“A whale has eaten one of the trainers,” a 911-caller is heard saying at the start of Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s documentary Blackfish. The call was made from SeaWorld Florida in 2010, when trainer Dawn Brancheau died in the jaws of the largest orca in captivity, Tilikum. Brancheau was “scalped”, her arm devoured, and through interviews and archival footage, Cowperthwaite traces this gruesome incident to its roots, exposing the brutality of the captive orca industry.

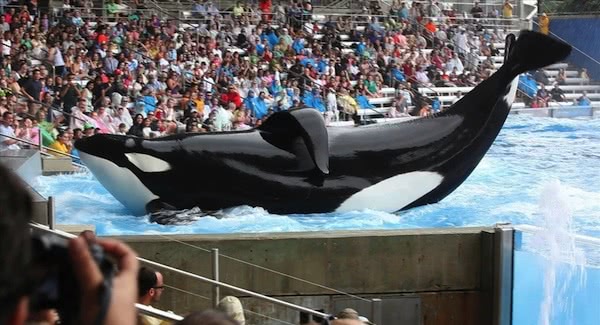

Whatever ethical justification SeaWorld might claim in keeping orcas for ‘educational’ purposes is obliterated by this film. And that’s the film’s agenda. Among the damning revelations, one trainer describes the juvenile Tilikum as being very cooperative — adding that if orcas don’t perform tricks correctly, they’re starved until they do. This sits uncomfortably with the sentimentalism of SeaWorld shows, which exalt some mythical connection between humans and orcas.

Just as there’s no real bond between the whales and their human jailkeepers, we learn the whales have no bond between each other. They’re collected from foreign oceans and traded between sea-parks according to commercial considerations, with no attempt to group individuals that communicate using the same ‘dialect’, or to keep families together. In heartbreaking footage, the orca Kasatka is shown making screeching vocalisations after her calf was removed to another park — vocalisations identified by audio scientists as being long-range calls, intended to locate the lost calf. Between this scene and the tearful testimony of the grizzled fisherman who originally helped capture the infant Tilikum, I was about ready to walk out because I didn’t want to learn any more.

The skeptical postgrad in me wanted to pick apart this film’s obvious bias; however, it doesn’t take much imagination to divine that these wild animals’ lives are being royally screwed by an unethical corporate machine. Free Willy!

3/5 stars

BY SHIRIN BORTHWICK

Blackfish is in cinemas now.