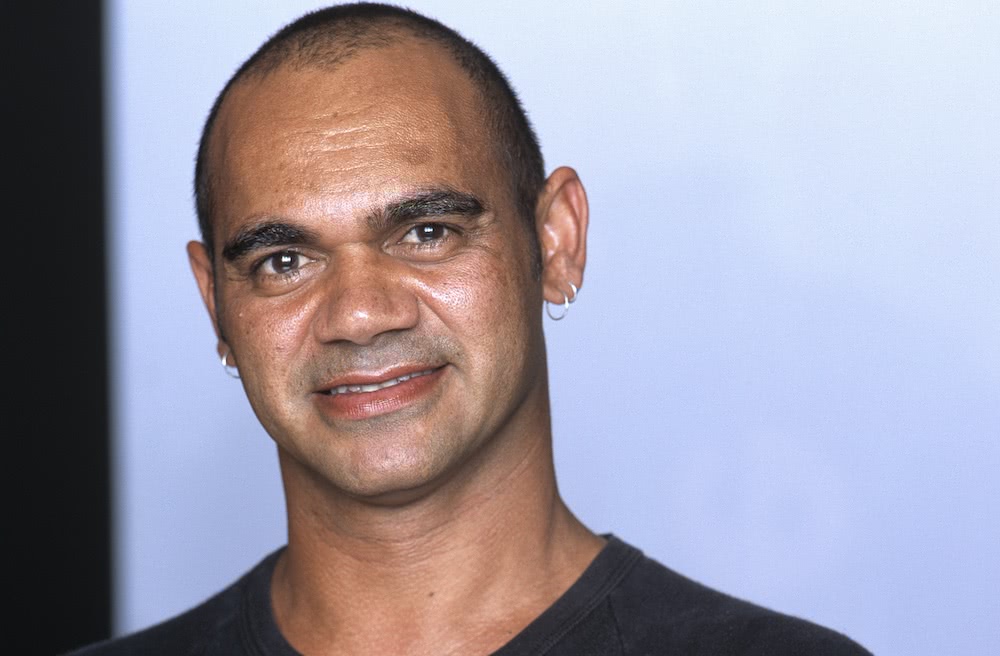

Over two years ago now, Australia lost the one-of-a-kind, dynamic, and respected musical composer, David Page. A descendent of the Nunukul people and the Munaldjali clan of the Yugambeh Nation, he was dedicated to preserving Indigenous tradition through sound and dance. With the help of Bangarra Dance Theatre, he presented Australian histories as told from First Nation peoples across the country.

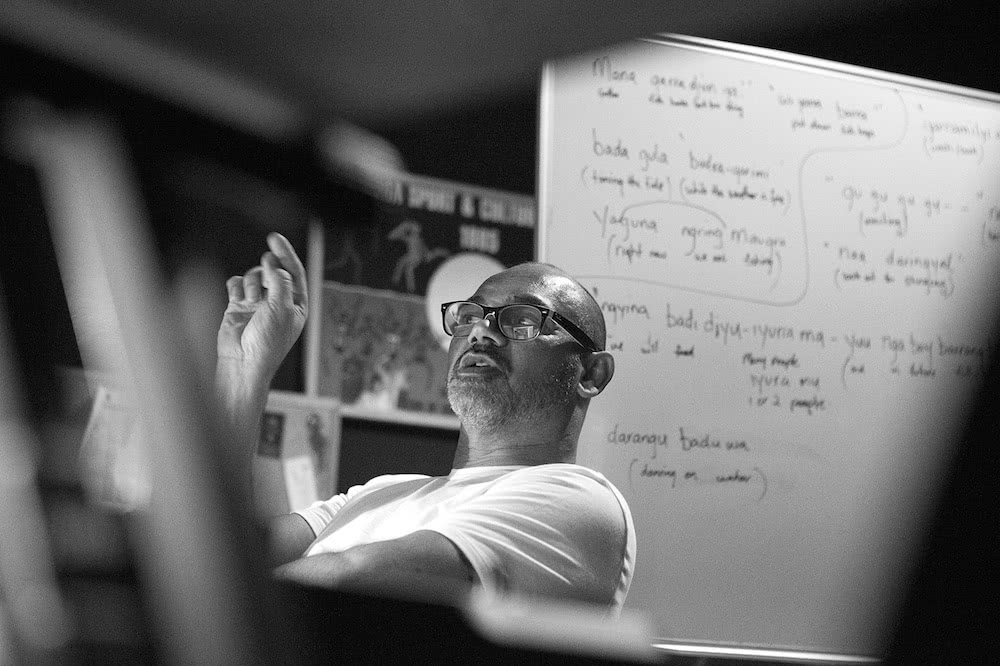

And now, his brother Stephen Page, the centre’s artistic director since 1991, plans to celebrate David’s legacy with the two-part performance series Dubboo – Life Of A Songman. “I bloody-well better get it right, otherwise he’ll be haunting me for the rest of my life,” jokes Stephen over the phone.

The two brothers were incredibly close, having worked on at least 25 productions with Bangarra. “I really, really, really miss the beautiful creative relationship we had – and I don’t think I’ll ever have that again with another person,” Stephen says.

They were two minds moving in tandem: Stephen was headstrong and direct; David was cheekier, a peacemaker. “He was mischievous, he was naughty. He always put a smile on my face,” says Stephen. “He’d always write these crazy melodies and lyrics. He tried out for the Bangarra competition, and I was like, ‘I don’t think that’s gonna work for contemporary sounds.’ And he would be a little bugga sometimes, he’d always sneak some in.”

Born in Brisbane, David was the eighth of 12 children. “We had a crazy upbringing you know,” says Stephen. He remembers growing up in inner suburbia; there’d often have big family gatherings – “always chaos…” he remembers – with the odd DIY variety show. “We’d dance and there’d be a lot of sharing of stories,” he says. He remembers David putting on his own floorshow. “He’d dress up and come down and do Bette Midler or Aretha Franklin.”

When David was just entering teenhood, he won a talent quest at the Sunnybank Hotel in Brisbane. And after seeing him perform, Warner Music Australasia’s Harry Geran signed him to Motown label, Atlantic Records – he was the first Australian to sign to the label. “At the time my parents knew nothing about the business or industry,” says Stephen. “[They were focused on] putting food on the table and a roof over our heads.”

He became known as Little Davey Page, releasing hit singles like the doo-wop, slow-dance ‘Dream Time Lover’ in 1976. Many saw him as Australia’s answer to Michael Jackson. Although, his pop star career was cut short when his voice broke at 15.

However, his pop spirit never ran dry. “In a way I think I should have pushed him more into that,” says Stephen of David’s affinity for musicals and more commercial outlets. “But he loved the challenge of composing what the land would sound like of places he went to, and how that would work with the traditional stories being told, and which instruments were going to complement that … There’s nothing more that he loved than that,” he explains.

“He wasn’t just a retired pop star. He was probably the only one working in this medium of traditional and contemporary music the score for dance theatre,” says Stephen.

The first half of Dubboo will see compositions with a string quartet, featuring songwriters and vocalists that worked with David over the years. “Iain Grandage has been a great help because he’s been doing the musical directing of a string quartet, and he’s been trying out listening to David’s songs and responding to them,” says Stephen.

Archie Roach, who worked with David on Bangarra’s 2000 production Skin, will perform, as well as long-time collaborator Ursula Yovich and member of the Munyarryun clan of northeast Arnhem Land, Djakapurra Munyarryun. “He’s very instrumental in terms of his traditional language,” says Stephen.

The second half will be a variety performance led by performer Ben Graetz as his alter-ego Miss Ellaneous. “David loved the performance side, and the cabaret side, and the variety side of things,” explains Stephen. “So the second half is just collating some of his favourite songs, so there is more of a variety response to that, using excerpts from when he told stories in Page-8.”

Bangarra takes its performances to venues as diverse as the Sydney Opera House to smaller rural communities all over Australia. “I think for us its just constantly keeping our cultural stories from a black perspective,” Stephen says of how the theatre aspires to instigate social change, which is one of the mission statements listed on their website.

For example, Bangarra’s recent work Dark Emu was designed as a response to Bruce Pascoe’s book Black Seeds: Agriculture Or Accident? Pascoe, a Bunurong man, used the records and diaries of Australian colonisers to prove that Indigenous peoples were cultivating the land – sowing, harvesting, irrigating – effectively challenging the hunter-gatherer stereotype.

“Last year there were close to 50,000 people who saw Dark Emu. So we are shifting people’s consciousness; we are educating people through the spirit of our culture, and that spirituality lies with dance and stories,” he says. “So if that’s prompted from a black perspective on social issues then it’s coming from our voice. That’s what we mean: hopefully we’re just re-educating the landscape in a different way.”

When Stephen was in school, he was suspended for questioning why Indigenous history wasn’t being taught. “[Your education] doesn’t tell some of the historical moments in this country – we don’t talk about the assimilating people to this country and the First Nations and the settlement,” he says. “We went to Berlin a couple of years ago; we sold out five shows in a 2000-capacity venue, and,” – he uses World War II as an example of addressing guilt – “the Germans have dealt with their guilt – they get on with it, you know.

“And you’re constantly debating the constitution. First Nations always [have to] take a back seat, and over here we’re discussing another Australia Day again. It’s just really embarrassing. We have a black history and so I think for Bangarra we feel that it’s about the resilience,” he says.

We discuss this resilience and the ways white Australia fails its Indigenous peoples: from higher rates of imprisonment and detention, to rural communities being left behind in government policies. “And we can’t even put in a senior Indigenous person to look after that. You’ve got to get someone like an ex-minister to be your Indigenous Affairs Officer. We can’t even make our own decisions. The respect of elders, and leadership, and knowledge of the land… Yeah, it’s very shameful,” he says.

“And look, putting that aside, you have the whole drought system, and the whole farming [situation]. It’s very much knowledge about the land that Indigenous people know that we didn’t take from and share,” he says.

Stephen is one of Australia’s longest running artistic directors with 27 years under his belt – and next year, the theatre responsible for teaching Australia’s Indigenous history will enter its thirtieth year of practice. “30 years compared to 65,000 years [of history] is just nothing,” he says of the stories waiting to be told. “You’ll have to be there for 100 years before you do any good damage.”

Asked how he feels about being in the role for so long, he explains that the thought doesn’t so much as cross his mind. “I just think about what’s ahead, how to reflect the past, be in the present,” says Stephen. “And to make sure that that learning and that hunger for knowledge and caring is around for the next generation for the future.”