If there was one thing that could have killed Jay-Z’s career, it was success. The music of Shawn Carter has always been defined by its scrappiness, his songs underpinned by an explicit sympathy for the outsider and the underdog.

Reasonable Doubt, his 1996 debut record, might have featured work from producers such as DJ Premier, a superstar in his own right, and a guest spot from The Notorious B. I. G., but the thing was emphatically, almost spiritually DIY in its outlook.

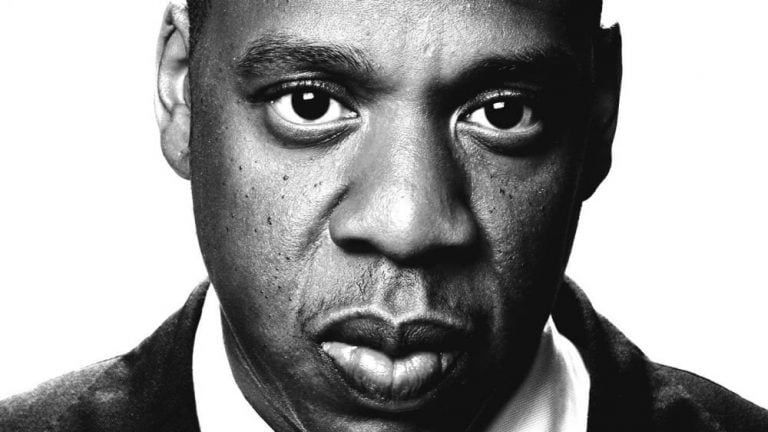

Peppered with stories plucked from Carter’s time as a drug dealer and bolstered by thumping single ‘Dead Presidents II’, Reasonable Doubt was a spittle-soaked Mafioso oddity, a story of redemption and revolution. Sure, it might have been dusted with a fine layer of the braggadocio stylings of the time, and the front cover – a black-and-white photo of Carter with his head bowed, cigar shoved between fingers – might have seemed like an image of opulence, but this was no shimmering slice of capitalism, and Carter’s story was not yet one of success.

Reasonable Doubt was also explicitly political – albeit in a deliciously undisciplined sort of way. Carter spent little time on bars about the ins and outs of the American political machine, but he did observe the devastation of its worst policies. “I’m out for presidents to represent me,” whip Nas’ words across the ‘Dead Presidents’ hook, and the song, like the album, is no carefully worded political speech – it is a howl, a desperate, ragged request for change.

Jay-Z could never write a record like Reasonable Doubt again. The musician Carter used to be is gone – he evaporated just after the album’s release, somewhere around the moment the record began charting on the US Billboard 200.

Reasonable Doubt was of a different time in the man’s life; miraculous not only because of its beats, and the jagged glass bottles of its choruses, but because someone facing Carter’s adversaries had managed to avoid buckling. It was, in its own right, a great hulking example of the human capacity for survival.

And it made Jay-Z rich. It has never really stopped making him rich either: by 2006, it had sold 1.5 million copies in the United States. Suddenly, through the sheer force of his will, Jay-Z had become a viable commercial prospect – a multi-faceted, endlessly creative artist with all the heft of a pop star.

Which could have killed him. It could have killed everything that made Reasonable Doubt special; could have killed the drive in his work; the raspy, sore edge to his distinctive voice.

A lifetime apart: In My Lifetime, Vol. 1

Instead, it changed him. By the 1997 release of In My Lifetime, Vol. 1, Jay-Z’s alteration was complete. You only need to turn to the second record’s cover to see that – though another black-and-white photo, this one emphasised Carter’s handsome face; the understated yet enviable gold watch sitting plump on his wrist.

Jay-Z was no longer the dangerous, bloodletting Robin Hood type he had been on Reasonable Doubt – but he had not allowed himself to be tamed either.

https://vimeo.com/209645272

That subtle change was represented in the sound of the record, too. Rather than the excess that had defined Reasonable Doubt, In My Lifetime was an album of polished surfaces, gripped within a reflective sheen. The singles were more obviously singles – more clipped, tightened, easier to play on the radio. And rather than a vicious mastermind like B.I.G., Jay-Z recruited the likes of Blackstreet, Foxy Brown and Lil’ Kim, pumping his album with R&B-indebted crooners.

But despite all that was different about Jay-Z’s new direction, In My Lifetime was not an abandonment of his philosophies. Money might have redefined his world, but it had not altered his sensibilities or his sympathies. There was still the anti-authoritarian streak in him, expressed most notably on ‘The City Is Mine’, a paean to his departed friend B.I.G. “I’m takin this rap shit serious, to my demise,” he spat. “I let the world know that the city is mine.”

Watching the throne: a benevolent leader

Of course, Jay-Z knew that by embracing such alteration, he left himself open to be branded as a hypocrite. He was a bona fide superstar, and before too long he’d be a businessman to boot – soon he’d have the wealth, power and privilege that so often has the ability to insulate one from the drudgery and mundanity that we generally mean when we talk about ‘real life’.

What could Carter understand about the struggles that afflicted those listening to his music, now he was famous? How could he sing about the streets any more, when his was so obviously paved with gold?

But rather than duck away from these inconsistencies, Jay-Z embraced them. They became his defining characteristic: he evolved into the concerned millionaire; the renegade businessman; the anarchic venture capitalist. He might have stopped being a Tony Montana type, but by In My Lifetime he had become a gangster of a different sorts: a wolf of Wall Street, manipulating the system from the outside rather than banging against its doors.

By making that change, he saved himself from obsolescence – but he did more than that too. In his evolution, Jay-Z became the defining American musician of the late ’90s and early 2000s. In so many ways, the man he became on In My Lifetime is a kind of prototypical American male – a more socially conscious Donald Trump; a more renegade Steve Jobs; a fire-spitting Barack Obama.

The story of Jay-Z is the story of late capitalism, both its booms and its busts. It’s the story of a man who profits off a system he despises – a system actively rooting for his destruction – and then, when he has enough, wants more.

Jay-Z’s new album 4:44 is out Friday June 30 through Tidal.