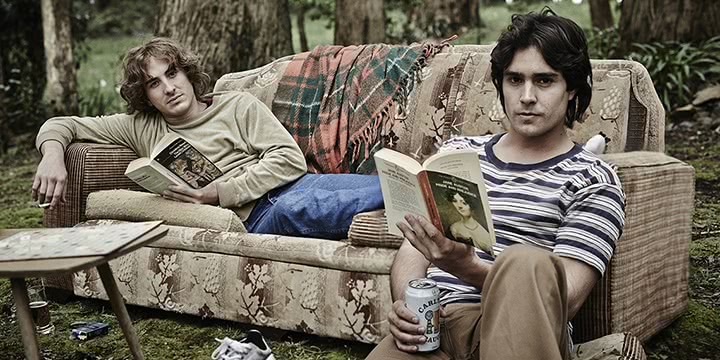

The thing that makes any film romance work, much like any real-life romance, is natural chemistry – an affinity with another that can’t be emulated. It’s precisely this aura that draws us to one another, keeps us burning with curiosity and fuels our passions.

I’m reminded of this as I sit in the AIDS Council of New South Wales office opposite Ryan Corr and Craig Stott, the leads in the Neil Armfield screen adaptation of Timothy Conigrave’s beloved memoir Holding The Man – particularly when I realise they’ve hardly taken their eyes off each other throughout our time together. They share such an easy camaraderie with each other that it makes them positively glow.

“That’s the sort of stuff you can’t act: it has to be there, and we had it sort of from the start of the audition process,” says Corr, mostly to Scott. “I remember looking up and going, ‘Wow, this guy’s looking at me, Ryan’ – you can really work towards creating fully grounded people if you’ve got that to start with.”

This magnetism alone, of course, wouldn’t be enough to sell the heady romance between Conigrave and his paramour John Caleo, the sadly deceased lovers on whom the biography is based. The intimacy Corr and Stott share on screen took months of work in order to make their affections read as genuine.

“We went to the bank as a couple, you know?” Stott says, grinning boyishly at his own recollections. “We’d go get lunch as a couple, holding hands –”

“We’d go to family dinners,” interrupts Corr, making Stott laugh.

“Ryan invited me as his plus-one to a family dinner,” Stott explains. “No-one had seen him in a while and he walked in holding my hand and –”

“I’d had an ex-relationship six months ago and we just came in as a new couple,” laughs Corr.

“Copped a few eyeballs that night,” says Stott.

This is likely to become a more common occurrence in their lives after Holding The Man hits Aussie screens – it’s a potent, paradigm-shifting kind of film with an inbuilt audience of devotees to Conigrave’s memoir. Corr shrugs off the ‘pressure’ of living up to both Conigrave’s book and screenwriter Tommy Murphy’s award-winning play. “In the end, we’re doing our job and we had each other to rely on. I mean, at least for myself, when I sorta got neurotic or worried, I had Craig to come back and rely on.”

“The fact that we developed such a strong relationship was the benchmark,” says Stott, attributing much of their success to the safety of the rehearsal environment created by Armfield. “It was conducive to learning and exploring, and there was never any talk about, ‘Oh, you’ve gotta do this and you’ve gotta do that.’”

That safety is vital for a film so uniquely physical, too – the film’s open sexuality and frequent nudity meant that Corr and Stott’s ‘getting to know you’ work was just the tip of the iceberg.

“He touched me – it was horrible!” Stott cries, making Corr laugh. “In terms of the sex scenes – honestly, it gets beaten around all the time, but it’s just another scene, you know?” he continues. “Except your balls and dick are wrapped up in a sock and you’ve got masking tape in your pubes.”

“It’s like a giant Band-Aid – Craig first came out, it looked like he was wearing a cabbage,” laughs Corr. “You can’t help but laugh at those sorts of things, at the absurdity. My first day on set was sorta like, ‘Hi Andrew, hi such-and-such, so we’ll be coating each other in baby oil and I’ll be biting your nipple, do you mind if I top you today?’ And the absurdity of that is never lost on anyone.”

Particularly not on Armfield, it seems. “There was one day I remember,” Corr says, “we came in, we’re like rehearsing one of the intimate scenes – I don’t remember – and he’s like, ‘OK, pants off!’

“You need trust, you need to innately trust each other, and I think that what Craig and I focused on most was developing a trust, and then… I pretended to like him,” Corr grins.

“I consider Ryan one of my mates – I’m always gonna look out for him, you know what I mean? That doesn’t just stop because the job is over,” says Stott.

Corr finishes his sentence: “We’re not playing pretend anymore.”

And they hardly were to begin with – as Conigrave and Caleo’s families are their living legacies, the rehearsal process had to focus on recreating them accurately.

“You find the essence of who these boys were,” says Corr, “and we had all these hands on deck to try and help us do that. And, you know, ultimately coming out and having Tim’s family come out and say ‘thank you’, or giving us their blessing – that was our job done.

“Scripts like this, stories like this, come along very, very rarely – if we’ll ever see one again – and I think we sorta felt like it was a blessing to be a part of this story.”

And what a timely story it is – with the marriage equality movement racking up a victory in the United States but pushed back by the Coalition government here, Holding The Man could not be more relevant.

“I think very rarely governments actually represent their people,” says Stott, “and there’s a broad consensus in Australia – 72 per cent of the population support gay marriage according to the Crosby poll … it’s coming out in an environment where people are open to equality. Unfortunately, our leaders aren’t, and they’re perhaps the ones that need an education. Love is love.”

“Love doesn’t discriminate,” says Corr, a sentiment Stott echoes.

“People discriminate, but love doesn’t. It transcends politics, it transcends Parliament House, it transcends senators, all of that shit, and hopefully one day our politicians will catch up with it.”

Holding The Man (dir. Neil Armfield) is in cinemas Thursday August 27.