Throughout the history of electronic music, women have been grossly under-represented in performance, production and management. Whether it’s in music studios, media and PR agencies, A&R and record labels, right through to their practice as performers, participants or spectators, women’s opinions continue to be held in contempt or treated with suspicion.

This stigma is perpetuated in two ways. Overtly, it’s a matter of direct and deliberate discrimination – from the off-hand ignorance and petty drivel that populates the thin veil of social media, to the music industry’s habit of sexualising its female stars. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, opportunities are withheld: the imbalance is self-evident in the poor rates of representation of women in festival lineups, and in the antagonism that simmers in music studios.

In 2017, history and gender politics continue to inform the under-representation of women in the electronic music industry. But certain local communities are helping to recognise and overcome these issues. There is great work being done in Australia; real change being enacted through the power of community and awareness.

Electronic music and its now well-documented history has long been tied in with adversity and politics. The genre was born from excluded and marginalised minorities seeking an inclusive and welcoming environment, free of prejudice against sexual orientation and gender identities.

But if the celebratory notion of inclusion is fundamentally ingrained in electronic music, why have we left the women behind?

The recent history of women in music: what the statistics say

The last couple of years have seen a dramatic and refreshing increase in the attention afforded to the under-representation of women in electronic music, both in Australia and internationally. Several popular music media outlets have contributed to an ongoing narrative that, for the most part, has centred on statistics to outline the gravity of the issue.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

In 2015, international women’s collective female:pressure published a widely circulated report on the alarmingly low ratio of women to men on major festival lineups and record label rosters. A number of other publications, including Vice’s Thump, lent their voices to the debate, with a steady stream of articles that for the most part addressed these statistical imbalances without delving much below the surface.

Elsewhere, mainstream electronic music outlets like DJ Mag were rightly pulled up on their lists of “Top 100 DJs” that variously featured few to no women at all.

On a local level, triple j’s Hack and the Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) published a crucial analysis of the disparity in gender representation at various levels of performance and participation in Australia’s music industry. A more recent international study can be found here.

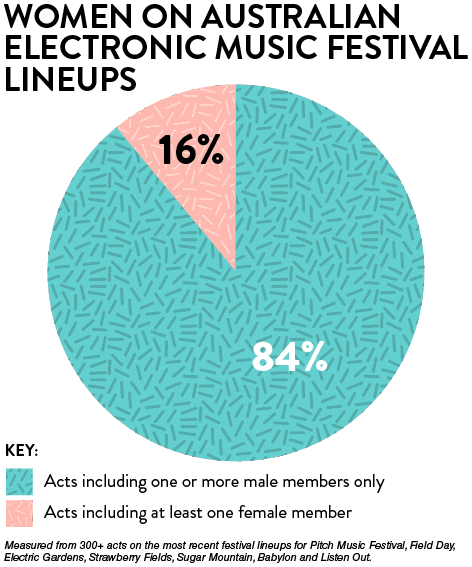

To prepare this article, the BRAG conducted its own statistical study of seven of Australia’s most visible and popular electronic music festivals – those with at least ten artists on the lineup, and at least 50 per cent of their artists performing some form of electronic music.

Those festivals chosen included Pitch Music Festival, Field Day, Electric Gardens, Strawberry Fields, Sugar Mountain, Babylon and Listen Out, and only their most recent incarnations were considered.

(Tara Benney, a Strawberry Fields director, has publicly commented on the festival’s gender ratio here.)

The results are far from positive when it comes to these festivals’ representation of women. Of the 300+ acts featured across these lineups, only 51 included a female performer. A number of the festivals fared very poorly indeed. Women were represented in a meagre 16 per cent of the total acts, echoing the trends identified in the female:pressure and Thump studies, among others conducted in recent years.

What does collating these statistics actually achieve? Well, we ultimately use these numbers to open a dialogue, increase awareness, and seek accountability for an imbalanced status quo.

Statistics, of course, only tell one part of the story – and for that reason, the festival-specific results are not published here (though all the lineup details are freely available online). Resolving the inequality of representation on festival lineups would require a 50/50 balance of men and women. But while such a goal might indicate numerical equality, it’s not the be-all and end-all. What women in music really need is equality of opportunity.

It’s very easy to point fingers at promoters, but we must also recognise the tremendous amount of work involved in selecting and approaching artists, who may themselves have scheduling conflicts or are not interested in travelling to the other side of the world. What’s more problematic is how the gender disparity is continuously seen and felt at multiple levels: artist representation at festivals is but one very visible tier of a complex issue.

Absence and (in)visibility: the gaping hole in Australian music

“The institutionalized practices of excluding women from the ideological work of society are the reason we have a history constructed largely from the perspective of men, and largely about men.” – Dorothy E. Smith, The Everyday World As Problematic: A Feminist Sociology

“Everything is political. All of our social relations are based on economic and therefore political power. It amuses me when people say it’s inappropriate to combine politics and music … Everything about this industry is based on politics.” Jim Poe, Bondi Beach Radio

When we consider the visibility of an individual – be it a musician, manager, promoter, label employee, or any of the countless roles within the broad umbrella of the music industry – what exactly are we referring to?

Visibility is the opportunity that we afford to an individual – whether that’s the opportunity to succeed or the opportunity to fail. Visibility is in validation of opinion and character. Visibility is the establishment of an inclusive, mutual history. Visibility is in leadership. Visibility is in exposure and recognition, respectful of orientation and identity. Visibility is in education and encouragement, and in the breaking down of gender- and identity-prescribed expectations.

The history of popular music, let alone electronic music, has been largely established through an exclusionary patriarchal lens. It’s telling, then, that the conversation surrounding women in the music industry often revolves around absence or invisibility. Ours is a history in which women have traditionally struggled to be recognised for their work in a male-dominated industry, remaining codified in representations of gender that have been traditionally ascribed by male privilege.

Female musicians are always ‘female’ guitarists, ‘female’ drummers … It’s one of those little things that undermines female artists.

This history has been passed down and perpetuated through generations. It is germinated through language and through the spaces that we inhabit and occupy. It permeates through our daily dialogue and rhetoric. If we remain apathetic or resistant to acknowledging this history, we are ultimately reinforcing the traditional tropes and constructs of gender identity that constitute it.

All too easily we encounter entrenched attitudes, systems and expectations that impact directly on the visibility of women in the music industry. From the BRAG’s discussions with individuals and groups involved at various levels of music performance and management, there appears to be a totally unreasonable expectation that women walk into the music industry as fully formed, fully fledged professionals, or that their very interest or participation in the music industry carries its own sense of privilege or tokenism (an especially disgusting thought).

The effects of exclusion are both insidious and conspicuous. Exclusion directly affects the individual – in the conception, realisation and production of their music – and the community, in enabling and incorporating said music. Consigning women to a sense of ‘otherness’ in all aspects of the music industry undermines their visibility and dilutes their history. Limited opportunity limits not only individual and collective expression; it is felt in the relative lack of role models and mentors for others to aspire to and be inspired by.

Kristen Marconi, the founder of Australian music community Let The People Dance, says: “With most industries being male at the top, for girls to start being that role model or take that chance, they often need to be willing to be the first or only girl in the room.”

Visibility is effected in projection, image and branding. We’re all familiar enough with the narrative now to appreciate that, historically, the marketability of men and women has often stood in stark opposition. It’s not often a press release or Facebook page describes someone as a “male DJ”, nor does image seem to figure in negative terms when we consider male performers.

“Female musicians are always ‘female’ guitarists, ‘female’ drummers… you would never say that is a wicked ‘male’ bass player,” says Jen Finnley from Pink Noise. “Our gender always seems to precede. It’s one of those little things that undermines female artists”.

Vested commercial interests are most obviously present in the damaging extremes of the vast and bloated EDM market, which often centres on the marketability of a DJ or performer: a sexualised commodity redacted of meaningful political significance and, ultimately, a regressive influence on our progress towards equity and equality.

The politics of space: the physical oppression of women

“Everything that a guy says once, you have to say five times.” – Björk, Pitchfork

“Feminist and cultural studies scholars alike agree that technology is not inherently masculine, but has been labeled as such … such influences have narrowed the definition of what constitutes technology and systematically written women out of technology’s collective memory.” – Rebekah Farrugia, Beyond The Dance Floor: Female DJs, Technology, And Electronic Dance Music Culture

The discussion of women in electronic music cannot be separated from its politics. Whether or not we actively identify ourselves as political, our actions are inherently political. We are, over the course of our everyday lives, privy to a plethora of language and behaviour that is situated in a political discourse. We experience it in the spaces we occupy, in the concerts we attend, the music we listen to in transit, and the language we use.

“Creating art or using your voice in a public space is inherently political,” says Pink Noise’s Mari Stuart. “It’s up to each person to decide what they want to do with that voice, and obviously every situation is different, but for me it’s important to speak against and not perpetuate systems of oppression when I’m given the opportunity.”

The politics of language and of space play an important role in the disempowerment and invisibility of women. Established spaces such as the recording studio, its instruments and its technologies, have long been dominated by the masculine presence. As sites of male-pioneered leadership and power, they often reinforced traditional gendered divisions of labour. This is a space in which women have been kept largely absent, or their pioneering role obscured from history.

One of the most common examples is that of musician and composer Delia Derbyshire, who exerted a tremendous and, until recently, largely invisible influence on popular culture through her work on the theme to Doctor Who (with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop). But overemphasis and fetishisation of such iconic figures and “presenting them as oddities and exceptions to the rules of their times” generates its own problems, argued Abi Bliss in The Wire. Such a practice “risks banishing them to their own special glass cases, away from the main exhibits in the museum of musical history”.

Our oppressive history is also present in the sharing of information. Behaviours intrinsic to DJing and community-building, such as crate-digging in record stores, are characterised by the author Rebekah Farrugia as “male-dominated spaces [that] became central hubs where knowledge was shared and social networks developed”.

The politics of language: how we talk about women in music

Let’s consider a few everyday examples of the pervasive ignorance that language can carry:

“If people like your music, you’ll become successful no matter your gender.”

“If women really want it, they should work for recognition like the rest of us.”

“Why should I pay more attention to her work because she’s a woman?”

Statements such as these are reductive in any number of ways. They presuppose a non-existent universal judgement of merit that reinforces the insidious nature of oppression. They deliberately obscure the underlying principles of power in place and invalidate the struggles many women experience. Read the comments on just about any major news piece on women in music and you’ll come across this sort of passive-aggressive discourse.

Just because it isn’t happening to you, or you haven’t noticed it – or would prefer not to – doesn’t mean it’s not there.

Bondi Beach Radio’s Jim Poe is well aware of the political power of language. “When I interview female DJs or musicians on my show or for an article, I never bring up their gender,” he says. “I think you can recognise that, you can celebrate their achievements and give them a platform, but you have to let them decide how and when to discuss it.”

https://soundcloud.com/cassette/cassette-afrikaburn-2017

During discussions with women involved in the electronic music industry, the BRAG raised the topic of feminism as a legitimate point of empowerment. Some interview subjects met the issue with reluctance.

“Personally I don’t like the word ‘feminist’ as I feel it can have aggressive or misunderstood connotations,” says DJ and producer Cassette. “We can all help each other if we work together. The market wants diversity more than ever right now, so of course it would be foolish for anyone in the business of entertainment to ignore that.”

Among these negative connotations of feminism is the impression or perception of being victimised by “the oppressive, patriarchal gender politics that continue to impact everyday life for women in a Western context, despite the progress that has been made and rhetoric that argues otherwise,” according to Farrugia.

Given the fact that club spaces, studios, A&R, and just about every other facet of the music industry remains dominated by the masculine presence, identifying with feminism might serve to alienate or distance women further. Of the BRAG’s interviewees, however, the vast majority saw identifying with feminism as a positive and empowering vehicle that actively works against perpetuating systems of oppression.

And of course, we must consider our own use of language. This article is couched in gendered phrases like ‘woman’, ‘women’, ‘men’ and so on; not strictly in oppositional terms, but in referring to the underlying and inherent gender dynamics endemic in much Western cultural discourse. Ultimately we need to consider this as a universal series of issues rather than constantly locating it in a gender identity.

Finding voice and visibility: the way forward for women in music

How do we address the under-representation of women in electronic music in a meaningful way?

First, let’s talk about it. Let’s make these issues tangible and present in our everyday consciousness. The more these issues are identified and discussed, the more they enter our popular lexicon and gain social capital and exposure. Visibility and participation increases social awareness and influence. Simple conversation will make a great difference in dismantling an oppressive history and forging a diverse, inclusive and respectful future. In the words of WA artist Kučka,“The more that people think and talk about these issues, the more progress we can make.”

Music has a resonance unlike any other creative pursuit, and musicians have the extraordinary potential to be drivers and promoters of change and awareness. Many of popular music’s most successful examples of this are women: think of Björk, Grimes, Rihanna, Lorde and Beyoncé. They’re among the more obvious examples of role models who young women and men can aspire to, many of them having publicly acknowledged the inherent misogyny and sexism that undermines a meaningful and inclusive creative society.

And the way in which our means of communication has changed cannot be understated here, either. The internet, for all its vitriol, is a fundamental, accessible avenue in generating dialogue and bringing women – and people in general – together. The importance of community-building is absolutely paramount in promoting awareness and generating a positive, inclusive and empowering environment.

From there follows the equality of opportunity in our creative spaces. “Giving opportunities to young artists to perform and grow in their art is super important as we try and balance the disparity in the industry at the moment,” says radio show host and DJ Andy Garvey.

Poe agrees. “That immediate experience of enjoying music and having fun together starts to do away with people’s prejudices. I’m not saying it smashes patriarchy in and of itself, but a banging Claire Morgan set, for example, might create a space for a young guy, for example, to start to get over his prejudices.”

Australia is very fortunate to have such a strong and burgeoning local network of passionate young people who are working towards dismantling traditional systems of power and gendered expectations and establishing connections. Already, we have real grassroots role models who are generating change and disrupting the conservative disease that plagues progression.

It’s also important for us as a universal community to call out sexism and discrimination when it comes up.

Local communities such as Pink Noise’s radio show and mixtape series, Gail Priest’s Audible Women directory, Melbourne-based Synth Babe Records, the ListenListenListen community, Marconi’s Let The People Dance and The Ladies Network are invaluable examples of such group initiatives, among many others.

FBi Radio’s Dance Class program is an essential initiative to foster, train, mentor, promote and educate female dance music lovers, with input and mentoring from some fantastic, highly experienced women in the industry including Garvey, Adi Toohey and Kali Picnic.

To its credit, Smirnoff has also initiated an awareness campaign, Equalizing Music, in tandem with DJ The Black Madonna and DJ Rachael. It seeks to actively address the low numbers of women visibly involved in the music industry, and aims to double female headliners at major music festivals in the next three years.

Another forthright approach is the organisation of female-only lineups and events; something Pink Noise has been particularly involved with. “For now, it is really empowering to have all-female lineups because we all need to reach a point where we are supporting each other where we have not been supported in the past,” says Marisa Marsionis.

But it’s also important for us as a universal community to call out sexism and discrimination when it comes up. Pitchfork’s Philip Sherburne focused his ire in a direct comment on EDM’s inherent reduction of women to a consumable product. And in one local example, a FasterLouder article from last year addressed the disgustingly-titled ‘Tits Out For The Boys’ by none other than days-of-yonder Australian producer Nick Skitz. This baseless and primitive appeal to back-slapping hypermasculine larrikinism should be discouraged and criticised so that a social precedent is set.

And what about those music festival lineups? “I think Australian media recognises the demand for diversity in the industry, but it may take longer for promoters to reflect this in their lineups,” says Cassette. “I guess for this to happen, local promoters would need to look outside their immediate friend circles and get a bit more creative with their lineups, taking chances on suitable female talent where they can. Ultimately it will only benefit them, as there is market demand for it.”

In Marconi’s view, it’s a matter of “people coming together and supporting and nurturing women to try and put themselves forward. We need to be extra welcoming and encouraging … If we want more diversity, togetherness and unity in this industry, we all need to do more to help women feel safe in trying.”

—

There’s a fabulous Women In Electronic Music Masterclasses program taking place this Saturday June 17 down in Marrickville, where you will get hands-on experience and training from a wealth of industry specialists, musicians, and producers. Jump on Facebook to take part. Later that day, and following on from the Masterclasses, is this year’s Women In Electronic Music Showcase, which is going down at the Oxford Art Factory, with a diverse and very talented array of women performing in what promises to be a wonderful night.