There’s a moment in Jem Cohen’s Instrument – a documentary about the seminal Washington D.C. punk band Fugazi – where drummer Brendan Canty explains that his sister’s boyfriend believes the band live together in a group house without any heat. It’s a weird rumour that doesn’t seem to surprise guitarist and co-frontman Ian MacKaye: “The problem is if you don’t say anything, then people place your thing on you. They say who you are.

“But then if you try to steer it all,” MacKaye continues, “It’s premeditated … You’re manipulating it.”

So how do you solve a problem like this? How do you create an honest portrait of a band that dispels misconceptions without creating a narrative that isn’t genuine? With music documentaries, there’s always a degree of artificiality. Candid behind the scenes moments are edited together to form some kind of narrative, and there’s usually an awareness on the subject’s behalf that leads to them performing for the camera.

Instrument answers a few questions you might’ve had about the band, but still remains vague enough to let you to make up your own mind about who Fugazi are.

Through a collection of material consisting of live concerts, interviews, studio recording sessions and behind the scenes tour footage – amassed from 1987 to 1998 – Instrument answers a few questions you might’ve had about the band (no, they don’t live in a freezing share house subsisting on a steady diet of rice), but still remains vague enough to let you to make up your own mind about who Fugazi are. The band isn’t so much steering their image as they are giving the driver advice on which route to take.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p6DnzPyDkM0

What Instrument does better than anything else is capture Fugazi’s sound through the assembled visuals, constantly jackknifing and throwing the audience off-balance. The band will be locked into a hypnotic rhythm, MacKaye and co-frontman Guy Picciotto dawdling around the stage before an abrupt explosion of energy. MacKaye and Picciotto’s bodies will contort and convulse for seconds, their guitars screeching, before they will suddenly return to their subdued demeanor and sound, almost as though the last few seconds hadn’t happened at all.

Love Film & TV?

Get your daily dose of everything happening in music, film and TV in Australia and abroad.

According to Picciotto the band doesn’t pre-plan their setlists, so every live show is a unique improvisation. That uncertainty translates into the film’s editing: just as a song peaks it’ll cut to the band eating in a food court to a close up of MacKaye’s face as he screams vocals into the microphone, then to bassist Joe Lally attempting to bathe in a motel shower that barely comes up to his chest. Watching Instrument for the first time, you don’t know what you’re going to get.

Instrument both looks and feels like no other music documentary.

From day one Fugazi have always done everything on their own terms. Forming in 1986 and going on an indefinite hiatus in 2003, they existed in a period when the underground transitioned into the mainstream, with every major label snapping up whatever alt-rock band they could in the hopes of scoring the next angry-guitar fuelled platinum hit. Fugazi refused to march to the drum of these major labels – MacKaye: “I have a lot of contempt for the record industry” – and it worked. They remained independent throughout their career and still managed to out-sell and out draw the bands on those big labels. They’re the poster children of do-it-yourself punk ethics for a reason, unwavering in their integrity and maintaining the respect that comes from not selling out, the cardinal sin of punk rock.

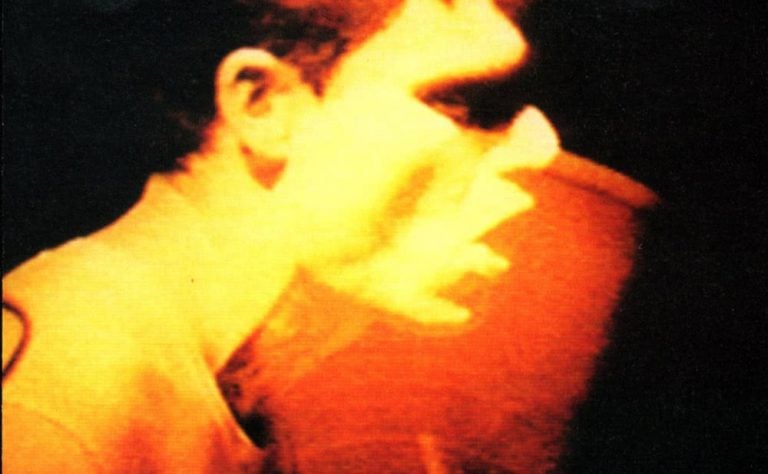

Instrument both looks and feels like no other music documentary. The film opens with an ethereal live performance, filmed on Super 8 stock that’s been slightly slowed; it’s poorly lit and colour-graded a sickly yellow. The band’s bodies blur and smear as they perform (Cohen would use stills from this scene for the film’s poster and the soundtrack’s cover art). The end result of Cohen’s collection of disparate snatches of footage is something raw and experimental – crude film stock and unedited video footage combined in a way that feels honest, never distorting who Fugazi are. While you might get the odd shot that flirts with the realm of art-school pretentiousness, the context renders that pretension moot. Picciotto’s erratic dance moves and almost liquid body are the perfect focus for Cohen’s lens.

If you’ve listened to Fugazi but never really looked into the people behind the music, Instrument is an indispensable document of one of music’s hardest working acts, and one of the most important bands of the ’90s. In their review of the band’s third album, In On The Kill Taker, Rolling Stone called Fugazi “the only band that matters.” An exaggeration, sure, but after watching Instrument, it’s hard to argue otherwise.

Instrument screens at the Sydney Opera House featuring a Q&A with Guy Picciotto on Friday, May 25 and Saturday, May 26.