Content warning: this article contains discussion of sexual assault

The day I turned 15, my sister gave me a copy of Deja Entendu, the second album by Long Island band Brand New. Up in my bedroom, I listened to it for the first time, and I felt my world shift, somehow, as I heard the thoughts I could never articulate myself from the mouth of a stranger. I went downstairs for dinner a different person.

Six months later, I won a competition to meet the band when they were to come to Sydney with my other favourite band, Blink-182. I wrote a letter to Brand New, specifically its singer, Jesse Lacey, thanking them for everything. Much to my heartbreak the show was cancelled, but I got a signed Deja Entendu poster instead, with “Giselle, I love you” scrawled on it. I had it laminated immediately and stuck it on my bedroom wall.

Over a decade later, in a different city, the poster hung, framed, in my apartment. I had plans to get the astronaut from the album cover tattooed on my forearm. The years had passed, I had changed, but the memories were steadfast.

The day after I turned 29 – two weeks ago – Jesse Lacey was accused of grooming and emotionally abusing minors in the mid-2000s. The girls are the same age as I am now – were the same age as I was then. While I sat in my bedroom and my life changed, so did theirs, but in the worst possible ways.

—

I grew up in the leafy hills of suburban Sydney, where everything looked the same and very little happened. Maybe that’s what drew me to pop punk in the first place – many of the songs were about a yearning to get out of these dreary places. They were full of possibility, and so, I hoped, was my future.

I was an awkward teenager: bespectacled, acne-ridden, mute with terror. All my romances happened online with faceless American boys, who made me feel like maybe there was someone out there who could love me.

When Good Charlotte sang about murdering a girl’s boyfriend to be with her on ‘My Bloody Valentine’, I thought it was hopelessly romantic.

In the years before I discovered feminism — discovered myself — when I thought about the girl I wanted to be, or should strive to be for these boys to love me, my points of references were the songs the boys like them sang.

On Good Charlotte’s 2002 album The Young And The Hopeless, they sang about a “riot girl” who liked the punk bands Minor Threat and Social Distortion, so of course, I sought out music by Minor Threat and Social Distortion. She hated Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, which was code for the boys also looking down on those types of girls – the pretty ones, the prim ones. She was a riot girl, and I wanted to be one too. When Good Charlotte sang about murdering a girl’s boyfriend to be with her on ‘My Bloody Valentine’, I thought it was hopelessly romantic.

The members of Brand New

All my crushes were never returned, or they went for girls that weren’t me, so when The Ataris sang songs like ‘Your Boyfriend Sucks’, where they insisted that the girl didn’t know what was good for her (“you’re better off without him, don’t call him, he’s breaking your heart”) and ‘The Last Song I Will Ever Write About A Girl’, which was much more blatant (“girls are fucking evil”), I wondered why these girls would spurn the sweet, sensitive boys who were giving them the love I craved. How dare they. I hated the girls. I wanted to at once be them, and destroy them.

The men in these bands fought over women like they were property. Brand New and Taking Back Sunday’s infamous feud over a girl resulted in the songs ‘Seventy Times Seven’ and ‘There’s No I In Team’ respectively, without ever once asking the woman in question how she felt. Lacey, a self-confessed “broken-hearted loser”, wished death on his ex-girlfriend for leaving him in ‘Jude Law And A Semester Abroad’ (“even if her plane crashes tonight she’ll find some way to disappoint me, by not burning in the wreckage or drowning at the bottom of the sea”). He sang that he’d do anything she said, and I felt the same way about all these poor boys. I’d never hurt them. I’d be their perfect girl.

The men in these bands fought over women like they were property.

In 2003, music commentator Jessica Hopper wrote of a new phenomenon in the emo/pop punk scene where “every record was seemingly a concept album about a breakup, damning the girl on the other side” – that the music had “become another forum where women were locked out, observing ourselves through the eyes of others”.

The girls in these songs were either put on pedestals or thrown under the bus. They were never rendered as whole or autonomous – just fantasies or bitches who dared to make their own needs and thoughts known. They were the Manic Pixie Dream Girl with heavy eyeliner and studded wristbands.

I was a teenager who had never even been kissed, but desperately wanted to be desired by the boys with guitars and swoopy hair and tattoos; to be good enough for them. The anger and pain of these men’s romantic failures felt like they were made for me, even though they were about girls just like me.

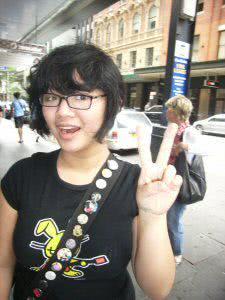

The author, Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen in 2006.

In these examples, the men were not always obviously physically violent, but what they were was more insidious than that. They were entitled – women existed for their consumption and pleasure, as sex robots to be disposed of should they stop working the right way.

For many, pop punk was a gateway to emo, where fantasies of revenge became more graphic: “You know that you are worthless,” Buddy Nielsen sang on Senses Fail’s ‘You’re Cute When You Scream’. “I’ll take you to the top of this building and just push you off, run down the stairs so I can see your face as you hit the street.”

The girls in these songs were either put on pedestals or thrown under the bus.

Few women were visible on stage in this era. When Paramore burst onto the scene in 2005, it was exciting to see Hayley Williams, a girl my age, fronting a band. But even then, she was positioned as being one of the boys – she wasn’t that kind of girl. On their breakout single, ‘Misery Business’, Williams sang with glee about stealing a boyfriend from a girl: “Once a whore, you’re nothing more, I’m sorry that’ll never change.” (In 2015, Williams wrote a Tumblr post admitting that the song had been from a “narrow-minded perspective”.)

In ‘Sk8er Boi’, Avril Lavigne mocked the other girl, the one who did ballet, for becoming a single, stay-at home mum – a life she was damned to for daring to turn down the titular boy. Avril was a cool girl, not one of those girls. We laughed along with her.

Even the women we were meant to look up hated other women. No wonder I did, too.

—

Jesse Lacey is not the first man in this scene, or adjacent ones, to be accused of such crimes against women.

In early 2014, Bright Eyes singer Conor Oberst was accused of rape by a fan, Joanie Faircloth. The allegations were soon after recanted, and a libel lawsuit planned by Oberst dropped – Faircloth claimed that she had invented the whole story. Oberst’s career continued as though nothing had happened.

In my late teen years, I heard that one of my punk idols, Greg Graffin of Bad Religion, had exposed himself to a teenage girl via AIM.

Fall Out Boy bassist Pete Wentz dated a 15-year-old girl when he was in his early twenties: “the best ones are crazy, I guess,” he said of her to Rolling Stone. “There are parts of me that are like, ‘Yeah, we could get married,’ but there are parts of me that couldn’t spend tonight with her.” His was the first penis I ever saw, via shaky Hiptop photos leaked on the LiveJournal gossip community Oh No They Didn’t.

All of these allegations are sickening, but considering the scene that nurtured the perpetrators, they hardly come as a surprise – they are the most monstrous manifestation of the entitlement that was drilled into these men all along.

In my late teen years, I heard that one of my punk idols, Greg Graffin of Bad Religion, had exposed himself to a teenage girl via AIM.

In the weeks since Lacey’s crimes came to light, other women who grew up in the scene have come forward with their own stories of their treatment at shows, or online, at the time. Reflecting on her adolescence in the Long Island scene, Jenn Pelly wrote for Pitchfork: “Bubblegum emo needed its female fans, as evidenced by the swaths of girls who screamed this music back, who took photos, who muscled against stages to get as close as possible without being crushed. But the scene did not really want us.”

And Australian writer Sophie Benjamin wrote in a viral Medium blog post: “These men don’t want grown women. Grown woman see through their bullshit tortured genius messiah act. They want girls — in many cases, literal schoolgirls who are legally unable to give sexual consent.”

At their tamest, the lyrics of these bands were whiny thoughts from the mythical “friend zone” – why won’t she love me? But the horrors that have both physically and emotionally traumatised women in real life find their roots in the way in which these men were permitted – encouraged, even – to think about, and act towards, women in their music.

When you spend so long hearing your idols sing that you’re worthless unless you fuck them, that you’re a piece of shit if you break their heart, you can begin to believe it yourself.

The girls were damned either way.

—

There were priceless things about pop punk – the way everything felt infinite, captured in The Ataris’ ‘In This Diary’ (“being grown up isn’t half as fun as growing up”) and Mest’s ‘Rooftops’ (“up on the rooftop listening to punk rock, nobody believed that this would be our one shot, that was all we had”); the bright-eyed dreams of escape and subsequent realisations of belonging, like The Rocket Summer sang on ‘Brat Pack’ (“I stand back to reflect in this town I hate, and at least just for a second I think I might stay”).

Two of my closest friends to this day met on a Good Charlotte message board in 2003. I met one of them on LiveJournal a year later when we bonded over New Found Glory, and the other outside a Brand New show in 2007. She called me after the show was over and I’d already gone home, and put Jesse Lacey on the phone for me. I squealed for weeks.

When you spend so long hearing your idols sing that you’re worthless unless you fuck them, you can begin to believe it yourself.

So much about this music and this scene made me who I am today, but looking back on it now in my late twenties, I feel for teenage me who resented her femaleness because of these very bands. I was friends with some girls in the scene, but only the ones who weren’t “sluts”, the ones who knew as much about the music as I did. I was a girl who wanted to be one of the boys. I thought that they’d love me if I was what they wanted me to be, so I twisted myself, hoping that the unnatural shape would stick.

I accepted less than I deserved when it came to relationships because my blueprint for love was based on a toxic, entitled male point of view. I devalued myself because I thought I had to. I hated other girls because they were my competition. The unlearning is still ongoing.

We were young girls who didn’t know better. They were older men who did, and didn’t care.

—

It’s a horrible thing to learn that a person who made your teen years destroyed someone else’s. It’s worse still to imagine what it’s like to be one of the women who has to live with that trauma daily – whose hero betrayed them in unforgivable ways.

My relationship with Brand New’s music doesn’t matter anymore. These women’s stories, and lives, do.

‘The Boy Who Blocked His Own Shot’ was a confessional track on Deja Entendu in which Lacey sang about his misgivings to an ex-lover, begging for absolution. The lyrics are hard to stomach now, with the knowledge of what he was doing at the time.

“If it makes you less sad, I’ll take your pictures all down,” he crooned. “Every picture you paint, I will paint myself out.”

Half a lifetime after excitedly putting it on the wall, I took the poster down.