A couple of years ago, I worked as a teacher’s aide at a primary school in Bondi. I loved the school, and the kids – except on windy, rainy days. Then, stirred up by the weather, even the most pleasant and respectful of children would turn into mutant, wild-haired brats. You’d walk into the hall at lunchtime and there’d be blood on the walls. Staff would stumble out when their shift was done bleary-eyed and blinking, looking like Tom Hanks at the beginning of Saving Private Ryan.

That is, until someone hit upon the bright idea of putting on Abbey Road. We’d tried music before, of course, but with limited success – not even the usually awesome power of The Wiggles was enough to calm the horde. But Abbey Road was different. You’d put it on, and the kids would dance and skip around the hall for 30 uninterrupted minutes – and then, pleasantly depleted, they’d sit propped up against the walls and listen to ‘Golden Slumbers’, smiles across their faces.

The very first day we tried the Abbey Road therapy, the principal, confused that the customary bloodcurdling screams were not emerging from the hall, ducked her head around the doorway. She looked stunned. “Paul McCartney can do anything, I guess,” she said, eventually.

There were intimate moments for the people who love intimate moments, McCartney playing ‘Blackbird’ onstage by himself

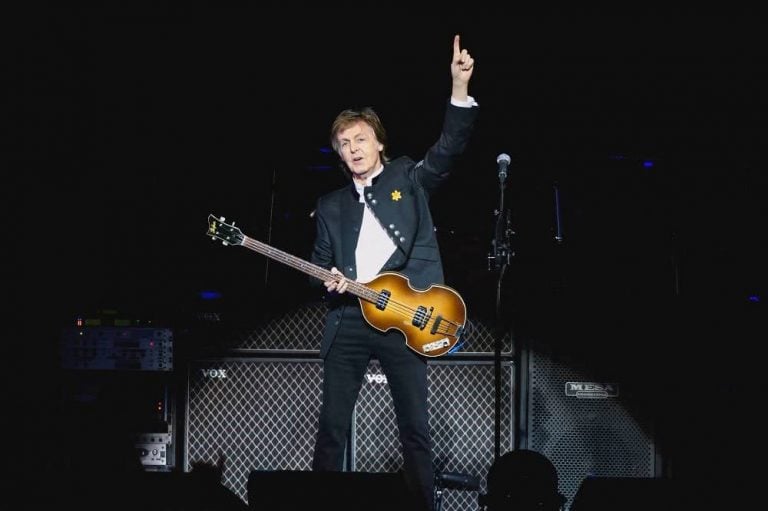

He can. I have been convinced of that since my parents bought me a CD copy of Let It Be when I was eight years old, and I am only more convinced of it following McCartney’s Sydney show at the Qudos Bank Arena. Not that it can even be described as a show, really. It wasn’t a gig as much as it was a three-hour-long, 40-song-strong celebration of a life; part Broadway musical, part confessional.

He played the hits, because of course he did – because what would a Paul McCartney show have been without ‘Hey Jude’ and ‘Let It Be’? But none of these songs seemed performed out of some sense of obligation. Never once did McCartney appear to resent ‘Eleanor Rigby’ or ‘Love Me Do’, and though he quipped about the visible difference in the audience’s enthusiasm when he played songs off his underrated record New versus when he played a Beatles classic – “When we play a Beatles song, the place lights up with your phones, and when we play a new song, it’s like a black hole” – he seemed ultimately unperturbed.

That kind of kindness was to be expected – after all, it’s just a natural biproduct of McCartney’s supreme empathy. Paul McCartney understands not just his audience, but people. He knows what people like – what they want. And not in the way a used car salesman understands people, but in the way parents understand their children; the way lovers do.

McCartney didn’t need to make a big deal about including ‘Give Peace A Chance’, tacked on as a coda to an incredible version of ‘A Day In The Life’. The song did the talking for him.

There were bells and whistles thrown in for the people who love bells and whistles: the climactic pivot point of ‘Live And Let Die’ was accompanied by a small chorus of fireworks, flameballs and explosions, and the opening strains of ‘Mull Of Kintyre’ beckoned a full marching band onto the stage. And there were intimate moments for the people who love intimate moments, McCartney playing ‘Blackbird’ onstage by himself, a riser floating him up into the rafters of the arena.

There was history to be covered. McCartney told stories about run-ins with the Stones and Jimi Hendrix; dedicated a song to John and a song to George; played the very first song he recorded with his proto-Beatles band, The Quarrymen. And there was a present to be alluded to, however subtly: McCartney didn’t need to make a big deal about including ‘Give Peace A Chance’, tacked on as a coda to an incredible version of ‘A Day In The Life’. The song did the talking for him.

Towards the end of his life, the comedian Andy Kaufman played a series of Christmas variety shows. Audiences were treated to milk and cookies beforehand. A man dressed up as Santa distributed gifts amongst them. Kaufman ran through the crowd, high-fiving everyone whose hand he could reach. All of the things we think of as kitsch, and sentimental were leaned into; embraced. And audiences melted like so much butter.

That’s what McCartney’s show was like. And that’s what Paul McCartney can do: he can come into your life, simply, asking nothing of you, and change everything.

For a full library of snaps from the Paul McCartney Sydney show, head here.