Taking place over a two day span, killing an estimated 300 and injuring over 800 African Americans, the Tulsa Race Massacre stands as a moment in history that many have never even heard about, including those born and raised in the great city of Tulsa.

Swept under the rug of history, the Tulsa Race Massacre is an incident in time that has been in the shadows for nearly a century, and widely unknown to many Oklahomans, despite its occurrence in the second largest city within the state.

Despite the education system having an Oklahoma History course in place as a requirement throughout secondary education, the vicious massacre that occurred 99 years ago is widely untaught in school, rarely mentioned in textbooks, and has only come into the light once again in the past decade as Tulsa tries to reconcile with the horrors that happened.

As the Black Lives Matter movement marches on, events that have been purposefully kept out of the lime light are now being brought to life, with the sole purpose of educating others, and moving on from these moments in history with a better understanding of why we must protect races that some profile against.

To learn about this horrific mark in history, one must first learn about the booming town Tulsa had in the 1920s, and how it was reduced to ashes over the span of two short days due to an alleged incident that changed the course for African Americans in the city forever.

1921 was showing to be a great year for Tulsa. Although caucasians and African Americans were largely segregated, with their dwellings split by the town’s railroad line, each race had their own safe haven, bursting at the seams with opportunity far and wide.

While Tulsa bustled on in the oil industry, the African American side of Tulsa was dubbed Greenwood – a metropolis for black Tulsans where they could live, work, and spend time in recreation, all while travelling to work in white Tulsa.

At the time, Greenwood was also named Black Wall Street, being noted at the time for being the wealthiest black community in all of the United States. The town not only had their own area to live freely within, but held several business and services own by the black residents including movie theatres, nightclubs, churches, grocers, and many professional services to ensure Greenwood was a refuge.

However, a two-day massacre occurring diminished this thriving community to smoking rubble, causing many who called Greenwood home to be killed or injured.

May 30th, 1921 marks itself as the beginning of a riot that Tulsa still hasn’t recovered from to this day.

The alleged incident that sparked the riot stemmed from an encounter between a white elevator operator named Sarah Page and a black resident of Greenwood, Dick Rowland, who worked as shoeshiner, which took place around 4PM in the Drexel Building in white Tulsa.

Although Rowland worked at a shoeshine parlour, he entered the Drexel Building on Main Street to use the top-floor toilet which was only available to African Americans. As he took the elevator to the top floor, the operator on hand, 17-year-old Page, emitted what was heard as a scream where witnesses allegedly saw Rowland rushing from the building.

Even though it is widely unknown what actually occurred in the elevator, a clerk from the clothing store Renberg’s, located on the first-floor of the Drexel building, found Page in what he noted to be a distraught state and decided to summon the authorities on the thought that Page may have been assaulted.

To this day, no one is certain of the encounter Page and Rowland had, although many presume that they might have known one another as Rowland would have regularly taken the elevator to use the top-floor toilet.

While witnesses assumed an assault occurred, many speculate that Rowland could have simply tripped and tried to steady himself against Page causing her to panic, or that they possibly were lovers in the midst of a quarrel.

Whichever scenario occurred, the incident is shrouded in mystery, but many who were close to Rowland pleaded that he was never capable of assaulting or raping Page.

Even though Page likely was questioned by the authorities regarding her statement, her words have been lost to history, although it is known that she told the police that she didn’t intend to press charges against Rowland.

Without charges being pressed, Rowland still feared for his life being a black man accused of assaulting a white woman, therefore he fled to his mother’s home in Greenwood, hoping to stay safe amongst the madness that was soon to occur.

May 31st, the following morning after the incident between Page and Rowland, white Detective Henry Carmichael and black Patrolman Henry C. Pack located Rowland, taking him into custody at the Tulsa City Jail, only a few blocks away from the Drexel building.

Shortly after, Police Commissioner J.M. Adkison noted that he’d received a call from an anonymous person threatening against Rowland’s life, which subsequently caused him to be moved to the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse.

The moment that brought this incident to attention began when one of the two white-owned newspapers, Tulsa Tribune, penned an article with the headline “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator.”

Many witnesses have also stated that the Tulsa Tribune also included an editorial titled “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” Yet again another piece of the puzzle lost to history, as all original copies of the newspaper have, apparently, been destroyed, while the microfilm copies have the pages of the two fire-sparking articles missing.

Once the afternoon edition of the Tulsa Tribune hit sales racks on May 31st, the news of the incident spread like wildfire, enticing many white Tulsans to hone in on the potential lynching of Rowland.

By 4PM, white residents began their march towards the Tulsa County Courthouse, where several hundred gathered by sunset around 7:30PM, and sheriff Willard M. McCullough was forced to organise his deputies around Rowland in a matter of protection.

Less than an hour later, three white men forced their way into the courthouse, making demands that Rowland should be turned over to them, which Sheriff McCullough bluntly refused.

On the other side of the railroad tracks, members of Greenwood gathered to discuss the situation that was quickly bubbling up to boiling point. Quickly, many residents of Greenwood prepared for a fight by collecting guns and ammunition, determined to prevent Rowland from being lynched by the ever-growing crowd in front of the courthouse.

Around 9:30PM that night, approximately 50-60 armed members of Greenwood arrived at the courthouse to support authorities in defending Rowland from the large mob, which alarmed the whites who had gathered, causing over 1,000 of them to take up arms themselves while the crowd swelled to nearly 2,000 in an angry mob.

Tensions rose as rumours began to spread throughout Greenwood that whites were storming the courthouse, determined to lynch Rowland, where a second alleged incident occurred: a white man ordered a black man to surrender his firearm. When the black man refused, the white man shot him. Whether accidental, or serving as a warning, this second alleged incident served as even more fuel for the fire.

After those initial gunshots, the riot began by whites in the crowd firing their guns at the blacks in the crowd, bringing the white mob to infiltrate Greenwood, looting stores and causing structural damage along the way.

As panic set in, the large white mob began firing their weapons at any African Americans they set their eyes on, while additionally killing at least one of their own race in the mass confusion that ensued.

With chaos surrounding the entire town of Greenwood, the National Guard organised a plan to subdue rioters, deploying several members to calm the calamity around the town, while rounding up numerous persons of colour for detention.

Midnight closed in, and white rioters resumed their post outside of the courthouse, shouting their support for a public lynching of Rowland, all the while attempting to storm the building.

Throughout the night, and into the early hours, shots between the white and black crowds increased, with rumours flying rampant of trains arriving with more blacks to help reduce the white mob.

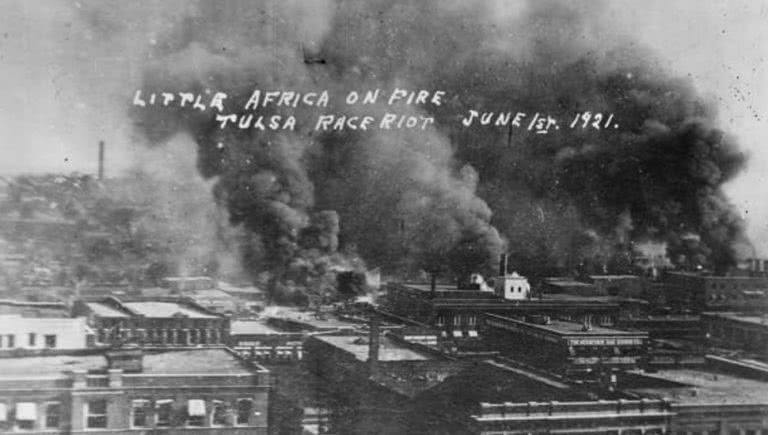

As tensions peaked, many whites crossed over the railroad tracks to enter Greenwood, throwing oil-soaked rags that were lit on fire into numerous businesses and residencies across Archer Street in Greenwood. Although the Tulsa Fire Department attempted to stop the fire damage, they were met with gunpoint from the white mob that intended for “little Africa” to burn.

“It would mean a fireman’s life to turn a stream of water on one of those negro buildings. They shot at us all morning when we were trying to do something but none of my men were hit. There is not a chance in the world to get through that mob into the negro district,” witness Scott Elsworth stated.

By 4AM, around two dozen businesses in Greenwood had been set on fire, with whites intent that they burn to the ground, and by 5AM, a full-blown riot had broken out.

At the break of dawn, a train whistle blew across Tulsa, and many rioters took it as a signal to launch an entire assault in Greenwood, which ignited the riot even further, causing the ever-growing white mob to pour into Greenwood, looting homes and businesses, forcing residents out of their home, and causing more damage than ever.

As rumours continued to spread that black Tulsans had a built up armoury of weapons that they intended to use on the whites, the whites kicked things off by attacking by the air, where numerous eyewitnesses noted that airplanes controlled by whites dropped firebombs on Greenwood, where law enforcement later stated that these planes were intended to protect Tulsa against a “negro uprising.”

Eyewitness Buck Colbert Franklin explained:

“Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes – now a dozen or more in number – still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.

“Planes circling in mid-air: They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top.

“The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught fire from the top.

“I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?'”

As the fires raged on in Greenwood, the Oklahoma National Guard was deployed with 109 troops to calm the storm that had occurred. When they arrived, martial law was declared, and the aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre began.

To this day, the number of deaths that occurred as a result of the Tulsa Race Massacre widely varies, and is entirely unknown. Although the newspaper that originally caused the riot to spark listed that nine whites and 68 blacks had perished, it’s been disputed that anywhere from 176 to 300 people had died, while also listing injuries at over 800.

Furthermore, the vast majority of Greenwood was reduced to rubble. The losses caused a staggering 10,000 persons of colour to become homeless, destroyed 191 businesses, the only hospital within Greenwood, 1,256 homes to be burned down, and caused an estimated $750,000 in structural damages, equatable to $32 million today.

Although former mayor of Tulsa Judge J. Martin stated a plan of rehabilitation, and a promise of funding, many citizens of Greenwood spent the winter of 1921-1922 in shabby tents.

“Tulsa can only redeem herself from the country-wide shame and humiliation into which she is today plunged by complete restitution and rehabilitation of the destroyed black belt. The rest of the United States must know that the real citizenship of Tulsa weeps at this unspeakable crime and will make good the damage, so far as it can be done, to the last penny.”

Soon after this was stated, a small group of white developers pressed their influence by having the city pass a fire ordinance to prohibit Greenwood from being rebuilt. Luckily, the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled this as unconstitutional, but many of the promised funding was never raised for the residents of Greenwood.

After these failed attempts to bring dignity back to Greenwood residents, Tulsa city planners took action to utilise the zone for public works, constructing the new Tulsa Union Depot across a section of Greenwood less than two years after the Tulsa Race Massacre occurred.

Even though this moment in history marked itself as one of the largest acts of violence that Tulsa has ever seen, the years and decades that followed this horrific massacre remained brushed under the rug, with numerous court cases being dismissed, and people kept in the dark about what had happened in Tulsa.

There were never any charges related to the riot, and it was largely omitted from history books, newspapers, curriculum, and reports.

On the riot’s 75th anniversary, attention was finally brought to this despicable moment in Tulsa’s history by the Oklahoma Commission setting out to investigate the Tulsa Race Massacre by conducting interviews, hearing testimony, and arranging ground surveying to find a final account on how many perished in the riot, of which many believe there is an unknown mass grave of victims.

In 2001, 118 of the known survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre were given a gold-plated medal to mark the moment the survived through in history.

Additionally, mayor Kathy Taylor publicly apologised to survivors, while governor Keating signed the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act, acknowledging the event in history, creating scholarships for Greenwood resident descendants, and creating the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park in 2010 as a memorial for those who died in the riot in Greenwood.

Now, as the Tulsa Race Massacre reaches its 100th anniversary, Oklahoma schools are finally recognising that the riot marks an important time in history that needs to be taught, lest we repeat the past.

An extensive curriculum has been provided to the school districts so that generations to come are aware of the dark secret Tulsa holds, and to prove to future Tulsa residents that even though racism once stood proud in Oklahoma, that it has no place there today.

In a town where the repercussions of a riot that happened nearly a century still boldly stand out, where the white side of Tulsa on one side of the railroad thrives with towering skyscrapers, while the other side of the railroad still is marked with houseless cement porches from where Greenwood residencies once stood, a moment still marked on the face of Tulsa shouldn’t be one that is kept out of the public eye.