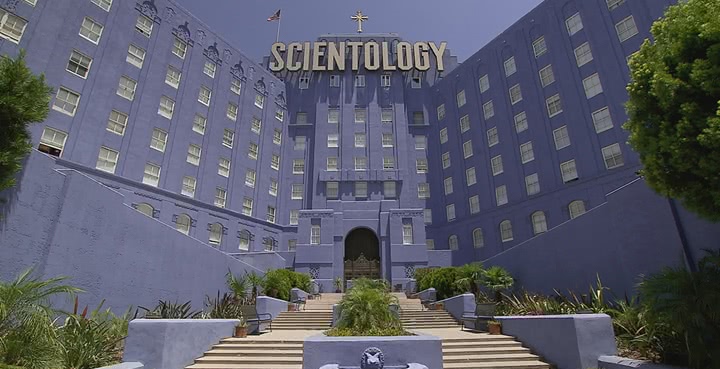

Alex Gibney is excited to feature at this year’s Sydney Film Festival, and with good reason. Not only does he love spending time here in the Antipodes, but three of his films – Going Clear: Scientology And The Prison Of Belief, Mr Dynamite: The Rise Of James Brown and Steve Jobs: The Man In The Machine – are festival highlights. Going Clear has already become the second-most-watched HBO documentary of the last decade, and Gibney’s examination of Brown and the development of soul music is one of the most entertaining accounts you will find of the USA’s turbulent cultural development during the ’60s and ’70s. The Academy Award-winning filmmaker isn’t shy to tackle weighty themes, yet his creative drive remains rooted in the search for a good story.

“I’m compelled by stories, and by character,” Gibney explains. “Sometimes I’m motivated by the injustice that I see around me, though not all the films I do are that angry. But I’m motivated by stories, those ones that come along that you just have to tell because it’s so gripping. There were a lot of years when I was younger that I didn’t get to make very many films, and I feel like if I have the opportunity now, why wouldn’t I do it?

“There are a couple of the more personal ones I’ve wanted to do that I haven’t been able to, but generally speaking when I set my mind to doing one, my record has been pretty good in terms of finishing. There aren’t too many car wrecks by the side of the road. There may be a lot of duct tape and fractured glass by the time I get to the finish line, but I still manage to get there.”

In terms of content, Going Clear, Mr Dynamite and The Man In The Machine would struggle to be more dissimilar, yet there remains a certain tone shared between them. All three attempt to reconcile the nature of truthfulness or factuality when presenting true stories, and how the narrative of each must be more than a simple litany of dates and names lined up in a row. The search for the humanity behind the words, for the story within the history, is what makes a documentary truly memorable.

“It was Werner Herzog who said when you make a documentary you’re not listing facts,” says Gibney. “That would be the phonebook, and the phonebook is a valuable resource but it’s not much fun to read. I think inevitably you’re trying to tell a story. We all love to listen to stories and we’re all fundamentally storytellers; it’s a part of what defines us. So finding a way to do that in a way that’s engaging for people is terribly important.

“I think the documentarian can learn, and indeed has learned a lot from fiction films, and the New Journalism – though it’s now very old – people like Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer, Truman Capote and such, showed that in non-fiction stories you can have an authorial voice and narrative drive that makes it every bit as compelling as fiction, if not more so. Sometimes the events themselves are more unpredictable than they are in any conventional drama.

“Telling a good story is terribly important, and the best non-fiction films shouldn’t be seen as a list of facts. Sometimes I know the critics see it that way. ‘Oh, are there any new facts in this film?’ But it’s the story that is the powerful thing here, the poetry of sound and image that is conveying an essential truth rather than a list of facts. That would be a dreary documentary.”

As such, Gibney’s task as filmmaker is not to archive snapshots of history or compile exhaustive catalogues of character traits, but to bring us into the story – to immerse us, however briefly, in landscapes far different from our everyday. Part of the difficulty, then, is intuiting exactly how that story will take shape. There are countless anecdotes and oddities that may help to add colour or engagement to a documentary, but the risk of distraction from the substance of the story is very real.

“Ultimately it has to do with narrative structure and the themes you decide to focus on. Inevitably you come to a place where there are all these wonderful details and you’d like to include them all, but sooner or later in the cutting room, the gremlins of the story begin to make themselves manifest, and they start warning you not to be distracted by those wonderful details that don’t serve the larger narrative. It was Chekhov who said if there’s a gun on the mantle in the first act, it had better go off in the third, and that kind of condensation of drama is really important, even in documentary. Maybe especially in documentary. As you’re cutting the film down, you’re being rigorous about the kind of tale that you’re telling, and making sure that everything is honing in on itself. Sometimes it’s painful to lose those wonderful details that you’d like to include, but it becomes necessary for the good of the story.

“I think films are all about the road. If you’re not focused on the road you’re on, then you’re never going to find your way. Now I’m really blathering!” he laughs. “I’m getting lost in fucked up metaphors about roads. That’s always a sign of things going terribly wrong.”

Going Clear, Mr Dynamite and The Man In The Machine (dir. Alex Gibney) show at the Sydney Film Festival 2015. For the full program, visit sff.org.au.