Set in the blistering outback outside 1920s-era Alice Springs, Sweet Country is one of the most potent Australian films of the decade. The second feature by celebrated director Warwick Thornton, the film has already swept through the Venice and Toronto international festivals to great acclaim, picking up the Premio Biasto d’Oro award at the former.

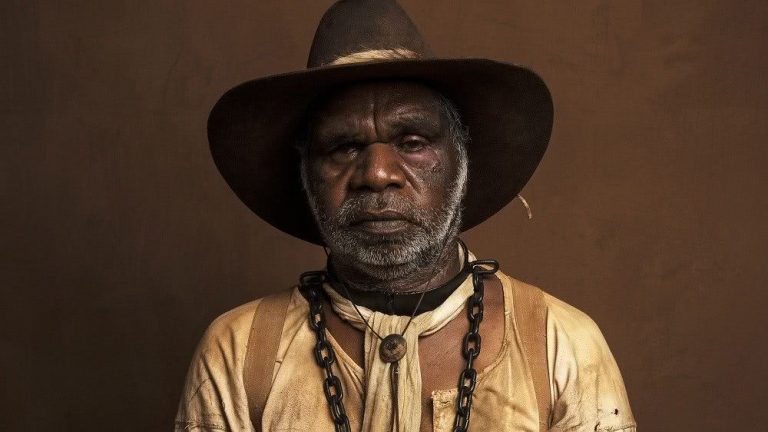

It tells the story of Sam Kelly, played by Hamilton Morris, who makes his big screen debut. Kelly and his wife work unpaid on the property of Fred Smith (Sam Neill), and while Smith is a comparatively benevolent man of God, the Indigenous people of the region work for him as slaves.

The film opens as Sam and his wife are briefly “loaned” to a belligerent newcomer, a World War One veteran called March who treats them with contempt. When an Indigenous boy flees his property, March pursues the escapee onto Smith’s land and opens fire on Sam and his wife, before being killed by Sam in self defence. Sweet Country then becomes a chase movie of sorts, as Sam flees across the breathtaking and brutal outback planes, pursued by the police.

Just as the conditions prove punishing for the characters, the cast also found themselves at the mercy of the Red Centre, with Neill recalling that locations were “beautiful in the morning, beautiful in the evening, and pretty shithouse around midday.”

By a week in I was like, ‘Oh I don’t give a shit, I’ll do whatever the bloody hell I want.

As a result, Thornton was conscious of the strain placed on the film’s cast and crew. “In the heat of the day we didn’t have the luxury of a three hour nap. We just had to keep working, because of the lower budget and requirements of time,” Thornton explains.

During filming actor Bryan Brown, who plays the relentless Sergeant Fletcher, was bitten by a spider and had to be hospitalised. In spite of such setbacks, Brown maintains the set was pretty easygoing. “Otherwise it was a snack,” he says.

And in any case, Brown believes any difficulties were far outweighed by the benefits of the location. “When you’re doing these sort of movies and you’re in Alice Springs, or any other place out in the middle of the country, you get in the car in the morning to drive to the set and you’re sort of loving being there. You’re not driving through the traffic in Sydney.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Neill. “There are mornings where you think, ‘Oh my god, this is just incredibly beautiful’ with the light coming up. Or a storm would come in, and you’d see a rainbow and just roaring mud and rain.”

Both Neill and Brown play characters who are morally layered, and completely at odds with the natural environment. “I thought my character was playable,” Brown says of the sergeant. “I didn’t read it and think, ‘Who’s this and what’s he doing?’” Nonetheless, when pressed on the question of playing a complicated soul, he admits his approach erred significantly towards pragmatism.

“You play the scenes as truthfully as you can and the complexities will come, as it’s all added up in how people view that character.”

Neill agrees. “The trick is not to judge your own character, otherwise you’re doing a sort of judgemental performance. You’ve got to inhabit that character. A year later you can look back and think he’s a man of compassion and belief, but also foolish. There’s nothing duller than a two-dimensional character.”

Sweet Country is also the first release directed by Thornton that he hasn’t written. “Right at the beginning I was kind of like, ‘The writer is all knowing, all good’,” Thornton explains of his process. “If it was written that it was a red tea cup, I’d say, ‘It has to be a red tea cup’. And then by a week in I was like, ‘Oh I don’t give a shit, I’ll do whatever the bloody hell I want.’”

Indeed, it was by abandoning the strictly adherent approach that he credits with allowing him to “spend more energy as a director making a better film from an amazing script. Every point of making a movie is about raising the bar. When they write the script that’s the first level. And when you shoot the script, that script needs to become images better than the script. And then when you edit the film, those images need to turn into something better than what you shot.”

Another significant directorial decision was to cast first-time actors for all the Indigenous characters from the Alice region in an effort to reinforce their connection to country. “This story was their families’ story,” says Thornton. “Their grandparents worked for free all their lives and that was the only way they could actually stay on country and be connected to the land and to the spirits that they believed in.”

It’s similarly personal to Thornton. “I’m Kaytej, a tribe from about 200 kilometres north of Alice Springs, and my mother was born under a tree … to a white pastoralist and an Aboriginal woman. And my grandmother worked for free, so it is my story.”

And with that personal connection came responsibility for authenticity – not to mention a “responsibility to not get too angry. It’s a time and a place, and you need to balance all of that sort of stuff and a responsibility to actually make intelligent cinema. You’ve got to balance all the characters, and give people reasons for being; reasons to make those choices.”

Sweet Country is in Australian cinemas now. For other film reviews, read our thoughts on The BBQ, here.