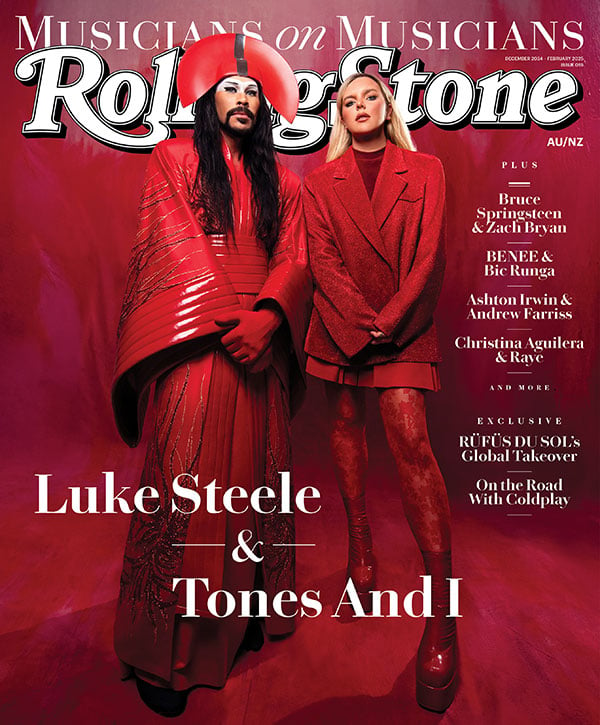

Australian writer, journalist and musician Nathan Jolly‘s debut book,Sydney Is For Strangers, is out now. It’s a seriesof interlocking stories about life, loneliness, and searching for love in the big city we call home, and you can read an excerpt below.

Illustration: Keiren Jolly

–

We are at a house party, walking from room to room, while Charlotte points out the tiny signs that the host is a functional junkie. Things that only someone who had been a drug addict before would ever notice: slightly bent paperclips; odd items in rooms they should have no occasion to visit; snowflakes of ash on bookcases; slight burn marks on pillowcases; the Lost In Translation soundtrack perched on the stereo…

Charlotte was once a drug addict and is now a drug user because even bread has habit-forming qualities and is probably killing us just as quickly. She was right about soy snacks, about plastic and fake sugar and Susan and Mickey, and she swears she is right about this, too—so I believe everything she says. Charlotte fell asleep on her arm two nights in a row, and it scared her enough to slide slightly straighter. We split up weeks after that, and neither of us argued hard that this wasn’t the main reason.

This kitchen is immaculate, which Charlotte notices and now I notice, and she assures me this also means something, and I nod, and she smiles, and we wonder how firmly we need to ingratiate ourselves with the host before we can change the CD. I like when house parties have CDs rather than computers, and I like when they have punch, too, because we all learned early from the same ten TV shows that punch equals party and therefore this is a common bond we share with every single host who serves punch—even if she is a closet junkie who spends hours manically cleaning and organising her fridge by food group. Charlotte tells me you can instantly tell a house party will be filled with terrible people if there isn’t a bookcase and a stereo in a common room. We argue for a bit about how books are often kept in bedrooms, especially in share houses, before Charlotte points out there should be more books than bedroom storage, especially in a share house.

This presents another wrinkle: does the overflow mean the books in the common room are an accurate representation of tastes—three people’s least precious reads—or a greatest hits collection, a boast which vastly overstates each individual’s true tastes, making the more-interesting seem less, and the less more? We can’t decide. I helpfully point to a cracked tile, but it doesn’t mean anything apparently—sometimes tiles crack.

The living room is filled with people I will never know. The stereo is loud and muffled, like it has been ordered to shout but is embarrassed by what it has to say. I take this music as a personal attack on me, but Charlotte sees it as a shortcut, the way she has seen most human behaviour ever since she changed majors from economics to sociology then back again. Charlotte never finished her degree and her mother still doesn’t know. She has never needed it, and come to think of it, neither have I. “I need a T-shirt with a photo of Yoko on” she says lazily, before collapsing into a cane chair.

Charlotte once told me the best time to interact with society while being on drugs was before 9am, because everyone looks like a shaken mess that early in the morning anyway. It made me skip back over every morning spent with Charlotte to try to remember signs: to remember her eyes, her reaction time, her pale, speckled face. But Charlotte was always quicker and much smarter than me (than I?) and now her eyes are dancing because she caught me looking at them for too long; I realised I didn’t know what colour they were—or thought I didn’t—until I knew of course I did. She kisses me on the lips sharply, then slowly for a few seconds longer. I realise I’m now sitting in her lap, on a cane chair in a lounge room swimming with strangers, so I get up and walk with purpose towards the stereo, but am too scared to change the music.

There are piles of blankets near the door leading out to the back porch; the evening is stupidly cool for this time of year, and our host is kind in that pure-hearted way where she steps out future scenarios and makes sure she is prepared. I want to tell her that I’d noticed this but since she doesn’t know me, it can’t have anything resembling a positive effect, so I don’t. The punch looks a different, more troubling colour than it was when we first arrived, so I decide not to risk another dip in the bowl; communal anything is a nice idea but it runs a short race.

Charlotte’s friend Lucy is already asleep, her neck craned uncomfortably, and because the three of us had walked to the party together, we’d signed on to bring each other’s bodies home—especially because this house is across from the dark corner of the dog park where the floodlights die and no taxi dare roam. I grab a bunch of blankets and cover her, and try to find a cup clean enough to fill with water and sit near her. She flinches and grabs my face and whispers to “Charlotte” to “try to bang [me] tonight”, because “he is being so obvious”—I stay and stroke her hair until she either falls asleep or stops moving. I slide under her limp, coat-hanger arm, and head out into the yard to find Charlotte.

Past the fire and the five-stringed acoustic guitar, she is scrunched against the fence, her phone shining a light on her face. “I was trying to find you” she smiles, and puts her arms out, as if she needs me to drag her to her feet.

Sydney Is For Strangersis available now on paperback and Kindle via Amazon.