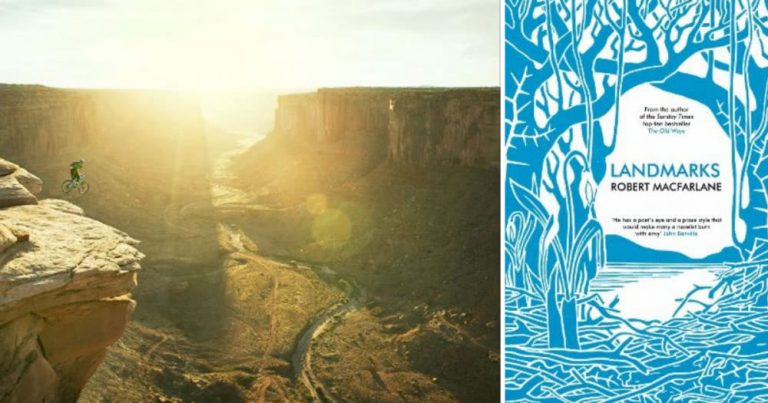

Back in 2015, Robert Macfarlane went viral. A reworked version of the first chapter of his excellent book Landmarks got snagged in the Facebook shares machine, drumming up so much advanced press that upon its eventual release the book hit best-seller lists around the world.

It was a fitting turn of events, really. Not only because Landmarks is bold, lyrical and beautiful, and deserved all the success that was afforded to it – but because of that word, ‘viral’.

Landmarks is itself an examination of the places that language and nature overlap. Part travelogue, part linguistic history, part Ted Hughes-esque paean, the book sees Macfarlane attempt to collate and collect a “word-hoard” of obscure English phrases pertaining to nature. The result is a tome stuffed with shards of language stunning in their precision; words for a host of natural phenomena many of us are losing the need to call by name.

There’s the Shetlandic word af’rug, meaning “the reflex of a wave after it has struck the shore”; zwer from Exmoor, which refers to “an onomatopoeic term for the sound made by a convey of partridges taking flight”; tafolog, a Welsh phrase for any place “abounding in dock leaves”; and kimmeridge, or “the light breeze which blows through your armpit hair when you are stretched out sunbathing”.

In this way, Landmarks is a profoundly textural book; almost linguistically sensual. Macfarlane unearths a host of phrases so sweet upon the tongue that one finds themselves muttering them under their breath once the book is done – words to be repeated, softly, as though rolling a marble around your mouth. Aquabob, a Kentian phrase, translates as “icicle”. Pirr, Shetlandic, means “a light breath of wind, such as will make a cat’s paw on the water.” The ironically beautiful crottle denotes small mounds of rabbit shit.

But there is tragedy to Landmarks too – the kind of quiet melancholy that has been part of the Macfarlane experience since the publication of his first book, the Guardian award-winning Mountains Of The Mind. The loss of the language that describes the natural world is a mirror for the loss of that world itself, Macfarlane argues, writing in Landmarks that “there is no single mountain language but a range of mountain languages; no one coastal language but a fractal of coastal languages; no lone tree language, but a forest of tree languages. To celebrate the lexis of landscape is not nostalgic, but urgent.”

Memorably, at one moment Macfarlane points out the gentle tragedy that has changed the meaning of the word ‘blackberry’ – for many children growing up in a tarmac-clad Britain, it now refers to a device, not a fruit.

Yet one of the great miracles of Macfarlane’s writing is the way that he transforms and elevates tradition. He is no Luddite, and although a book like The Old Ways makes clear its agenda in its title, Macfarlane never aimlessly rages against the modern world. He does not believe in turning back time for the sake of it, and Mountains Of The Mind – his fierce, elegiac account of mankind’s almost ceaseless attempts to conquer mountains – celebrates as many contemporary climbers as it does elder statesmen of the sport.

We have forgotten 10,000 words for our landscapes, but we will make 10,000 more, given time.

Nor is Macfarlane’s work fogged by nostalgia. Although he mourns the injustices levelled against both nature and language, he never pretends that the wild world is some genteel tourist attraction to be picked over and poeticised. His most stirring chapters are those that fully embrace the danger of our world: passages about oceans in “ugly moods”; about the threat of death that hangs heavily over precipice-pocked mountainsides; about foolish men and women stumbling into landscapes they do not yet understand.

And, most importantly of all, Macfarlane has hope – more hope than many. Language might be withering, the natural world might be rolling back, but as far as this author is concerned, there is something within us that will never allow either to die.

“We have forgotten 10,000 words for our landscapes,” he writes in Landmarks, “but we will make 10,000 more, given time.”

Macfarlane hasn’t written a full-length book since Landmarks, but that’s not to say he has kept quiet. After all, this dearth of language he set out to describe is widening like a sinkhole. Aside from his work teaching English to university students, the 40-year-old Nottinghamshire-born writer has authored a work on the joys of reading, penned liner notes for the band Grasscut and even jumped art forms: the next major Macfarlane work will be released not as a book, but as a film.

Mountain, a collaboration between Macfarlane, director Jennifer Peedom (the mastermind behind Sherpa, an affecting look at the lives of those who lead tourists up the side of Everest), actor Willem Dafoe and cinematographer Renan Ozturk will make its debut here for Sydney Film Festival.

Little is yet known about the work – it has been vaguely described as “a suitably uplifting, symphonic ode to high places”. But in any case, it certainly seems like a continuation for Macfarlane; the next instalment of a songline he has been following now for years.

As the man himself put it in an interview with The Independent: “I seem to have spent 15 years coming down from the mountains.”

Mountain is showing as part of Sydney Film Festival 2017 at the State Theatre on Saturday June 17 and Hayden Orpheum Cremorne on Sunday June 18. The ACO will perform live with a special screening of the film on Monday June 12 at the Sydney Opera House.