself over to the hospital to get some shots to placate herself. Getting there was a trial – she had been crying so much her eyes were swollen shut.

Yet despite how hurt all these fans felt – despite how deep the pain went – Prince was not exactly an easy man to mourn. He was fiercely protective of his privacy; mistrusting of the internet; and, it must be said, more than a little unusual. He wasn’t some static object to be eulogised and wept over. He was a complex series of contradictory parts, a sexed-up Republican convinced the world was being secretly controlled via chemtrails who nonetheless composed some of the most touching and sensual music of the last 100 years.

People who loved and missed him couldn’t even share their favourite songs on Facebook: diligent about copyright violation, he had long worked to scrub YouTube of almost all his material. Those who wanted to honour him on their timeline only had a handful of live appearances to choose from – either a fiery performance of ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, a tragically truncated rendition of ‘Purple Rain’, or a cover of Radiohead’s ‘Creep’ that Prince had tried to suppress for years.

After his death, friends and colleagues didn’t say, ‘Hey, this is who Prince was,’ they said, ‘Look, we knew Prince personally and we still couldn’t tell you who he was.’

There was no way to stream his music online either. He resented such platforms, considering them just another way for music execs to take more than what they were owed. As a result, fans were forced out to record stores – only to find that most shops had already sold out of his entire back catalogue. “It was really weird,” says one shop owner. “There was just this very specific rush – everyone was looking for Prince albums and nothing else. People couldn’t hear [the songs] any other way.”

Then there were the anecdotes. We have come to expect them now: those stories cooed to us by late-night TV show hosts, carefully designed to help us grieve someone we never really got to know. And although Prince was honoured with his fair share of these posthumous narratives, they were different. They weren’t like the tales of striking generosity that came to light after the death of George Michael, for example, or the toe-curling sagas of chemical extremity that Lemmy’s passing prompted from those who knew him.

The stories about Prince weren’t as much uplifting as they were deeply, strikingly odd. These were tales concerning impromptu, highly competitive ping pong games, asides about snarky put-downs at high-profile events, and gossiped glimpses of The Purple One’s mythic capacity for shade. Even when they were funny and impressive – even when they made us feel a little better – these weren’t Spielbergian tales kissed closed with happy endings. These odes were downright Lynchian; bizarre shaggy dog stories that sounded too surreal to be true.

After his death, friends and colleagues didn’t say, “Hey, this is who Prince was,” they said, “Look, we knew Prince personally and we still couldn’t tell you who he was.” Prince didn’t make any more sense to us after he died. After all, who is going to be so stupid as to say Prince was nothing more than the 57-year-old man who passed away alone at home after a fentanyl overdose on Thursday April 21, 2016? No, death didn’t shatter Prince’s myth – it forced it to expand.

“Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called ‘life’” – Prince, ‘Let’s Go Crazy’

The music is so loud it drifts out onto the street, where two men in their mid-30s stand drunkenly discussing it.

“Even these songs, even songs that nobody knows, they are still good,” says the taller of the pair, a cigarette dangling between his lips. He begins jabbing at the slightly faded, stretched Prince T-shirt he is wearing; prodding away at the enigmatic smile slapped across the centre of the artist’s face.

“This man was absolutely, absolutely a fucking genius.”

“Right,” says his friend, who wears a crumpled suit and stares down at his feet as he speaks. Even when no one is addressing him, he nods randomly and tipsily at nothing in particular.

“I don’t even know this song, never heard this song before, but look – I’m dancing,” says the Prince T-shirt man, jiggling aimlessly.

“It’s ‘Shockadelica’,” a woman standing nearby says awkwardly, perhaps embarrassed to be butting in. Later, she tells me that her name is Julie. She says she doesn’t drink – that she would usually do anything to avoid going out to bars like this by herself. But she felt compelled to come down to Cafe Lounge in Surry Hills tonight, even though it took considerable effort to swallow down her anxiety and just loiter here out the front. She had to, because she had to come and listen to Prince’s music on the one-year anniversary of his death. She had to be near people dancing to his songs, even though she did not feel like she could join in. She just wanted to watch. She just wanted to feel it.

“Oh, she knows!” the Prince T-shirt man says, grinning, pointing at Julie. “She really knows. I bet she knows all the songs. Do you?”

Julie smiles awkwardly, mumbles something non-committal, and lights a cigarette. She has that look that a lot of Prince fans have – a look that has hardened and intensified after his death. She looks as though she is carrying around a pleasant, private secret – as though she has been quietly told that heaven is real, that we’re all going there after we die, and that everything, no matter how dire it might seem, will be alright. She looks as though Prince wrote all that music just for her.

.@NPGUK #PrinceArmy flowers at Paisley Park. Beautiful #RIPPrince pic.twitter.com/OlTYG2Od1J

— Prince Watch (@PrinceWatchUK) May 14, 2016

Prince is private for a lot of people in that way. Although his fans are always eager to acknowledge that his music is universal – how else could you explain his record sales or his massive crossover appeal? – there is still something about him they feel the need to protect. They do not always reveal everything when interviewed; they always leave little gaps in their explanation. “I don’t know what I would have to say to you,” says one anonymous fan when I approach them for an interview. “I wouldn’t say anything except I love him and I always have. There is nothing else that I would say.”

Inside Cafe Lounge, Letteri is DJing. She is dressed as Apollonia, the co-star of Prince’s 1984 film Purple Rain. Letteri’s hair – long, dark – sits on her shoulders, and she dances with her hands screwed up into tight little balls that bob back and forth in circles around her head. It’s only early, so she is getting through the slightly more obscure cuts first, blasting the likes of 1986’s hidden gem ‘Anotherloverholenyohead’. A few people are up the front, dancing; over the next hour, their number will quadruple.

Letteri looks very happy. “I love it when I meet other Prince fans,” she had told me a few days earlier. “I love meeting people who have the same connection to him as I do. I feel as though his true fans really ‘get’ him. It’s this beautiful thing we all share – we just get what he was about and what he wanted us to all feel. He was this musical genius who made music that you couldn’t help but fall in love with.”

Letteri’s love story began at the tender age of nine. “The earliest memory I have of [falling in love with Prince] was at dance school. During class, the teacher was preparing us for a new routine and the song was ‘Cream’. Even though I was already familiar with Prince’s music at the time, that was the song that made me want to dig deeper into the rest of his discography.”

Admittedly, Letteri is a little unusual in that respect. A lot of Prince fans don’t have an origin story at all. Many admit – with a sense of disappointment – that there was no one point where they suddenly found themselves obsessed; no magic moment they can remember when that first spark of love caught.

Prade, for example, feels like Prince has always been there for her – as though he is as essential and commonplace as the oxygen she breathes. “I was born in 1978 so I was maybe four months old when his first album For You came out,” she explains. “My parents loved all types of music. I was just attached to Prince’s music for some reason. I always thought of him as a family member.”

Others simply heard his music in a restaurant, or were recommended a song by a friend. “I was first introduced to Prince in 1991,” says DeRousselle. “It was the release of Diamonds And Pearls that got me in. There was a show on BET called Video Soul that I watched nightly and I was instantly mesmerised by that song. It remains to this day one of my favourites.”

Of course, such stories are notable precisely for their ordinariness. That’s often the way it goes. When we fall deeply for musicians – when they become a part of us, something that we must physically carry – we can forget that from the outside, such adoration seems strikingly mundane. All the physical symptoms of our obsession seem passive and idle. Perhaps we buy the artist’s records, maybe we put them on at a party, or maybe talk about them a little too much over drinks.

But we don’t really do anything. We just listen. Nothing really changes when you fall for a musician, except of course, everything does; you never feel the same way ever again. Music just wanders into our life, requiring nothing but that we listen, and then sometimes – not always, but sometimes – it simply never leaves us.

Indeed, it’s that selfsame ordinariness that makes us do the things we do for our favourite musicians. Driven by the desire to prove our love to others, we tattoo ourselves in lyrics, wear branded shirts till they literally fall apart across our backs, travel miles and pay hundreds of dollars to attend shows – and we do it willingly.

So when it comes to Prince, it follows that fans have gone to all sorts of lengths in order to prove their love. Some, like Lloyd, pour hundreds of hours into moderating and curating online Facebook memorial pages. Some, like Lewis, scour Discogs and eBay, searching for The Purple One’s rarest test pressings and assorted shreds of memorabilia. And others, like DeRousselle, literally hand over their body to their idol, becoming breathing, walking tributes to him.

“I began embodying The Purple One shortly after his death,” DeRousselle says. “As a musician and performer I had already been covering his songs with my band. During the time of his passing I became increasingly inspired by him and devoted myself to bringing the passion and creativity of all that he created to my stage performances. The timing just seemed undeniably right.”

Two Paisley Park personnel told me to move on, like they were nervous about something. They didn’t know I was secretly praying in every room I walked in.

Then there’s Paisley Park. For Prince fans, the Minnesota estate is a kind of cultural Mecca. Getting there is its own ultimate test of faith – a way to definitively prove your willingness to sacrifice time, money and energy for your idol. Of all those the BRAG interviewed for this story, Prade was the only one who made the trip during his lifetime. It wasn’t easy, either.

“I was having financial problems at the time so I asked a bank to help me,” she says. But the bank did not see the purpose of granting a loan simply so a Prince fan could see the artist’s headquarters. It denied her request. “I remembered the lender telling me, ‘Oh, there’ll be another time, honey.’ I screamed, ‘No, there will not!’ I hung up and cried.”

Eventually, Prade’s husband and her mother managed to cobble together the money she needed to afford a full-blown Prince pilgrimage. She bought VIP tickets to two of his shows – consecutive nights on the Piano And A Microphone tour – return flights, rented a car, and set off for a “totally surreal experience”. It turned out to be one of the happiest weeks of her life.

It was snowing on the night of the first show. “I had never seen snow before,” Prade says. Inside the theatre lobby, she found herself surrounded by other Prince obsessives – all of them smiling at each other, chatting, sharing stories. Prade, feeling a little nervous, hung back and watched. “I have always been a people watcher,” she says. But even without joining in, she slowly started to feel something she had never felt before. “I listened to all the accents, watched what they wore and smiled to myself. I finally knew what it was like to be surrounded by people who loved Prince as much as I did.”

The shows were, as Prade had expected, magical. On the first night, she sat on a lavender pillow on the floor at the front of the stage; on the second, she hung around the back. “I saw his fro bounce up and down a few times, and saw his face when he got up,” she recalls. “But I am so short, mostly all I saw was his dangling feet stomping through his sets.”

Still, that was enough. More than enough, in fact. She cried (“More crying!” she admits, a little embarrassed), danced and sang. It was perfect.

The next day it was time for the tour of Paisley Park, the final stop on the pilgrimage. Led around by the guide – a fellow Prince fan who Prade had sometimes spoken to on the internet – she drank in every inch of the estate. She saw The Purple One’s twin studio spaces; the so-called Space Room where he would sit and watch television; his rehearsal rooms; and the long corridors he padded about in, dressed in his trademark purple bathrobe.

In each space, Prade waited back a little, letting the rest of the tour group walk ahead. Before long, she began attracting the attention of the guards. “Two Paisley Park personnel told me to move on, like they were nervous about something. They didn’t know I was secretly praying in every room I walked in. I was whispering prayers and thanking God for the opportunity of a lifetime.”

“I go out every night and sleep all day / Since you took your love away” – Prince, ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’

Cafe Lounge is filing up. A group of elderly women are sitting in the corner, bopping along and chatting happily. A tall, middle-aged woman is loudly singing along with the music, while her boyfriend flicks through his phone, head down, embarrassed. Letteri has moved onto the classics now – ‘Cream’, the song that started it all for her, makes an appearance, and a loud cheer goes up from the dancers at the front.

There are a few Prince T-shirts here and there, but the costumes don’t appear too complicated – that is, not until a nervous-looking man in his mid-20s enters, clad in a full-blown, handmade Prince outfit. He has gone to every conceivable end to make this costume; the detail is astonishing. He wears a headband pulled tight above his eyes, a thick purple coat, tight black pants. And there, perched on his thin, spotty neck, is an impossibly white silk ruff.

Everyone turns to look when he walks in. The man assesses the crowd, his girlfriend by his side, notices no one else has gone to half the effort he has, and turns a deep shade of red. He does not smile. For the rest of the night he sits over in the corner, out of sight, sipping beers and nodding awkwardly at all the people throwing him impressed nods.

He is, in many ways, what I had come to Cafe Lounge to see. Although I am a Prince fan – as committed and dedicated as some – I approached this article with embarrassingly cruel intentions. My aim from the outset was to go full Gonzo; to submerge myself in the insanity of fandom, to poke not-so-gentle fun at those who go to extreme lengths to honour their idols. I wanted to see a man in a Prince outfit get largely ignored by a crowd made awkward by his dedication; to see love for musicians gone kookily wrong and weird.

And I did this, apparently, without much self-awareness. Because I have never dressed up as Prince (to be perfectly honest, I doubt I could fit into tight enough pants) – because I have never cried on the phone to the bank while trying to raise the money to see the man in the flesh, because I have never tried to sing his songs, or set up a fanpage in his honour – I always assumed I was exempt from the weirdness of fandom.

I always assumed that my love was cleaner; more sensible; easier to bring up in polite conversation without embarrassing anyone. All I did was write about Prince. All I did was listen to those albums endlessly, till my records scratched and warped and I had to replace them, then replace them again.

But I was wrong. Fandom is, by its very definition, extreme. It makes us do mad things – it consumes us, and it makes us blissfully ignorant when it comes to the judgement of others. It makes us hang back in rooms we are not meant to hang back in and say a prayer to God for letting us get so close to a man who doesn’t even know that we exist. It makes us cry, again and again and again, because a complete stranger has been taken from us. It makes us mournful and it makes us strange.

And it is, in that way, and for precisely that reason, beautiful. That is what we talk about when we talk about Prince. We’re not talking about the man, or his music.

We are talking about that odd, deeply private thing that connects a room full of people in a bar on a Friday night, all of them listening to the voice of a man they have lost from their lives. We are talking about the thing that we cannot put to words – the thing that makes us turn away prying journalists, convinced that not everyone will understand us. We are talking about connection – and not connection to a song like ‘Cream’, or to a stranger on the front cover of an album we have poured over since we were 11. When we talk about Prince, we are talking about connection to each other.

Letteri is onto the good stuff – the songs everybody knows; songs that everyone has heard a thousand times, full of lyrics so oft-repeated that they are seared onto the tongue. The room is packed with dancers. Letteri is still bopping along, her hands still up near her ears, moving back and forth.

The man in the Prince outfit gets up to grab a drink, and passes through the thronged circle of dancers. They part for him, cheering. And he turns, nodding, a deep, embarrassed smile cut into his face, offsetting the fading crimson in his cheeks.