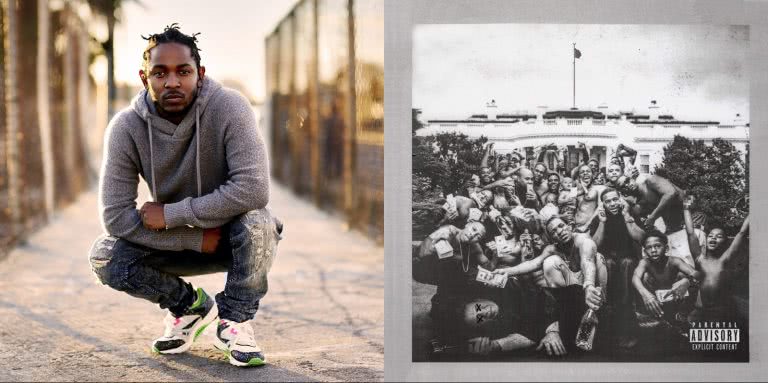

Like the pop of a Glock or the hand of God descending, Kendrick Lamar’s third studio albumTo Pimp A Butterfly came out of nowhere this time last year, immediately silencing both its critics and its fans.

It was too big to initially comprehend, at once divine and yet utterly free of pretence. Now, almost 12 months after it dropped and ahead of Lamar’s upcoming visit to Australia, we take a closer look atthis modern classicin an attempt to discover what makes it work.

–

Kendrick And Home: Why Compton Is Embraced And Rejected

In 2005, facing a 45 per cent spike in the murder rate, the LA Sheriff’s Department began its annual“gifts for guns” program in Compton, LA. The program incentivised the populace to turn in their firearms, offering all those who surrendered their weapons food vouchers worth up to $100.

Such a story offers a welcome insight into the twin troubles affecting Compton: its people are both hungry and armed.

Compton haunts Lamar like a curse and guides him like a star. In a strikingly honest interview with Rob Markman last year, he explained how the city affected him. “I’ve only been in this industry for three or four years,” he says. “I can’t forget 20 years in the city of Compton.”

Compton can be felt all over To Pimp A Butterfly–its streets criss-cross the album like veins. In many ways, the record is born of conflict and obsessed with it, concerned with the plight of a good person in an inherently bad world. It’s consumed by Lamar’s desire to embrace his background, even as he knows that the act of rejecting its gang culture may well have saved him from life in jail.

Such a contrast informs the album’s melodic content. It explains the record’s mix of styles; why the work smashes up jazz and hip hop strains, forcing the genres into striking collusion. By combining silvery licks of the flute with verses about wiping your ass on ‘Institutionalized’, Lamar elevates the streets to the level of the mythic and lowers the mythic to the level of the streets. After all, jazz has largely been accepted by the predominantly Caucasian critical establishment, while hip hop remains ignored by some, dismissed as juvenile or underdeveloped. By fusing these two musical traditions together, Lamar straddles two seperate worlds, revealing their shared concerns and linked desires.

But the clash between the low and the high brow can be felt most strongly on ‘King Kunta’, a diss track with a difference: it is an open celebration of hip hop’s braggadocio culture (hence lines about running for Mayor of Compton, and a damnation of his ghost-writer-utilising competition) that also throws historical and literary references into the mix.

‘King Kunta’is a song about being a slave to both destiny and Caucasian American society, but being a king of your own potential; a song about being both confined by African-American culture and freed by it; a song about being mad, but not stressed. It is a song that pays homage to Lamar’s spiritual and physical home – Compton, the birthplace of N.W.A,the group that directed the young rapper as much as any other– while also distancing him from it, adding layers of historical perspective other rappers would baulk at.

It’s both a love letter to home and a damning rejection of home’s very existence.

–

Kendrick And Hate: Rage Against The World And Rage Against The Self

To Pimp A Butterfly is a kaleidoscope; a blinding collection of images, scenes and stories. But one of the most striking moments of the record is also its most simple and primal. It’s the vision contained within ‘u’ –a shot of Lamar in a hotel room, alone and lonely, torn apart from within.

It’s not so much a shred of self-portraiture as it is an incident of self-flagellation. Indeed, Lamar saves the majority of TPAB’s vitriol for himself. He considers suicide on ‘u’, accidentally ignores God on ‘How Much A Dollar Cost’, and weathers a barrage of assaults on ‘For Free?’ from a seething African-American ‘mammy’ –a racially charged cliché that Lamar artfully deploys to further denigrate himself, playing up to the image of the “proud monkey” he will later draw from his extensive grab-bag of Caucasian-created slurs.

But in typical Lamar fashion, these shocking moments of self-hatred are not wholly personal, nor insular in nature. Lamar’s distressed emotional state is representative of the distressed state of his culture; of his world. Self-loathing amounts to the loathing of his people, and the problems that afflict them. Indeed, the internalised violence on a track like ‘u’ is echoed again on a broader scale on ‘The Blacker The Berry’, a song that condemns gang violence as a kind of hypocrisy, a short-sighted failure that allows Caucasian oppressors to continue their fascist work.

The suicidal thoughts of ‘u’ are the same suicidal actions of ‘The Blacker The Berry’, and the division of the mind is inherently linked to the division of culture. The bottom line is this: Lamar knows that earthly pains are spiritual pains; that the struggles of the individual are the struggles of the community.

And so he tears himself apart. Reduces his talents. And sets himself ablaze.

–

Kendrick And Heroes: Borrowing From Influences And Becoming His Own Man

Yet from the ashes of destruction, Lamar arises. TPAB may contain instances of terrible self-directed violence, but it moves above all that hatred, transforming the horror into grace. The clinking bottles that get glugged away by Lamar’s alcoholic consciousness on ‘u’ become clinking cowbells towards the start of ‘Momma’, an auditory echo that represents the transition from destruction to construction.

Though the figure of Lucy, the Devil herself, tempts Lamar throughout the piece, ultimately he is carried to redemption by three heroic figures.

The first is God, played by James Fauntleroyof The Underdogs on ‘How Much A Dollar Cost’. It’s no coincidence that Lamar’s stand-in for the almighty is both African-American and a rapper; for Lamar, hip hop itself is a religion, a guiding force that forever prompts him to do good. It is a vaguer, auditory version of the protector who has his back in the relentlessly optimistic intro to‘Alright’.

Indeed, the second icon that carries Lamar over the threshold of paradise is another musical figure: Tupac, Lamar’s idol. It is to Tupac that Lamar turns for guidance on ‘Mortal Man’, splicing himself into an interview with his hero, and indeed the poem that crops up throughout TPAB– the single thread that binds the whole thing together – is revealed to be a proclamation levelled at the departed rapper.

Lamar turns to Tupac, begging him for direction. But in the album’sfinal three lines, Tupac disappears. In Lamar’s moment of truth, his hero falls silent. “What’s your perspective on that?” Lamar begs. “Pac? Pac? Pac?!”

It’s a moment of abandonment, but one of strength, of realisation, of self-reliance.

That’s why there’s only one choice that faces the listener when they are done listening to Lamar’s final, desperatewords.ToPimp A Butterflyis not a dead end, it’s a loop. It’s up to the listener to return the needle back to its starting point.

When one does this, Lamar’s “Pac?!” is met with silence, but only a few bars of it. From the emptiness rises the powerful opening of‘Wesley’s Theory’,the album’sincendiary opening track. Lamar answers his own question: he is his own third saviour. By crying out for direction, the rapper has created his own new route; by simultaneously rejecting and accepting birthplace, he has created a new home both traditional and temporary. By tearing himself to pieces, he has built himself up.

And through the process of searching for his hero, Kendrick Lamar has become his own.

To Pimp A Butterflyis out now through Aftermath/Interscope. Lamar will play a headline Sydney show on Wednesday March 23 at Allphones Arena. He’s also appearing at Bluesfest 2016, Thursday March 24 –Monday March 28.