Very Important People is our new monthly column in which we seek out notable individuals from all walks of life and find out what makes them tick. This month, Joseph Earp talked to Sam Shpall, a contemporary philosopher who examines the tricky, hard to pin down nature of modern romance.

Is love really the ultimate driving force of all contemporary life? Or is it nothing more than a glorified biological impulse, a desire for procreation obscured by years of artificial myths and lies? And what might happen if your beloved was replaced by a robot programmed to resemble them in every conceivable way? These are some of the questions that we posed to Dr Shpall – read on for his answers.

Close friendships can be just as important as romantic relationships for human flourishing.

The Brag: Why are we so attached to the concept of romantic love?

Sam Shpall: I like your question’s internal witticism, though I’m not sure if you intended it! Romantic love involves an intense form of attachment that produces powerful emotions and, sometimes, revelatory insights. It also involves some unique joys – sex and intimacy with loving partners probably chief among them.

Many have thought that it represents the, ahem, climax of interpersonal relationships, or even, as Erich Fromm said in The Art Of Loving, the mature response to the problem of human existence. I myself am a bit less of a fanboy. Romantic love is wonderful, of course. Yet the obsession with it in contemporary society leads to failures of imagination when it comes to other forms of love.

Close friendships can be just as important as romantic relationships for human flourishing, and would probably be deemed more important than they currently are in a more morally evolved society. Yet how many columns or novels or films or songs explore friendship with genuine sophistication? 1/100th of the number that explore romantic love, I would guess.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

I also suspect that our obsession with a prevailing, yet arguably dated vision of romantic love reflects an unhealthy and unstable channelling of attitudes towards sexuality. It is unsurprising that sex is a central human preoccupation. But I worry that we ask strictly monogamous, lifetime-duration romantic love to do too much when we ask it to satisfy all our sexual desires, as well as our desires for emotional intimacy, intellectual companionship, partnership in life projects, etc.

Is love purely a biological impulse?

Questions about reduction to biology are often misleading. We are biological creatures, so love is a biological phenomenon. But this doesn’t imply very much about the right level of analysis. That depends on the kind of inquiry we’re interested in. Scientific research can give us important insights. For example, it may help us to understand the distinctive nature of early stage romantic love, which may be chemically similar to certain kinds of addictions.

Philosophy is essential, just as science is essential. The tendency of some commentators to pit them against one another is shallow and regrettable.

However, I do not think that this research can alone answer the most significant normative and conceptual questions. It can’t say whether you are required to love your child, or whether it is wrong to love your dog more than you love your grandfather. It can’t articulate the proper place of love in a virtuous person’s life. It can’t tell us how the love of literature or God is related to the love of human beings. Philosophy is essential, just as science is essential. The tendency of some commentators to pit them against one another is shallow and regrettable.

Some of us pride ourselves on being very rational, and yet love is often depicted as the lack of rational thought. Can love therefore be seen as an “escape” from a rational kind of thinking we don’t actually enjoy as much as we think we do?

Nice question. This is a common thought, and a dangerous one. My sense is that it derives from a very Hollywood conceptualisation of romantic love’s beginnings. True, we rarely control what sights and sounds and smells we find most titillating. Plausibly this puts attraction of certain kinds beyond the pale of reason. But attraction is not love.

My (controversial) view is that love is governed by reasons and by standards of normative evaluation, in many of the same ways that (e.g.) belief, intention, desire, and anger are. In other words, love can be irrational, inadvisable, or wrong; and we should not pretend that it is insulated from rationality.

To make this claim is not to suggest, absurdly, that we always actually think and behave rationally in love. There’s no doubt that love can lead to various distortions of our understanding of the world, and to poor reasoning, deliberating, and choosing. We should not embrace this. Appropriately circumscribed, minor irrationalities may have some charm. My concern is that our idealisation of irrationality licenses a lot of imprudent and immoral behaviour. Just think of the “but he’s in love!” excuse…

Is there a reason why we distinguish our love for other ‘creatures’ like humans and pets with our love for ‘things’, like our jobs, or hobbies like movie watching?

In fact, philosophers tend to separate human beings from all other objects of love, including pets. But you’re perhaps right that others draw the lines differently. There are diagnoses of this tendency that I find fairly plausible as explanations, but not as vindications.

One is that we tend to assume that people, or living creatures, are more important than other things. This may be true in general, but I doubt it vindicates a sharp distinction. I think we should pay much more attention to love for activities, artworks, places, and various other inanimate objects. For instance, the love of art is a central ingredient in my own happiness and flourishing. I wish that more people were given the tools to cultivate this form of love from an early age.

Why are we so unnerved by the possibility of our love being replaceable? Could our loved ones be replaced by identical robots, and, if so, should we be freaked out about this?

There are many fascinating issues here. In one sense you could never replace a Mom or a boyfriend with a robot. Even a perfect intrinsic duplicate would not have memories of raising you, or of supporting you when you were in the dumps. (They could have apparent memories, but I take actual memories to involve actual remembrance.)

Likewise, even a perfect intrinsic duplicate would not have the morally relevant property of being the person who raised you, or the person who supported you. (They might think that they were this person, and that consequently you owed them certain allegiances, but they would be mistaken.)

Still, I think we should be pretty freaked out about the possibilities on the horizon. Sex robots are already here, and there’s a lot to say about what that portends. A bigger challenge will be from artificial intelligences that are capable of complex thought and behaviour. Would you choose to date an AI if it is likely to satisfy all your desires better than a human being? Would this be irrational or wrong, and if so why? I’m unsatisfied with my own thinking about these questions. Luckily my students are smarter than I am. I look forward to plagiarising their answers in future interviews.

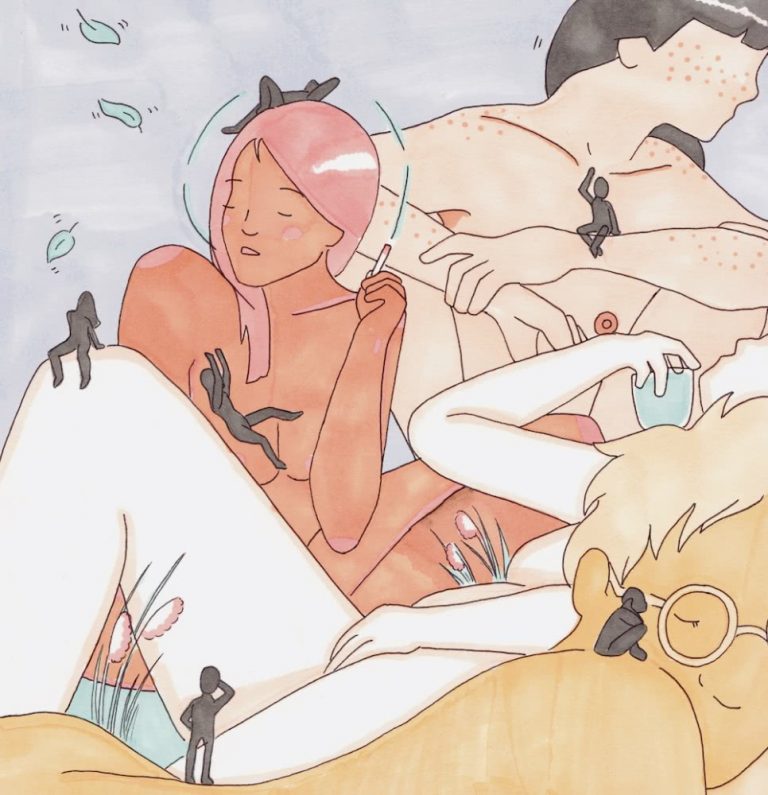

Header image by Jini Maxwell.