“Lovelessness is a boon to consumerism.” – bell hooks, All About Love.

The Match Group, an international conglomerate that owns Tinder, OkCupid, and Plenty Of Fish is a sheer force of nature. So it’s helpful, given the company’s ever-growing commercial interest in algorithm development and data mining, to contemplate how their sites participate in – as opposed to simply reflect – the ebbs and flows of intimacy, connection, and romantic and sexual interaction. And how an increasing, overbearing presence of capitalistic ideology within our love and sex lives might impact on our relationships.

The overwhelming and ever-growing reach of corporate tech giants Google, Amazon, and Facebook has led former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris to note that “a handful of people working at a handful of tech companies steer the thoughts of billions of people every day.” And Tinder only continues to grow. It currently claims to instigate “one million dates per week”, “1.6 billion swipes per day”, and is used in over 190 countries.

In what’s often deemed ‘the sexual marketplace’, we’re currently seeing a growing desire for instant gratification. “Fixating on wants and needs, which consumerism encourages us to do, promotes a psychological state of endless craving,” writes activist and visionary bell hooks in her book, All About Love: New Visions. “Advertising is one of the cultural mediums that has most sanctioned lying. Keeping people in a constant state of lack, in perpetual desire, strengthens the marketplace economy.”

Similar to Facebook’s predecessor Facemash – an interactive website built by Zuckerberg where users rated the attractiveness of women on his campus – Tinder co-founder Sean Rad said in Time Magazine in 2014, “We always saw Tinder, the interface, as a game.”

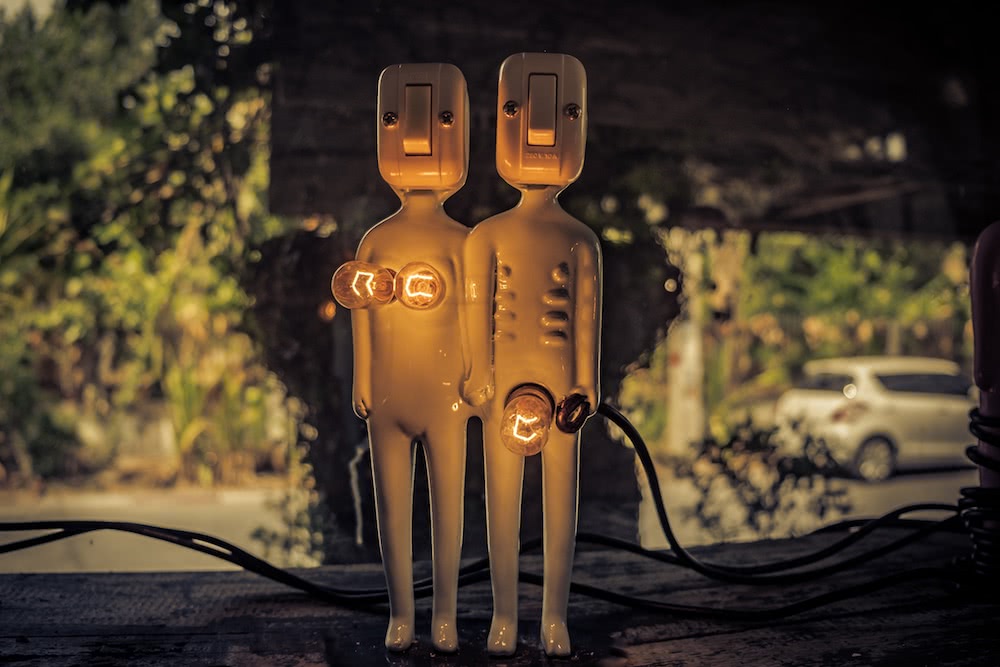

Image: Anna Sastre

Tinder uses an ELO-desirability score. Some profiles are ranked higher than others, all in a bid to connect users its algorithms (and therefore, the algorithm’s designers) believe are in the same league. According to Tinder data analyst Chris Dumler, “Every swipe is in a way casting a vote.”

According to New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino, “sexual value continues to accrue to abled over disabled, cis over trans, thin over fat, tall over short, white over non-white, rich over poor.” If existing widespread oppressive beliefs about the sexual worth of minorities are instilled into Tinder through a voting system, surely there should be interventions put in place to ensure these algorithms don’t discriminate against its users.

Tinder is yet to include non-binary genders on sign up, and automatically assumes that women are attracted to men, and vice versa. In Doing It: Women Tell The Truth About Great Sex, Melbourne writer Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen includes a quote from one of her interviewees. “when you are seen, when you are included, you have more agency – you have more power.”

Tinder only continues to grow. It currently claims to instigate ‘one million dates per week’, ‘1.6 billion swipes per day’ and is used in over 190 countries.

In late 2017, French journalist Judith Duportail went to extreme lengths to gain access to her Tinder data. Enlisting a privacy expert and a human rights lawyer, she eventually received 800 pages back from the company, and was shocked to learn that Tinder knows everything from the race of the person you’re most likely to match with to the average amount of time someone spends on your picture before they swipe.

Luke Stark, a digital technology sociologist at Dartmouth University, writes in Durportail’s article, “Apps such as Tinder are taking advantage of a simple emotional phenomenon; we can’t feel data. This is why seeing everything printed strikes you. We are physical creatures. We need materiality.”

Image: Christopher Campbell

In a bid to become more transparent, this year Tinder responded to changing EU privacy laws by allowing anyone access to their data with the click of a button. Unlike Duportail’s experience, reading my own 33-pages of data was underwhelming. It might be a mark of my generation, but I don’t think much of Tinder or other companies selling my images or my (often stunted) flirtations via the app. It feels too distant; too obscure for me to fully realise the societal cost of my information being sold to third party advertisers.

These transactions feel invisible, almost inexistent. The potential reward of “finding” romantic intimacy is more tempting, overshadowing the risk of contributing information – and therefore power – to various companies that may impact our future.

And even though Tinder claims it is becoming more transparent, their matching tools are integral to their intellectual property – meaning they have no responsibility to disclose exactly how their algorithms are designed or the logic that they’re built on.

In Duportail’s article for The Guardian, privacy activist Paul-Olivier Dehave writes, “We are leaning towards an even more intangible world where data collected about you will decide even larger facets of your life. Eventually, your whole existence will be affected.” And while this might seem like a conspiracy theory or the foundations for an episode of Black Mirror, social control systems built off the back of data collection aren’t as far off as they seem.

Tinder ranks some profiles higher than others, all in a bid to connect users its algorithms believe are in the same league.

In China, a ‘social credit’ system that uses the collation of data on its citizens is being planned for integration by the government in 2020. In ‘Dockless Bikes, Data-Capitalism’, PhD student and sessional academic Nikolas Ozolins examines how dockless bikes have been used to survey the movements of citizens by major corps, writing that the data gained for this system will be “used to assign individuals a number that represents their ‘trustworthiness’”. People with low scores will have restrictions placed on them, including on their freedom to travel.” And he says with Australia’s recent Identity-matching Services Bill 2018, we could potentially be heading in a similar direction.

Image: Annie Spratt

This year, London academic Laura Thompson published I Can Be Your Tinder Nightmare, a revealing – albeit somewhat terrifying – body of research that unpacked the intention behind men’s explicit misogynistic harassment within online dating.

Analysing 526 messaging exchanges collected and posted by curated Instagram accounts Bye Felipe and Tinder Nightmares, she found that these men’s abusive reactions to rejection or being ignored were often an attempt to discipline women who’ve been granted access to power over the last century.

Thompson writes that these men, knowingly or not, are attempting to “reposition women and femininity as sexually subordinate to masculinity and men.” While this form of oppressive behaviour is mostly an extension of power structures that enable violence against minorities, she writes that these apps and websites “provide the social tools for [misogynistic behaviour] to flourish.

“Looking at Bye Felipe, it’s just the sheer amount and the repetition of it – it’s quite arresting I think. Especially some of the quite violent ones and rape threat ones,” explains Thompson over Skype. These messages all seem to all use a similar rhetoric, indicating these reactions are affirmed and seen as rational reactions from within their online social bubbles.

“That’s why I wrote that paper – to pull apart the themes of different discourses that they’re pulling on, because they haven’t just popped out of nowhere. It hasn’t just suddenly come along because Tinder is now a thing. They’re pulling on some quite old sexist tropes and ideas: you know, the figure of the slut, for example,” explains Thompson.

This disciplinary behaviour can be found in a more sinister movement: incels (self-described “involuntary celibates”). This year in Toronto, Alek Minassian called for an “Incel Rebellion” and massacred ten people while injuring another 16. And he isn’t the first to respond to his perceived sexual rejections in a murderous rage.

At the core, incels are entitled and self-victimising. They direct vile and dehumanising hatred at the same women they desire. They believe sex is about dominance, rather than a mutual, creative giving and receiving of pleasure. The New York Times’ Amanda Taub asserted that the incel mentality speaks to “broader resentments” among men in the West in response to shifting gender politics post Me Too movement, sexual revolutions, and self-esteem movements and online dating, which have given women more choice.

Image: Charles Deluvio

Thompson writes in I Can Be Your Tinder Nightmare that the men in her study “depict the dating app as a transactional space for sex where women are to be used as a ‘‘free’’ source of sex.” And Nguyen asserts that online dating has exasperated a sense of disposability, explaining that, “some online daters fail to understand that casual sex is not mutually exclusive with respect.”

In an article for The Guardian, Rebecca Solnit writes, “Despite half a century of feminist reform and revolution, sex is still often understood through the models capitalism provides. Sex is a transaction … it is not imagined as something two people do that might be affectionate and playful and collaborative, but that one person gets.”

Asked what Laura Thompson thinks the consequences are for having a capitalist framework for viewing people as a marketed product to consume, she says, “You hear of all these bad behaviours – you know ghosting, bread crumbing – we have all these terms now for all these basically crappy things that people do to each other whilst dating.

“And I’m sure that these less than ideal ways of relating to other people have always existed and have always been to some extent in a dating landscape, but it does seem more common. There’s less incentive really to treat people decently if you’ve got lots of other different options and you can just get back on Tinder and keep looking,” she says.

Tinder knows everything from the race of the person you’re most likely to match with to the average amount of time someone spends on your picture before they swipe.

“People seem to be really terrified of intimacy,” Thompson says of her interviews with women. “Dating’s really difficult.” She laughs. “If you can just toss people off and you don’t have to get too emotionally involved with anyone, then you keep yourself a bit more protected I guess.”

While collective changes in Western folk’s relationship towards intimacy are hard to measure, Thompson believes social and economic changes over the last few decades could have had an effect; from small communities becoming fewer and far between, to people increasingly moving for work. “People are a lot more displaced. I think it’s pretty hard to argue against the fact that there is definitely more of a fracturing in wider society,” she says.

In Sarah Schuman’s Conflict Is Not Abuse, she attributes an increasing reliance communication via email and messaging as a contributor to a loss of intimacy in our lives. And Harold Kushner writes in When All You’ve Ever Wanted Isn’t Enough, “I am afraid that [younger generations] will grow up looking for intimacy without risk, for pleasure without significant emotional investment.”

Image: Michael Prewett

The call-out culture of Bye Felipe and Tinder Nightmares has Thompson conflicted. “On the one hand, whilst shame does play an important role in getting people to reflect on behaviours and whether it’s socially acceptable or not, and whether they should toe the line and behave better, I do think that there’s just a lot of shame being thrown around online. Sometimes it becomes quite divisive and people get more entrenched in their different camps,” she says.

But the accounts are quite useful when it comes to drawing attention to just how pervasive online sexual harassment is. “Women can see, ‘oh it’s not just me that has to put up with this bullshit’,” Thompson explains.

There are endless Instagram accounts dedicated to calling out bad dating manners. While Bye Felipe and Tinder Nightmares focus more on volatile reactions to rejection, twenty-four-year-old Shelby Lorman’s awardsforgoodboys tackles more insidious drains on emotional labour in casual intimate relationships; she finds catharsis in satirical, snarky quips.

To the Huffington Post, she defines these ‘good boys’ as “the ones who wear a feminist badge on their backpack and put ‘ally’ in their Tinder profile but can’t quite understand why it’s a problem that they, as the only dude-identifying person in the room, continually speaks first in their Women’s Studies class.”

On the topic of emotional labour, Thompson says, “that is a huge theme. It is a big thing that’s come out of my interviews, this general sense of real weariness, which can sometimes almost turn into apathy and passiveness.

“[Women are] just constantly trying to figure out how to deflect unwanted advances without provoking a man … [there’s] just an underlying sense of fear at ‘what might happen here’, which I found really, really depressing. There’s just this constant managing of men’s emotions, and I don’t even know if they’re aware of it, but these women – some more than others – really seem to take personal responsibility for them sometimes,” she says.

Lorman hoped that awardsforgoodboys would help let women know that they’re not alone; it asks all people in intimate relationships to hold each other to better standards. “It’s dually horrifying and extremely validating to see how many people have ‘been there’ about so much of my content,” she told Huffington Post.

Image: Viliman Viliman

“I don’t think Bye Felipe and [platforms] like it will change the behaviour of individual men, but I’m not sure that’s the point of it,” explains Thompson. “I think we just need to be having broader conversations around things like consent and I think people just need to learn better frustration tolerance.” She laughs. “I don’t know how you’re going to do that unless you get a whole bunch of these men in therapy.”

Tinder and apps like it can be equally empowering tools. There are apps dedicated for people with STIs (Positive Singles), to lovers of beards (Bristlr). If you live in regional and rural areas, having access to your minority group through a specialist app can allow access to lovers and friends you’d never have met otherwise – and it’s a beautiful thing that gaining access to your minority group is becoming easier. Plus, self-editing can be a boon for people with disabilities that affect confidence around verbal communication.

If you live in regional and rural areas, having access to your minority group through a specialist app can allow access to lovers and friends you’d never have met otherwise.

Coming from a conservative Vietnamese family and suffering from sexual pain disorder vaginismus in her former relationships, in Doing It, Nguyen went as far as to say that online platforms gave her the tools to become the “architect of [her] own pleasure.”

According to Thompson, the presence of more choice – while it might lead to increases in lessening of commitment – has allowed for further experimentation. She says, “People can learn a lot about themselves and what different relationships … can look like by dating widely and more casually – and that’s not a bad thing.”

Published in 2000, bell hooks’ All About Love: New Visions reimagined what it meant to pursue love. The author and activist writes that when women persist in intellectual thought on seeking love, they’re often seen as desperate, needy and deep in overthought. “No one thinks she is rigorously engaged in a philosophical undertaking wherein she is endeavoring to understand the metaphysical meaning of love in everyday life,” asserts hooks. And 18 years since it was published, it seems that to sit and stew on love is often still perceived as undesirable.

While capitalism is often linked with terms like ‘innovation’, the most innovative lessons I’ve been given in love, sex and relationships haven’t come from money-driven start-ups or apps. They’ve come from friendships that have pushed me to do better. They’ve come from visionaries like bell hooks, Audre Lorde, and writers like Sarah Schuman, who re-envision a world where love is transformative: a committed action, rather than a feeling we simply submit to.