In 1998, the band Le Tigre, fronted by once and forever riot grrrl Kathleen Hanna, released ‘What’s Yr Take on Cassavetes’, which answers its titular question with alternating cries of “Genius!” and “Misogynist!” These responses are cheeky extremes, but they speak to a real struggle many viewers have when watching the work of American filmmaker John Cassavetes.

The progenitor of the American independent film scene, Cassavetes’ films are confronting character studies of tormented people trying (often through screaming matches) and failing to understand themselves and each other. And as much as I love many of the director’s films, it’s hard not to hear Le Tigre rattling around in my head as I watch them, struggling to place my knee-jerk repulsion at some of his ideas.

In the films of Cassavetes, men are inherently violent (mostly emotionally, though sometimes physically), primitive creatures who take out their inner frustrations on those around them. In A Woman Under the Influence, Cassavetes’ most famous film, a husband’s inability to understand his wife’s erratic behaviour causes him to mostly communicate in yells and – in one uncomfortable moment – a hard slap. He doesn’t change by the end of the film.

In Husbands, maybe the go-to film for evidence of Cassavetes’ misogyny, three middle-aged men freak out when a childhood friend dies, and they go on an extended bender where they treat everyone – especially the women around them – with a mixture of callousness, violence, and immature spite. They are unable to untangle themselves, and so they take it out on everyone around them.

That kind of behavioural description can be applied to the men in almost every Cassavetes film, and I can’t think of a single one where these male creatures grow as humans. Cassavetes seems to think that ugliness and misogyny are intrinsic to the male gender. Not quite a “boys will be boys” attitude: more of a dejected acceptance of the evils of men.

I don’t think that Cassavetes was a misogynist. His films are all absolutely critical of this abhorrent behaviour. But he is a romantic filmmaker, in the sense that he clearly values the nobility of his men’s futile attempts to change. At their core, Cassavetes’ films deeply respect every character as deeply human and worthy of compassion.

That’s a fine idea, but it inspires a bit of queasiness when one considers that many of these characters are – in Cassavetes’ world – irreparably awful men.

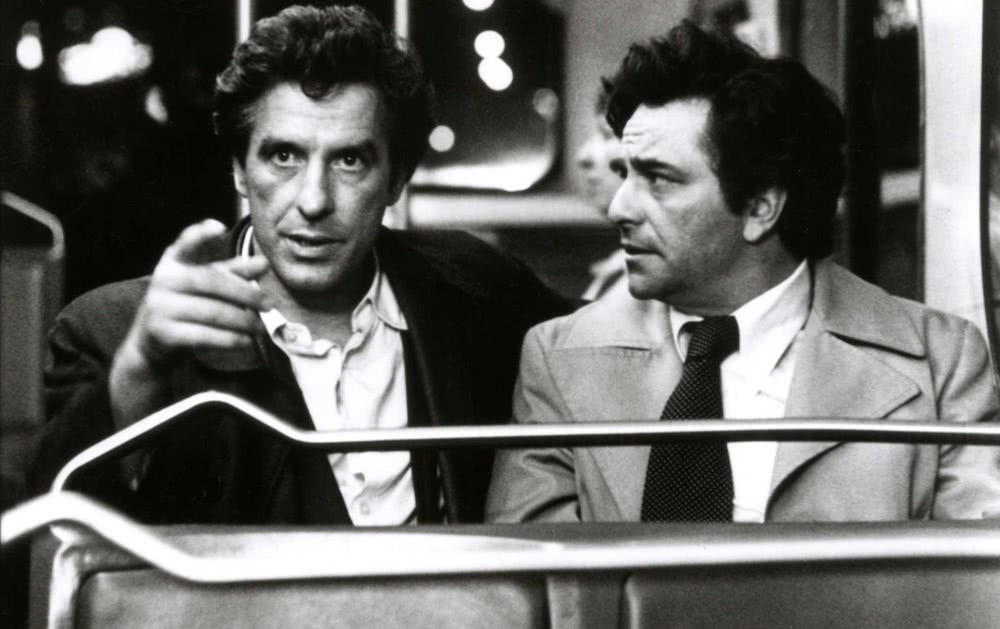

One of the best films that deconstructs this worldview is Elaine May’s – soon to be released as part of the Criterion collection – 1976 Mikey and Nicky. May’s film depicts the very long night that follows after Nicky (Cassavetes himself), a low-level mobster on the run from a contract on his head, calls his childhood best friend Mikey (Peter Falk – a long way off from the grandpa in The Princess Bride) for help. Mikey is as bitter as Nicky is paranoid, and their erratic, panicked odyssey across the city releases years of pent-up frustration and rage.

Elaine May was remaking a Cassavetes film in her own image.

May, who came to prominence working with fellow comedian Mike Nichols (who later made The Graduate) before directing the cringe-comedy classics A New Leaf and The Heartbreak Kid, uses the long takes and cluttered mise-en-scene of her previous work and pushes them to almost parodic extremes, resulting in an exhausting cinematic experience that perfectly emulates the feeling of Cassavetes’ directorial works – if not quite the look (Cassavetes would have used more close-ups).

The “one long night” conceit pushes the typical Cassavetes behaviour to its frantic end-point: any charm built into this type of characterisation is shaved away by the sheer relentlessness.

In essence, May was remaking a Cassavetes film in her own image. Her cringe-comedy background lends itself well to this sort of sweaty drama, but she’s seemingly less interested in how these men want to change and more in what devils they already are.

They are petty, they are selfish, and they barely even like the people they’re supposed to love. There is no nobility in their heart of hearts, no honour among thieves – they’re just two low-level arseholes looking out for number one, even and especially if that means screwing over each other, their wives, and the women around them.

In a key scene in the middle of the movie, Nicky and Mikey (both married) go to the house of the former’s mistress, Nellie. Promised a little action of his own, Mikey uncomfortably sits on a garbage can in the kitchen while Nicky has sex in the living room. After Nicky pulls up his zipper, Mikey kisses Nellie, under the mistaken impression that she is expecting him.

When she fails to reciprocate, Mikey slaps her, and Nicky berates her for her lack of hospitality. Nothing quite so extreme ever happens in any of Cassavetes’ films, but Mikey and Nicky’s flippant attitude towards their misogyny is eerily reflective of how his characters tend to act. Cassavetes never wrote a scene so unambiguously horrific but May saw a clarity of ugliness in his films – and was bold enough to put it onscreen.